Chapter Four: Where the Wild Things Are: Humans, Animals, and Children

Where the Wild Things Are

And let’s not forget the wolves. I insist on the forgetting as much as on the wolves and the genelycology because what we should not stint on here [foire l’iconomie de] is the economy of forgetting as repression, and some logic of the political unconscious which busies itself around all these proliferating productions and all these chasings after, panting after so many animal monsters, fantastic beasts, chimeras, and centaurs that the point, in chasing them, is to cause them to flee, to forget them, repress them, of course, but also (and it is not simply the contrary), on the contrary, to capture them, domesticate them, humanize them, anthropomorphize them, tame them, cultivate them, park them, which is possible only by animalizing man and letting so many symptoms show up on the surface of political and politological discourse. — Jacques Derrida, The Beast and the Sovereign

And let’s not forget the wolves. In Where the Wild Things Are, a beautiful and seductive story of childhood rebellion and exploration, the child-animal-wild continuum names a set of relations that cordon off the home from the world, that situate love alongside violence, and that link mobility to freedom and sequestering to ruination. Sendak introduces us to world threatened by a catastrophic conflict between mother and child, burdened by the phallic power of the absent father, and soaking in the child’s inevitable encounter with rejection and departure.

The child in this story, Max, may not have been raised by wolves, but he is, at any rate, wearing a wolf suit and making enough mischief that his mother calls him a “wild thing.” In response to his mother, and while embracing his wildness, Max says “I’ll eat you up.” For his punishment, Max is sent to bed without supper, and as he stands in his room, alone and hungry, a world grows around him and then an ocean and then a boat, and he sails off, “in and out of weeks,” until he arrives “where the wild things are.” The wild things, part human and part animal, “roared their terrible roars and gnashed their terrible teeth and rolled their terrible eyes and showed their terrible claws.” When the wild beasts see that Max is not afraid of them, and when he tells the creatures to “be still!,” the wild things make Max their king and celebrate with a wild rumpus. Eventually Max gets sick of being king and “the most wild thing of all”; he is lonely and wants to be loved and fed. And so, home he goes, lured by the smell of his mother’s cooking, and he reenters the home, perhaps in the absence of any other truly wild space to go.

Sendak, who died in 2012 at the age of eighty-three, was the child of Jewish-Polish immigrant parents who moved to Brooklyn in the 1920s; he was also gay. Indeed, queerness limns Where the Wild Things Are and resides within the implicit critique of the family and in the marginalized spaces to which the wild things have been banished. Publication of the book certainly raised concerns for some parents, and initially it was excluded from some libraries in 1963 despite being very well received (the book won the Caldecott Medal in 1964). The grotesque figures that make up the world of the wild, and the anger that propels the small protagonist to join them, along with the implication that there are worlds of rejected people just beyond the space of the domestic, go some way toward identifying both the disturbing quality of the book and the queerness that underlines its narrative. Max’s status, in his wolf costume, as half boy – half animal, as partially wild, confirms the unsettled arrangement of desire and embodiment that might constitute the precondition for queerness. Wildness, in this book, sometimes functions as a synonym for queerness, but at other times it names a mode of being that lies outside of the systems of classification that nest human bodies into clear and nonoverlapping categories. Wildness names the potential of certain forms of desire to stray beyond the boundaries of family and home. For this reason, Sendak’s gayness, while not an explicit part of his storytelling, props up the human-animal-child dynamics in much of his work that are notable for their eccentricity.

Photo by Егор Камелев on Unsplash

Sendak’s Jewishness also played a role in his conjuring of the wild. Sendak saw childhood not as an experience of “sweetness and light,” but as a dark experience of anger and rage as well as cruelty. Sendak supposedly modeled his wild beasts on his older Jewish relatives who, according to him, were unpredictable and a little threatening because they were always offering to “eat you up.” In an interview with the Guardian published in 2011, Sendak told the journalist, “The monsters from Wild Things were based on his own relatives. They would visit his house in Brooklyn when he was growing up (‘All crazy — crazy faces and wild eyes’) and pinch his cheeks until they were red. Looking back, he sees how desperate they all were, these first-generation immigrants from Poland, with no English, no education and, although they didn’t know it in 1930, a family back home facing extinction in the concentration camps.” The article continues: “Sendak’s picture books acknowledge the terrors of childhood, how vicious and lonely it can be.” Sendak, who understood himself as a lonely child of desperate parents, never tried to soften the edges on life for his child readers, and they loved him for it. He never apologized for the menace his story presented, a menace that emerged from the intimate space of the family itself. Sendak refused the sentimentality that shrouds so much of children’s literature and offered his small antiheroes up to the darkness, to the monsters, to the wild.

Max, meanwhile, after a day of being bad and all dressed up in his wolf suit, inspires his mother’s wrath. She calls him a “wild thing,” to which he responds by saying “I’ll eat you up!,” and “so he was sent to bed without eating anything.” In his bedroom that fateful night, as he lay estranged from his mother, at odds with the world, wild in his aloneness, a new world grows around him — first a forest sprouts, the vines hang from the ceiling, and finally “the walls became the world around.” When an “ocean tumbled by with a private boat for Max,” he sets sail across time and space until he arrives where the wild things are. The wild things do their wild thing routines — “they roared their terrible roars and gnashed their terrible teeth and rolled their terrible eyes and showed their terrible claws.” The repetition of “terrible” here magnifies the threat that the monsters perform and partakes in a state that Adriana Caverero names as part of “horrorism.” Horrorism, for Caverero, describes modern violence that numbs the human, stills it, undoes it. But more than this, horrorism is violence that issues from the very people and institutions that claim to protect. Offering the mother as an obvious example of a figure who can either care for the child or destroy it, Caverero proposes that care and harm are nestled within the same social function. The monsters Max encounters, then, are the unleashed creatures of the maternal unconscious, the beasts who represent the mother’s deep ambivalence toward the child — shall I eat it or let it eat? Shall I kill it, silence it, or help it to thrive? But Max has his own magic trick and rather than be stilled by the wild things he tames them by returning the gaze and “staring into all their yellow eyes without blinking once.” The child’s gaze is terrifying in its unwavering and all-seeing control. He knows he must still or be stilled, see or be seen, rule or be ruled, eat or be eaten. And so, in this Hobbesian state of nature, in a world of violence and wildness, Max does the only thing possible as child sovereign. He calls for a riot, he authorizes confusion and disorder, he indulges his orientation to chaos. “And now,” cries Max, “let the wild rumpus start!”

In one domestic space, the home, the child performs wildness in response to an adult; and in the realm of the wild things, Max presides over the wild things who threaten, in response, to eat him up. And because he shuttles between the order of the oedipal household, where his mother rules, and the ruined world of the wild, where no one is in charge but him, he knows the parameters of the real — he sees that either you settle in to the domestic prison you have been offered or you set sail for another, potentially more violent, terrain. The wild here is not a place and not an identity; it is neither sanctuary nor utopia. The wild is not heaven, hell, or anything in between; the wild is the space that the child and adult share in their antipathy to one another. The wild is entropic, cruel, and violent; it is, in the words of T. S. Eliot in “East Coker,” “the way of dispossession” in which “in order to arrive at what you are not / You must go through the way in which you are not. / And what you do not know is the only thing you know / And what you own is what you do not own / And where you are is where you are not.” Eliot and Sendak are saying something similar here — they both recognize that only the “movement of darkness on darkness” can lead to knowledge; only in the wild rumpus can monsters recognize each other; only in negation can the child know that it must represent and fail to represent innocence. When the mapping of innocence onto the child fails, indeed, and the failure is inevitable, we speak of the child as wild and monstrous.

In the context of Sendak’s children’s book, the child is never made to shoulder the burden of innocence. Here, he knows what is expected and refuses to perform. And so, in the story, the wild is a shifting landscape that depends on an odd geometry of human, child, and animal arrangements. When the child is king, adults are ruined; where adults are wild, children cohabit uneasily and precariously with them; where children are wild, adults enforce rules and regulations. Wildness, in other words, is a set of relations, a constellation really, within which bodies take up roles and scripts in relation to one another. At home, Max is the wild thing because he defies his mother and because he issues the cannibalistic threat to “eat her up.” Far from home, Max is not wild because he meets the creatures who are; these wild things are survivors, ruined adults who have been cast out of the space of the domestic and the tame and who have found the violence of the wild preferable to the violence of the domestic.

Like an embodiment of the amoral, the wild things stand in opposition to what Nietzsche calls the “disgrace” of the domesticated human who must use morality and clichés to cover over their true feelings of anger, outrage, disappointment, and fear. This tension between the wild side of human nature and the civilized or domesticated side comes to the surface in book 5 of The Gay Science, where Nietzsche writes:

Now consider the way “moral man” is dressed up, how he is veiled behind moral formulas and concepts of decency — the way our actions are benevolently concealed by the concepts of duty, virtue, sense of community, honorableness, self-denial — should the reasons for all this not be equally good? I am not suggesting that all this is meant to mask human malice and villainy — the wild animal in us; my idea is, on the contrary, that it is precisely as tame animals that we are a shameful sight and in need of the moral disguise, that the “inner man” in Europe is not by a long shot bad enough to show himself without shame (or to be beautiful). The European disguises himself with morality because he has become a sick, sickly, crippled animal that has good reasons for being “tame”; for he is almost an abortion, scarce half made up, weak, awkward.

Even allowing for the instability of translation, this is an outrageous passage and one that contributes to the readings of Nietzsche as invested in a model of superior and inferior beings. But, actually, Nietzsche, like Freud, is trying to poke at and challenge the moral order requiring that man, however wild he may be, perform his goodness in quotidian interactions. Conventional wisdom opposes the wild to the tame in terms of a wildness that must be dressed up and covered, suppressed and denied. But for Nietzsche, the wild animal in European man represents an order of being that does not require the alibi of morality to cover over his violent orientation to the rest of the world. The “tame” here is the name for the vexed relation between goodness and exploitative violence that continues to define dominance. Lashing out at “the herd animal,” Nietzsche fears not the predator, but the prey: “It is not the ferocity of the beast of prey that requires a moral disguise but the herd animal with its profound mediocrity, timidity, and boredom with itself” (295). Nietzsche depicts this herd animal in terms that connect disability — “sick, sickly, crippled” — to the status of the nonhuman — “animal” — and both to the liminality of the “abortion” (295). In this way, Nietzsche’s own logic doubles back on itself and reinvests in the very binary of wild/tame that he seems to want to question. While we might see value in critiquing the herd animal or the prey for its “mediocrity,” and while we might want to see a potentially decolonial violence unleashed in the figure of the predator, the ableist characterization of the tame human as also “crippled” reinvests in a colonial power sequence and, perhaps, declaws the critique of domestication that Nietzsche offers.

The Nietzschean “things” that Max meets are wild because they can never go home, because they no longer believe in the falsehoods of family and community, and because they refuse to disguise their wildness, their ruination, and their place in a violent order of things. The wild things are not dressing for conquest, Doujak might say. They are naked, exposed, committed neither to covering up their wildness nor to performing civility. They are wild, they are angry, and they will not be tamed. What was understood to be disturbing about Sendak’s book in the years after it was published, however, has changed over time. In the late 1960s, Bruno Bettelheim critiqued Where the Wild Things Are in Ladies’ Home Journal. Bettelheim claimed that Sendak’s book played upon a child’s fear of being abandoned by one’s mother. And, a critic for Publisher’s Weekly worried that “the plan and technique of the illustrations are superb. … But they may well prove frightening, accompanied as they are by a pointless and confusing story.” Child readers did not find the story pointless, reminding us that children read differently and see the relation between image and text with different eyes, and while some children may have found the book frightening, it has been experienced by millions of children as a book that delivers a pleasurable thrill. Sendak responded to criticism of his work in The Art of Maurice Sendak, in which he was quoted as saying, “I wanted my wild things to be frightening.”

Some forty years after its original publication, Sendak’s beloved book was turned into a film of the same name by Spike Jonze (2009). In this film version, a different kind of threat emerges. If the original book made some people worry about a tale of abandonment, the film draws out the sadness and melancholia of the wild and those who live there. In an odd, family-unfriendly film peopled with puppets and humans, Jonze was able to convey the weightiness and the burden of wildness. For a start, the puppet heads worn by the puppeteers in the film, and created by the Jim Hensen Company of Muppets fame, were literally too heavy and required some careful balancing by the puppeteers who wore them. Eventually the scenes with the puppet heads were reshot using cgi. Second, Warner Bros. was not happy with how bleak the film was and wanted Jonze to reshoot; however, Jonze insisted on sticking to the mood he had established for the characters and Max and sacrificed high-volume audiences by refusing to make the film into just another adorable kids movie with a clear moral frame. Finally, the decision to use puppets rather than animate the wild things surely contributed to the film’s conjuring of a level of discomfort for the viewer. Sendak refused to sanction an animated version because he felt that animation would make the wild things cute and Max adorable, and the whole wild rumpus would lose its menacing edge.

Ultimately in Where the Wild Things Are, the wild, despite the promise of the title, is not a destination, and nor is it an identity. Rather the wild is the un/place where the people who are left outside of domesticity reside — small children, animals, and ruined adults, an anticommunity of wildness. We find survivors, humans who have lost all belief in the concept of humanity as something noble, empathetic, and uplifting and for whom concepts like order, civilization, goodness, and right mean nothing and fail to provide the protection they imply. For the wild things, the violence of the world has been revealed, and nothing can ever be the same. The connection between Max and these survivors is their unvarnished view of the world, their understanding that the world is brutal and violent and that it will eat you if you do not threaten to eat it. These fantasies of incorporation, moreover, are both fantasies of power and recognitions of the way that power works incorporatively, vertiginously even; power is not something to have or to wield, Max learns the hard way, it is something that will swallow you whole, absorb you into its organic system. The “thing” in “wild things” surely distances being from subjecthood and conveys an object like status to the bodies of those who are ruled and rejected.

* * *

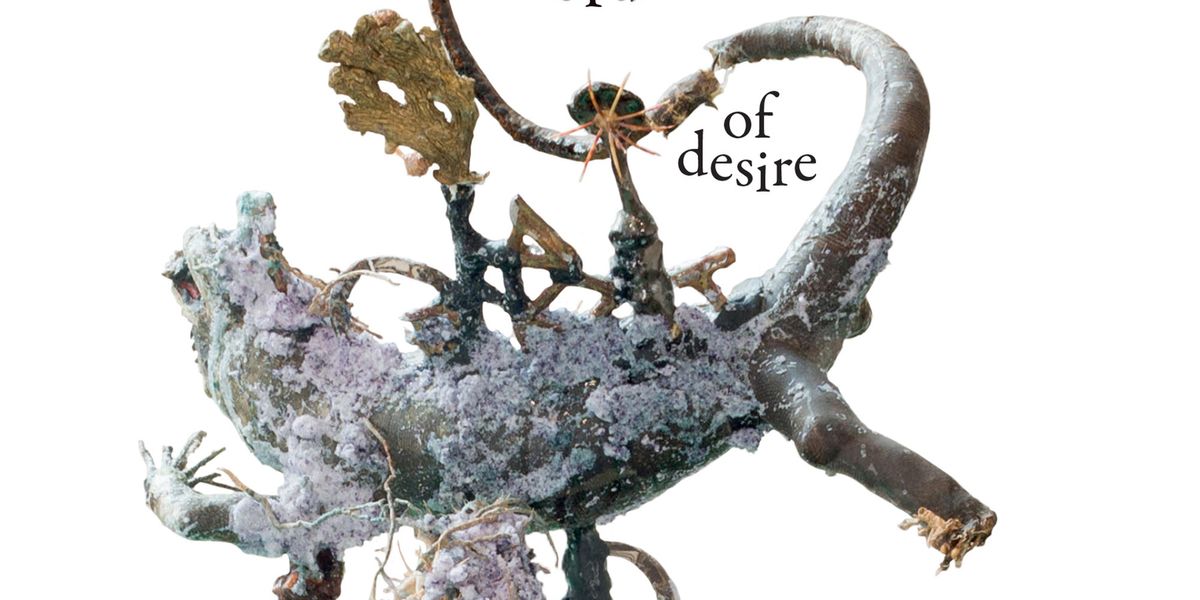

Reprinted with permission from Wild Things: The Disorder of Desire by Jack Halberstam, published by Duke University Press (footnotes omitted). © 2020 Duke University Press. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.