Then and now, the mighty Led Zeppelin towers imposingly as one of rock’s elite groups. The source of at minimum four must-own LPs, dozens of classic rock radio staples, and enough legendary guitar riffs to make Keith Richards look like a slacker — not to mention being the inspiration for entire genres, from glam metal to grunge to stoner rock — it could be argued that the British quartet is just one notch below the Beatles in the rock hierarchy, and is an entity that defined the 1970s as much as the Fab Four defined the preceding decade.

Led by guitarist Jimmy Page, the assured, larger-than-life Zeppelin blended hard-edged British Invasion guitar riffage, heady post-psychedelia, and Mississippi Delta blues together in a manner, when amped up to the sonic extremes the technology of the day would allow, resulted in the style the world would come to know as heavy metal. For that alone the band earns a hallowed place in musical lore. However, Zeppelin always refused to restrict itself to bludgeoning caveman headbangers (something which would result in metal fans often positioning Black Sabbath — an ensemble that is on record as being enamored by and taking cues from Zep — as the “proper” founding father of metal), instead maintaining a broad stylistic palette that incorporated acoustic instruments and diverse ethnic sounds to realize the “light and shade” dynamics Page strove for.

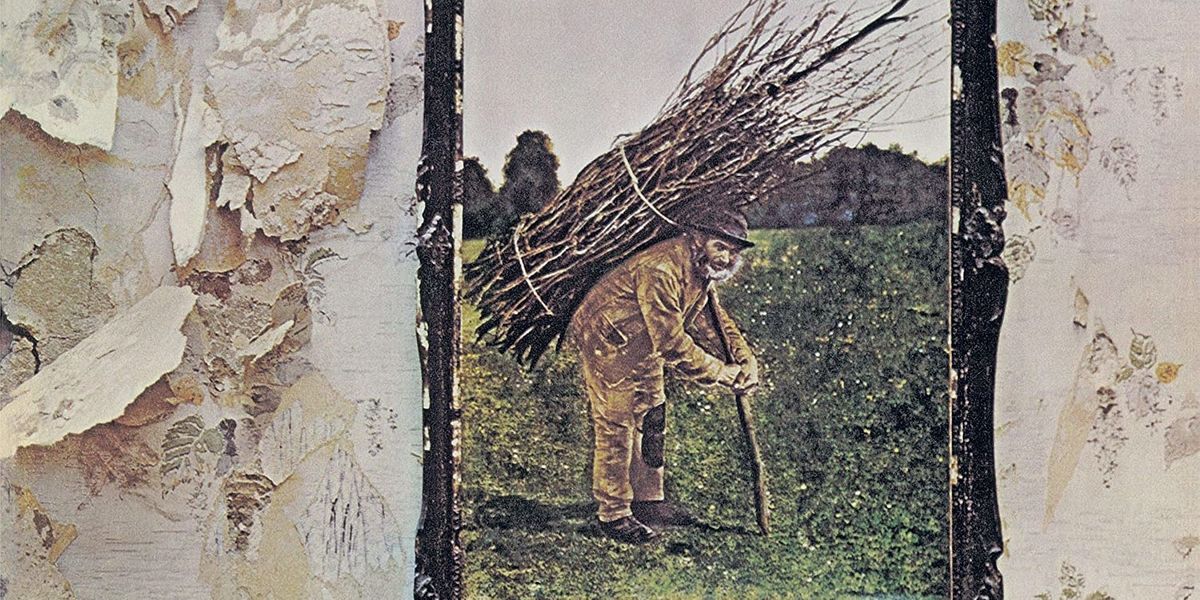

Nowhere is Led Zeppelin’s carefully balanced blend of eardrum-bursting heavy rock and delicate folk strains better realized than on its untitled fourth album, an LP that has become one of the biggest-selling and most-disseminated albums of all time, in any genre. Issued without a name or any identifying details on the sleeve in a pointed attempt to let the music speak for itself amid press accusations that the band’s fortunes were the result of hype, the record is most commonly labeled as Led Zeppelin IV in reference to numbered titles of the first three Zep full-lengths (for the sake of clarity, it will be referred to by that name for the purposes of this series); it has also been afforded monikers including Four Symbols, Runes, and ZoSo due to the mysterious icons representing each band member that adorn the record’s packaging.

Though worldwide sales figures for any record are tricky to verify, in 2007 The Independent cited the fourth Zep LP as selling 37 million copies globally, an amount that has few plausible challengers. National figures are much more reliable: in the United States, the album is certified 23 times platinum by the RIAA for that many millions of copies shipped, making it the fourth most-abundant LP in the country, below only works by Michael Jackson, the Eagles, and Pink Floyd. This album isn’t just a blockbuster; it’s an essential text in popular music; a rite of passage for budding guitarists and suburban stoners; a record that with every single one of its eight cuts being perennials on rock radio playlists it’s nigh-unfathomable to imagine one not having an opinion on it, be it favorable or dismissive. If you are a diehard rock music fan who’s gone his or her life without hearing Led Zeppelin IV, I can quite justifiably demand to know what the hell your problem is.

The stature of Led Zeppelin IV is astounding to consider, especially since its sales outstrip those of not only virtually any other record in existence, but anything else in Zep’s discography by at least 2-to-1. The inclusion of “Stairway to Heaven”, the insanely-overplayed FM radio epic that is an eternal candidate in the “greatest song of all time” sweepstakes, is certainly a factor that helps explain the LP’s massive popularity. Further legitimizing its success is the collective strength of every other composition on the album, the end result outshining everything other full-length the band issued.

Never a group to waste material on b-sides, Zeppelin assembled its wares with deft precision and loaded them with bountiful heaps of indelible guitar licks, drum fills, and sex-charged wails that ended up inspiring several successive generations of artists (and continue to do so). One can spend ages pouring over every little musical nuance of Led Zeppelin IV, and the mysteries surrounding its quixotic packaging (who is the man on the cover and the hermit in the fold-out poster, and what exactly do those runes represent?) and the debated influence of black magick stemming from Page’s sizable interest in the occult (Black Sabbath more often than not cautioned against dealing with dark forces; Zeppelin reveled in them) only add to its mesmerizing appeal.

Led Zeppelin, Musikhalle Hamburg, März 1973.

Photo: Heinrich Klaffs – originally posted to Flickr as Led Zeppelin 2203730017 / Wikimedia Commons / CC BY-SA 2.0

1.”Black Dog”

An album as weighty as Led Zeppelin IV warrants a brash, ear-grabbing opener, a criteria “Black Dog” ably fulfills. After a few seconds of incidental studio noise, the disembodied voice of Robert Plants pops out of nowhere, singing the couplet “Hey hey Mama, said the way you move / Gonna make you sweat, gonna make you groove”. Then BAM, Page, bassist John Paul Jones, and drummer John Bonham burst out with enough force and volume liable to lay the listener flat (as it did to this author the first time he heard it when he was just about 13 — it’s still one of the very few musical discoveries that genuinely blew my mind). It’s all undoubtedly, resolutely heavy, but there is also a finesse to the track that critics of the day often overlooked as it slated the group as being crass and excessive.

“Black Dog” is structured around a call-and-response routine (inspired by Fleetwood Mac’s “Oh Well”) that contrasts Plant’s a cappella come-ons against the band’s heavy metal riffage, where Page and Jones play the same notes an octave apart to create that massive sound. Written by Jones, the Muddy Waters-indebted “Black Dog” riff is a nimble five-bar work of ingenuity that tosses in a measure in 5/4 time instead of standard 4/4 for extra punch. Coupled with Bonham’s earth-shaking drum beats, the result is what’s been termed the “stomp groove”. As “Black Dog” proves, grooves aren’t only supposed to static or hypnotic; what ultimately defines a great groove is its ability to overwhelm the body and make it move in time with the music. “Black Dog” makes the listener twist and contort with its displaced beat accents, with the end result being fist-pumping or headbanging instead of busting a move.

About the only reasonable criticism that can be leveled at “Black Dog” is one that can be raised against Led Zeppelin on a broader level, and much ’70s rock as a whole. In an era when macho swagger and boasts of sexual prowess were seen as fundamental to rock iconography, Led Zep was a thoroughly masculine, alpha-male enterprise, often skirting the line of casual sexism as it regularly relegated women to the roles of pleasure props or witchy offenders both on and off-stage. In “Black Dog”, Plant is almost demonically possessed by lust (“Eyes that shine, burning red / Dreams of you all through my head”), but it quick with criticisms of the object of his desires (“I won’t know but I’ve been told / Big-legged woman ain’t got no soul”). Though Plant’s final verses of “Need a woman, gonna hold my hand / And tell me no lies, be a happy man” suggest a wounded sensitivity, the feline sensuality of his delivery betrays his true intentions — he’s kidding no one that he’s not just upset that a woman used him like he wanted to use her, especially given the way he orgasmically moans in the transition to the outro section.

With those sweaty, thrusting rhythms and Plant’s banshee cries, “Black Dog” is undoubtedly sex music. Yet it’s so accomplished that even if we can’t forgive Zep for thinking with its collective nether region, we can marvel at the awesome musicianship that ensures the composition continues to outshine much hard rock that has emerged in the 40 years since the public first heard it initiate the start of this band’s magnum opus. It’s easy to be heavy, but doing it with style is another matter entirely.

2.”Rock and Roll”

Not long after “Black Dog” fades into the ether on the Led Zeppelin IV tracklist does John Bonham come roaring back, making a tremendous racket on his drumkit to lead listeners into “Rock and Roll”, Zep’s ode to the genre’s golden age. The song emerged during a stalled attempt to record another track for the album; blowing off steam between takes, Bonham started playing the opening beat to Little Richard’s “Keep A’ Knockin'”, which Zeppelin guitarist Jimmy Page instantly augmented with a ’50s-style boogie riff that he wrote on the spot. Singer Robert Plant added to the time-warp fun by throwing in references to the Diamonds, the Drifters, and the Monotones in his lyrics.

Despite its origins, “Rock and Roll” is no by-the-numbers retrofest. The introductory drum part from “Keep A-Knockin'” is retained for the song, but in Bonham’s meaty mitts, the fill was transformed into the fitful starting rumble of a relentless steamroller that plows onward, with John Paul Jones gamely keeping pace as he pummels out his chugging eighth-note bassline. Coming in on an off-beat instead of right on the downbeat, Page’s riff swings and thrashes around, inevitably allowing for showy chord crashes that were suited to the arenas Led Zep would soon make its home in. Plant’s distinctive wail as always is unmistakable, his preening croon of the line “It’s been a long time since I rock and rolled” owning more to his rowdy blues inspirations than any Elvis Presley or Little Richard imitation.

Essentially, what Led Zeppelin did on “Rock and Roll” was what it did for the blues on previous LPs: amped it up to supersized proportions, imbuing the form it tackled with overwhelming brute force and a raging libido that could not be disguised by wordplay. It can actually be easy to overlook how closely Zep follows the ’50s rock ‘n’ roll template on the track since it sounds so quintessentially ’70s in its execution. Dial back the distortion, pull back the attack, and throw plenty of cold water on Plant, and the song’s grounding in comparatively-quaint early rock singles from 15 years prior becomes much more clearer.

Personally, though, I’ve never warmed up to “Rock and Roll” as a lot of others have (for starters, it was one of four Zeppelin tunes to make VH1’s “100 Greatest Songs of Rock & Roll” countdown in the late 1990s). To me, “Rock and Roll” has always felt like a means to keep the momentum inaugurated by “Black Dog” going rather than a proper song in its own right. Though every member of the band turns in a stellar performance from a technical standpoint, it’s the attitude that makes the track. By extension, that has always left me with the feeling that the group could have been dabbling in any other form at that point on the record as long as it was approaching it with similar gusto.

Regardless, it’s hard to quibble when a band such as Led Zep — at the height of its powers on this album — is clearly having a ball running through a beloved style that inspired its members during their formative years. That’s as good explanation as any as to why “Rock and Roll” is so highly regarded in the Zeppelin mythos.

3.”The Battle of Evermore”

Before you inevitably ask, let’s set the record straight: yes, this song is totally referencing J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings book series.

Tolkien’s fantasy trilogy had unexpectedly found an enthusiastic readership among the hippie generation, who were awed by the writer’s dense epic about ancient realms, hobbit-folk, and wise bearded mystics. And in spite of his strutting, sex-charged stage persona, Led Zeppelin vocalist Robert Plant was nothing if not a total Black Country hippie. Not only did Plant devour Tolkien’s tomes enthusiastically (a huge fan, he even named his dog Strider, after the alias the hero Aragorn assumes in the first Lord of the Rings book, The Fellowship of the Ring), but was also a history buff, delving into books about Celtic mythology and Middle Ages military history.

Plant’s favorite sections in the library make themselves apparent on the charging Celtic folk of “The Battle of Evermore”, one of the purest examples of the singer’s flowering as a lyricist on Led Zeppelin IV. The musical side of the song originated during a late night at Headley Grange, the old manor where Led Zeppelin IV was recorded, when guitarist Jimmy Page picked up one of bassist John Paul Jones’ stray mandolins to fiddle around with, leading to him and Plant writing the tune on the spot. Plant’s conception for the lyrics however originated back during songwriting sessions for Led Zeppelin III (1970), when he and Page where holed up in a cottage in the serene Welsh countryside to craft that largely-acoustic record.

Having been encouraged by Page to handle more of the lyric-writing himself, on “The Battle of Evermore” Plant eschews verses about loose women and his raging libido in favor of straight-up high fantasy, a topic that would soon become an overabundant heavy metal trope due in no small part to Led Zeppelin’s popularization of the subject matter. In the song, Plant is essentially describing the Battle of the Pelennor Fields from The Return of the King, name-checking Tolkien characters Aragorn (“The prince of peace”), Eowyn (“The queen of light”), and the villainous Sauron (“The dark lord”) and his fearsome Ringwraiths (who “ride in black”). This isn’t exactly Middle-Earth, though, as Plant also mentions the “angels of Avalon”, a distinct reference to Arthurian lore. Plant’s not really trying to painstakingly relate one particular event from lore; instead, Plant is smooshing his inspirations together to craft a mythic battle of his own that despite its late 20th century origins reads as if it was born eons earlier.

Plant and his group succeed admirably. Coupled with the lyrics, the naked acoustics of the mandolins and Celtic-tinged melodies of “The Battle of Evermore” result in a track that sounds positively legendary compared to the more modern, post-industrial society likes of “Black Dog” and “Rock and Roll”. The song’s slow fade-in at the start enhances the mood, as if the listener was learning of an ancient tale as it gradually became unobscured by the mists of time. There’s no percussion of any kind on the track, but Page maintains an urgent, rhythmic thrust in the way he plays the chiming chords of the mandolin–punctuated by sharp chord stabs at pivotal moments—that pushes the song continually forward, making the song as exciting and blood-pumping as any of Zeppelin’s heavy rockers.

“The Battle of Evermore” didn’t just spring from the ether with no direct precedent, though. Though the band’s debt to (or outright pilfering of, depending on who you talk to and which song is being discussed) the blues is common knowledge, what’s often overlooked in comparison is how much of an impact the vibrant British folk scene of the late 1960s and early 1970s had on the group, particularly Zeppelin favorites Bert Jansch, Roy Harper, and Fairport Convention. The folk influence was there from the start, functioning as the “light” that balanced out the heavy metal “shade” to create the nuanced stylistic constrains Page strove to maintain, but it was the unjustly underrated Led Zeppelin III that underlined its presence in Zeppelin’s sonic stew. Unfortunately, the negative fan reaction to that LP’s acoustic character meant that the band felt it had something to prove with its subsequent full-length, meaning in the greater context of Led Zeppelin IV tracklist “The Battle of Evermore” comes off as a strange yet thrilling non-rock detour after the full-on metal bombast of the first two cuts, instead of a logical full extension of a previously-established furrow that it actually was.

Zep’s affection for contemporary British folk is made even more tangible on record by the guest appearance of former Fairport Convention vocalist Sandy Denny on “The Battle of Evermore”, who acts a mournful counterpoint to Plant’s narration, functioning in Plant’s words as “the town crier urging people to throw down their weapons”. Denny more than ably complements Plant, matching him every step of the way as his delivery builds in intensity on the journey to the song’s climax (Denny mentioned in a 1973 interview that the session had left her “hoarse”, and added, “Having someone out-sing you is a horrible feeling . . .”). Denny’s voice is airy and angelic, almost otherworldly in its timeless timbre; it’s no wonder Led Zeppelin afforded Denny the honor of her very own rune, just like the ones each member of the group received on the album’s artwork.

4.”Stairway to Heaven”

I’ve been long amused by the acoustic cover of “Stairway to Heaven” the Foo Fighters performed on Later with Craig Kilborn a few years back. It’s a pretty entertaining take, certainly (love the guitar solo!). But what always strikes me most about that broadcast is how it only takes Dave Grohl a scant few notes of guitar-picking before the studio audience recognizes the tune and accordingly loses its mind. Furthermore, huge chunks of the crowd can recite the lyrics by memory to assist Grohl when he forgets the proper lines. That doesn’t happen with just any random tune.

The fourth track from Led Zeppelin’s fourth album isn’t any ordinary song — it’s an institution. I’m not talking about the eight-minute-long multi-act monster that is “Stairway to Heaven” merely being the blatant centerpiece of Led Zeppelin IV. It’s the only cut from the album to have its lyrics included in the packaging and the first effort from the group’s songbook to afford the honor of having its words appear in the liners. I’m talking about it striding confidently as Zeppelin’s signature song, the most-played track in the history of FM radio, and a rite of passage for any budding guitarist noodling around in his or her local music instrument store until some killjoy employee comes by to tell the poor kids that song is not allowed there. There’s a famous clip from Wayne’s World where the protagonist is shown a store sign that says “No Stairway to Heaven” after attempting the tune hits close to home for many musicians. A towering achievement that casts a massive shadow over rock music 40 years later that few dare challenge, “Stairway to Heaven” is nothing less than one of the greatest rock songs ever — possibly even the utmost finest, judging by a scan of critics’ lists and by informally polling the nearest group of classic rock-loving bros you can find.

Of course, there are those out there who are sick about the endless ravings that accompany Led Zeppelin’s magnum opus. With a song this revered and well-known, it’s only natural that given the millions who have heard it, even if a small minority of that number could go without ever listening to it again, the total would still be quite sizable. Think of anyone who hates hard rock or heavy metal, or those long-suffering Guitar Center employees who would be grateful if teenagers would just stop fumbling around with the song’s opening chords on the display guitars in their misguided attempts to look impressive. Whether someone has grown weary of Robert Plant singing about bustles in hedgerows for the zillionth time or never liked the sound of his voice, to begin with, not everyone is willing to bow at the altar of “Stairway”.

The constant charges of plagiarism that dog Zeppelin maestro Jimmy Page also follow his most beloved song, as critics over the years have pointed out the similarity between “Stairway”‘s acoustic introduction and the 1968 recording”Taurus” by the California band Spirit. Page was certainly aware of the group—the two ensembles toured together—and the similarity between the chord progressions is unmistakable. But it can be argued that the guitarist weaved his own distinctive melody for his composition. Does “Stairway”‘s resemblance to “Spirit” tarnish its majesty? I’ll leave that to you to decide.

The similarities between the songs do little to dampen the legend of “Stairway to Heaven”, as the power of the song really lies in its slow-burn climbing structure, not in its melody or lyrics. “Stairway” journeys gradually away from the folkish acoustic finger-picking that it begins with, garnering additional musicians and inching toward faster tempos until it climaxes with an incendiary heavy metal ending. The first big signpost is when Page switches from his acoustic to electric guitars around the 2:14 mark, with Plant musing “And it makes me wonder” as the transition takes place. The new chord progression that arrives when Plant sings “There’s a feeling I get” has an ascending quality that builds up anticipation for the listener.

At 4:19; drummer John Bonham makes his impeccably-placed introduction, finally nailing down the song’s groove to inch it ever more towards rock Valhalla. At 5:13, Bonham hits a cymbal crash to announce a chord figure that sounds like a fanfare announcing the arrival of the gods. In a way, it does: just before the six-minute mark, Page launches into The Solo, a stirring segment that on its own goes a long way towards maintaining the man’s place in all those “Greatest guitarists ever” polls. Bonham takes the opportunity to unleash some pummeling fills, and then for the last minute or so we are treated to the full-on rock-out section, with Page strumming barre chords on his electric guitars, Plant screaming at the top of lungs, John Paul Jones playing melodic riffs on his bass, and John Bonham pounding the ever-loving hell out of his drumkit. When the maelstrom subsides, Plant eases back and lets out one last sighing “and she’s buying a stairway to heaven” to close out the now-spent juggernaut.

Two important factors directly account for the outsized aura that shrouds “Stairway to Heaven”: its previously-detailed scope — master that song and you become the envy of all your friends — and the fact that—despite its instant appeal to the rock faithful and against the urgent pleas of Zeppelin’s record label, Atlantic—it was never released as a single. Oh, “Black Dog” was a single from

Led Zeppelin IV—but not “Stairway”. Page wouldn’t have it. His choice to keep “Stairway to Heaven” an album track ensured that record buyers would have to shell out for the entire LP, resulting in the record’s astronomical sales figures that place it near the top of any tally of the biggest-selling releases the industry has ever seen. And unlike many contemporaries, Led Zeppelin has been fiercely protective of how its music has been licensed, refraining from selling its songs to just any commercial or compilation with hefty wallets. If you pick up the generic “Rock Classics of the ’70s” best-of comps offered at your local department store, don’t be surprised if “Stairway” is a glaring omission from the tracklists. In most instances, if you want to experience the original recording by the group, you have to do it on the band’s terms: by putting on a copy of Led Zeppelin IV or, barring that, one of the official Zep compilations.

The effect of Zeppelin’s careful guarding of how its music is packaged and distributed is that even though radio has played the band to death, its songs have not become overfamiliar to the point of cultural mundanity as, say, certain tunes by Elvis Presley or the Rolling Stones or Aerosmith. The restraint Zeppelin has shown in selling “Stairway” has ensured that the song has to be uncovered by new listeners constantly as if it were some arcane talisman and not just another classic rock staple. There’s a chance that every few minutes or so, some teenager’s mind is being blown by hearing this song for the very first time. He or she may have an inkling of what they are in for, but nothing can fully prepare them for the eight-minute ride they are about to undergo.

So I guess the obvious question left to tackle is: is “Stairway to Heaven” the greatest rock song of all time? Well, maybe. I myself would rank Queen’s “Bohemian Rhapsody” (which admittedly drew inspiration from “Stairway”) a smidge above it. But it is an awesome undertaking, one that is fearlessly ambitious and succeeds at its lofty goals unquestionably. And having been one of those sense-shattered teenagers when I first encountered “Stairway”, I will never, ever forget the first time I heard it. If it’s not the greatest rock song ever, there are few legitimate contenders for that honor.

5.”Misty Mountain Hop”

The second half of Led Zeppelin IV is inaugurated with the sprightly “Misty Mountain Hop”, a fairly unassuming number to have follow up the heavenly grandeur of the album’s centerpiece, “Stairway to Heaven”. Compared to “Stairway” and every other cut on the LP, “Misty Mountain Hop” is an perfunctory exercise in pop formalism that doesn’t break the mould. It just gets in, does its business with little fuss, and then wraps up.

Like the 1950s-indebted “Rock and Roll” from the album’s first half, “Misty Mountain Hop” is essentially a stylistic throwback, this time one rooted in ’60s British Invasion pop/rock (though this song was recorded only a few short years divorced from that period, rock music was evolving by leaps and bounds in late ’60s and early ’70s). Based around a jaunty four note riff (originated by guitarist Jimmy Page, refined by bassist John Paul Jones), “Misty Mountain Hop” follows a very straightforward verse/chorus structure, with a middle section set aside for Page’s guitar solo.

Suiting its ’60s air, the lyrics are fixated on a rather topical concern for members of the Woodstock generation: flowers-in-their-hair-sporting hippies caught in a drug bust. The main bit of inventiveness on display in this song is how the verses alternate between multiple tracks of Robert Plant chanting in monotone — performed in a rhythmic manner that accentuates the quarter notes — and the singer’s solitary lung-bursting wails. Again, as on “Rock and Roll”, Plant’s performance, plus those of his bandmates (especially John Bonham’s scale-crushing drum beat), modernizes the form the band is playing with to the point where the homage becomes fairly fuzzy, only visible if you squint.

“Misty Mountain Hop” presents Led Zeppelin at the poppier end of its spectrum — and honestly, there’s nothing wrong with that at all, heavy rock aficionados. As other tracks on the album — and elsewhere in the Zep songbook — illustrate, it was healthy for the band to expand its range and tweak expectations. The track’s poppy nature is its virtue; it’s probable that it was the tune’s hookiness that earned it the honor of being selected as the b-side to the “Black Dog” single. No, what makes “Misty Mountain Hop” the least impressive offering from such a monumental album is that it plays far longer than it needs to. This song has the group tackling a form designed for optimal performance at around two and a half minutes, but here Zep extends it to nearly five. Such a basic riff and repetitious structure isn’t designed for that kind of overkill, which means the song gets pretty old before it’s even done.

Like every offering from Led Zeppelin IV, “Misty Mountain Hop” is an undying radio staple and has its share of fans, even if the track isn’t as ambitious or weighty as “Black Dog” or “Stairway to Heaven”. On the whole, it’s a decent, if basic, song — but imagine how improved it would be as a listening experience if a verse or two were taken out.

6.”Four Sticks”

Incessant radio play and millions of records sold worldwide over the last 40 years have made the various track selections from Led Zeppelin IV so ubiquitous and familiar, one can forget how unconventional these songs can be. Take “Four Sticks”, a hynpnotic raga-rock groover that alternates between 5/8 and 6/8 time (neither of which are common meters in popular music). In fact, the song proved so tricky to nail on tape that it was almost abandoned during the Led Zeppelin IV recording sessions, and was only played live once by the band, during a Copenhagen, Denmark concert in May 1971.

The title of “Four Sticks” clues listeners as to what finally allowed the song to be salvaged. Led Zeppelin’s secret weapon was not-so-secretly drummer John Bonham, the rough and tumble, heavy-hitting boozer whose incredible drumwork impressed even those who would normally find the British quartet’s music distasteful. The story goes that Bonham came into West London’s Island Studios one day after seeing former Cream stickman Ginger Baker’s new band Air Force, ready to give the tune–then under a working title—another go. Bonzo had been thoroughly impressed by his contemporary’s performance, but harboring a competitive streak, he was eager to one-up Baker right there and then. So a fuming Bonham downed a beer, picked up a pair of drumsticks in each hand, and laid down two phenomenal takes that wound up turning what henceforth became “Four Sticks” into a keeper.

It’s natural that Bonham would be the one to rescue “Four Sticks” from the dustbin, for as heard on record it’s the drummer who is the one who defines the track. Despite guitar and keyboard embellishments that stand out in the mix, the rhythmic nature of “Four Sticks” is its primary feature; there’s no guitar solo from Jimmy Page, and he and bassman John Paul John lock in with Bonham’s busy drumwork (who, per his job description, ensures everyone stays in time in the face of potentially-disorienting meter changes) instead of crowding the spotlight for themselves. Augmenting one another to form a three-man rhythm section, the entire band expands and contacts around the beat like the fluid inside of a lava lamp, but never abandons the main groove, for the groove is the song. Robert Plant’s amorous croons of “Ohhhh baby” ensure everyone is aware this is a Led Zeppelin song, but he too contributes to the Eastern vibe by singing an Indian-flavored melody as the tune draws to a closes.

Though “Four Sticks” never gained a regular spot in Zep’s setlists alongside “Stairway to Heaven”, “Whole Lotta Love”, and other heavyweights, like all the cuts from Led Zeppelin IV it has proven to be a reliable chestnut of rock radio, its trippy groove an unnoticed anomaly amongst more standard 4/4 time hard rock and heavy metal fare it’s often placed alongside. No one ever balks at “Four Sticks” and its atypical groove, for the song has become so ingrained as an accepted piece of the classic rock canon that it comes off as yet another stock example of loud rock convention, even though it is more than that. However, it’s always easier to stick to hard rock formula than to take a chance on a strange-yet-exciting detour, one that may only come together in the end because one of the performers wanted to upstage one of his rivals.

One final note: while Led Zeppelin only performed “Four Sticks” live on a single occasion, Robert Plant and Jimmy Page resurrected it (with orchestral backing) for their “Unledded” MTV Unplugged taping in 1994 and subsequent promotional ventures, and Plant still pulls it out for his solo excursions from time to time. Seems that beast wasn’t so hard to tame after all.

7. “Going to California”

The last of the two acoustic numbers on Led Zeppelin IV, “Going to California” is a full-blown ode to hippie idealism. Though cultural memory likes to draw a line under hippie movement following the disastrous Rolling Stones Altamont concert and the Manson Family killings in 1969 as well as the 1970 Kent State shootings, it was very much a major presence well into the ’70s. As I mentioned when discussing “The Battle of Evermore”, Zep frontman Robert Plant was—despite his rock ‘n’ roll “Golden God” image, which certainly wasn’t without its sizable grains of truth—an unrepentant flower child during the band’s early years, one who it seems could be just as content if he were to drop everything for a simple life living amongst unspoiled natural beauty. In “Going to California” he does just that: after spending “days with a woman unkind” who “smoked my stuff and drank all my wine”, he opts to hop on a jet plane headed to an idyllic California in hopes of finding “a queen without a king”.

The song originated at the same 1970 writing sessions at Bron-Yr-Aur in the Welsh countryside that yielded the bulk of the folk-leaning Led Zeppelin III. Its finger-plucked appreggios and wistful, longing tone were inspired by denizens of Los Angeles’ Laurel Canyon singer-songwriter scene, especially Canadian songstress Joni Mitchell, to whom the song is most likely a direct tribute to (take special note of the line “They say she plays guitar and cries and sings . . . la la la la”). It’s appropriately the gentlest cut from Led Zeppelin IV, an understated demonstration of the band’s ability to craft tranquil melodies as capably as it can bottom-heavy riff-rock.

Close your eyes while listening and you can practically inhale the fresh mountain air and smell the fields of flowers Plant hopes to reach. That is, if natural disasters (read: earthquakes, the perennial worry of Golden State residents such as myself) on the way don’t do him in first. In an echo-laden bridge section, Plant cries, “Seems that the wrath of the gods got a punch on the nose and it started to flow / I think I might be sinking”, his one trying moment of self-doubt in his odyssey. But soon it subsides as his quest for hippie Eden resumes, and as he continues to search for “a woman who’s never, never, never been born”, he reminds himself “it’s not as hard, hard, hard as it seems”.

During American dates leading up to the release of the group’s fourth LP, Zeppelin incorporated “Going to California” into a brand new acoustic section of its concert setlist, which premiered during that leg of the tour. Fans still smarting after the dearth of heavy metal bombast on Led Zeppelin III weren’t initially receptive to this portion of the show, which prompted Plant to shout “Shut up and listen!” from his stool to the skeptical crowd. Eventually they did open their ears, and like every other offering from Led Zeppelin IV, it’s a classic rock radio perennial, so much so that its sound has seeped into the DNA of subsequent generations of hard rockers who wouldn’t be expected to be too familiar with Joni Mitchell or Pentangle. Critics were quick to point out what the blatant spiritual godfather of grunge group Pearl Jam’s “Given to Fly” was when that song hit the airwaves in 1998, but they were by no means surprised. Zeppelin’s influence is so pervasive now even specific songs dictate how the language of rock music has developed—it’s matter-of-fatly accepted that of course a deep cut from the second half of a Zep album would leave its fingerprints on the work of top-tier rock groups more than two decades down the line.

As lovely as “Going to California” is, it ranks second to “The Battle of Evermore” as the album’s best acoustic offering. Compared to the urgent high drama that drives that song and its stakes-raising duet between Plant and Sandy Denny, “Going to California” is merely a pretty tune, a sedate respite from the rest of the record. But that’s true beauty of it in the context of Led Zeppelin IV–after all that bashing and riffing and hollering, it’s nice to have a moment to relax a little and savor the spirit of serene hopefulness conveyed by this low-key track. Even if you all you want is “Black Dog” times ten, at this point in the Led Zeppelin IV running order, “Going to California” is what you need to hear. You know, Jimmy Page might have been onto something with this “light and shade” contrast he strove for on his band’s records after all.

8. “When the Levee Breaks”

It really is rare that a classic album ends with one of its finest tracks. Most albums are front-loaded (in the days when the vinyl LP were the primary product format, this meant both sides would kick off with a bang, meaning many full-lengths from days past boast a mid-point second wind on CD pressings), so with all the top material already exhausted, the dregs are often shoved into the closing minutes in the hopes that spent listeners will be too worn out to notice. This is definitely not the case when it comes to Led Zeppelin IV. The British rock legends’ impeccable fourth album ends with the seven-minute “When the Levee Breaks”, a standout that’s amassed acclaim to rival any other offering from the record bar the unconquerable “Stairway to Heaven”.

Led Zeppelin’s “When the Levee Breaks” is a heavy (both figurative and literal) reworking of the 1929 song by Memphis Minnie song and Joe McCoy, about the massive flood that devastated the state of Mississippi in 1927. Only Minnie receives a credit on Led Zeppelin IV–which is a definite improvement today, since original the album didn’t credit anyone outside of the band at all. Like with Willie Dixon’s songwriting credit on “Whole Lotta Love” from Led Zeppelin II (1969), recognition of Minnie McCoy came after the fact, and is just another example of the group’s problematic relationship in regards to properly acknowledge the source material it derived (primarily, but not exclusively) words from on its earlier compositions.

Not that Led Zeppelin’s rendition has much in common with the original. The lyrics are the most recognizable component, hence the joint credit with Memphis Minnie but not her husband. On the album, Zeppelin stretched out and reimagined what was originally a jaunty acoustic blues number as a hypnotic portent of doom, intended to bewitch and mesmerize awestruck listeners. Page contributed to the vibe by purposely slowing the tune down and playing a 12-string guitar in an open G tuning to give it the appropriate cavernous element he was aiming for. But from the second the track begins, it’s obvious that it’s the earth-shaking drums of John Bonham that elevate the song to greatness. Already a notoriously hard-hitting stickman, the sound of Bonham’s beat was achieved by placing his kit at the head of the staircase in the entrance hall of the Headley Grange manor where the album was recorded. The acoustics in the hall were so favorable that Bonzo’s kick drum didn’t need to be directly micced—microphones were merely hung from the second floor. Bonham’s weighty groove is justifiably seminal: no matter how foreboding Page’s slide guitar is or how much singer Robert Plant wails, it’s Bonham who really has the final word on Led Zeppelin IV.

It’s appropriate that one of the greatest heavy metal records of all time (even if every track isn’t a power chord-laden skull crusher) ends with such an immense track. Heavy metal was essentially birthed by white Britons playing overamplified blues, and on “When the Levee Breaks”, Zeppelin provides a clear demonstration of the links between the source material and the future of rock ‘n roll, links which are overlooked by the “Black Sabbath invented the genre out of whole cloth” myth that’s become more and more pervasive in the last decade. The birth of metal wasn’t a sudden epiphany; it was a logical evolution of developments in rock music stretching from the 1960s into the 1970s. And Led Zeppelin was right there at that transition point, standing on the crossroads, tying various musical strains together into a greater whole. While “When the Levee Breaks” is the bluesiest cut from Led Zeppelin IV, it is blues as played in the postindustrial rock ‘n roll age, where superstar bands are intercontinental conquering heroes who wield amplified guitars instead of swords or guns.

Though Led Zeppelin IV has had an undoubtedly large influence on rock music in the past 40 years, it has a sizable legacy in hip-hop and electronic music as well, due to numerous artists sampling the beat to “When the Levee Breaks”, including the Beastie Boys, Dr. Dre, and Massive Attack. There’s no great mystery as to why this is so: one listen and it’s plainly evident to both headbangers and B-boys that this is one ginormous-sounding drum track.