“For every parameter that you can control, you must control.” This is the first law that Wendy Carlos has always adhered to as a composer and electronic music pioneer. Her groundbreaking work is the result of a high level of intelligence matched with hard work and perseverance, but it’s always been tempered with a complex personal life that has colored the way journalists and fans have perceived her. Born in Rhode Island in 1939 and assigned the name Walter Carlos and the gender male, she transitioned to female in the late 1960s and eventually underwent gender confirmation surgery in 1972 – after she gained worldwide notoriety with her revolutionary debut album, Switched-on Bach, in 1968.

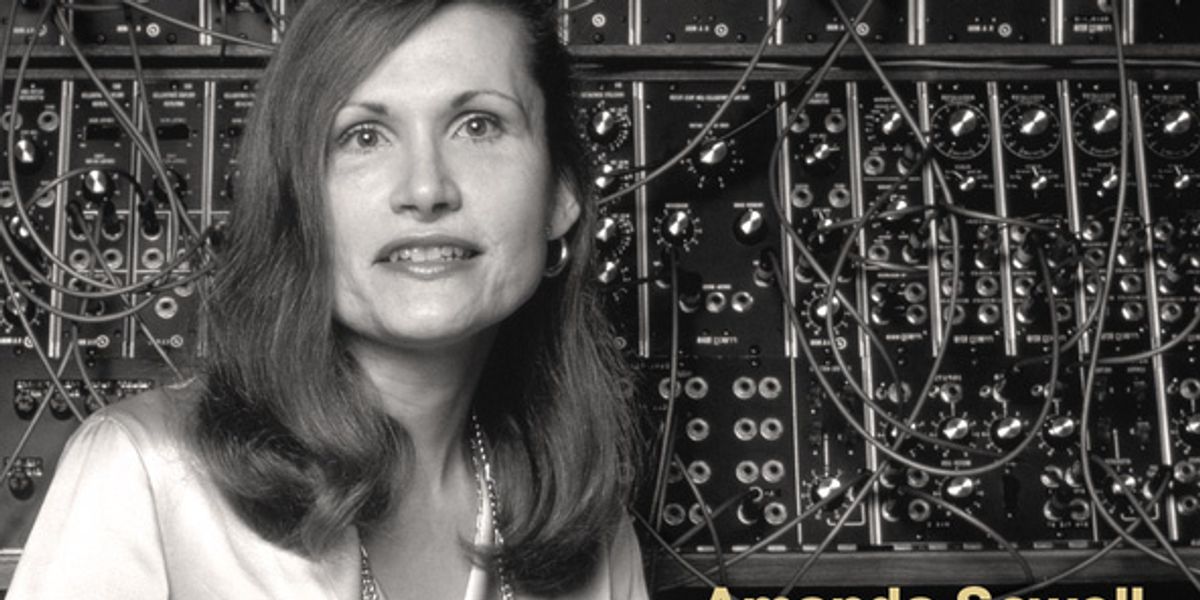

Amanda Sewell’s biography of Carlos is noteworthy in that it manages to be primarily about Carlos the composer, the musician, the vanguard of electronic music. While her gender identity is certainly written about in great length, it’s never approached as a morbid curiosity. If anything, it’s used primarily to chronicle the challenges Carlos encountered around society’s preconceptions and prejudices toward transgendered people.

Carlos, who has maintained an understandably combative and aloof relationship with journalists, did not respond to repeated requests to be interviewed for this book. Many people who have worked with Carlos over the past six decades have also declined or refused to participate. In the hands of a lesser writer, this can result in a biography that comes off as exploitative and gossipy.

This is not the case here. Sewell used the many published interviews that Carlos has given since the late 1960s and relied heavily on an extensive interview published in Playboy magazine in 1979 that was essentially the public’s introduction to Wendy Carlos after several years of mistakenly knowing her as “Walter Carlos”.

Sewell writes about Carlos’s early years growing up in Rhode Island, working through her antisocial childhood by developing a keen interest in the nascent field of electronic music. “The anxious, bullied teenager, working alone for hours in her parents’ Rhode Island basement laboratory,” she writes, “was independently developing many machines that would become the leading commercial audio trends during the 1960s.” After earning a combined music and physics undergraduate degree at Brown University, she later pursued a master’s degree in electronic music at Columbia University in New York, where she has lived ever since.

Carlos’s years at Columbia led to a personal and professional relationship with synthesizer pioneer Robert Moog, whose state-of-the-art instruments and equipment helped Carlos create the electronic classical music opus Switched-on Bach. This debut album was a commercial and critical smash, even prompting classical pianist (and often harsh critic) Glenn Gould to call it “one of the most startling achievements of the recording industry in this generation.” But while the success was clearly advantageous to Carlos, it also underscored her personal struggles as she was transitioning to female and unable to effectively promote her music without giving away her transition, an enormous personal step she was not ready to make.

Sewell writes exhaustively and in great detail of the work Carlos continued to produce – alongside her professional companion and collaborator, Rachel Elkind — during the rest of the ’60s and through the ’70s, including 1969’s The Well-Tempered Synthesizer, her contributions to the soundtracks of Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange and The Shining, and albums Sonic Seasonings (1972) and By Request (1975). She also enjoyed the unique hobby of eclipse photography, which is well-documented here.

During this intensely fertile creative period, Carlos was frustrated with her inability to perform or appear openly with fans and scholars. It wasn’t until she was interviewed by journalist Arthur Bell for the aforementioned wide-ranging Playboy magazine interview that the world would know her as Wendy Carlos. While the interview was partially designed to clear the air about her gender identity, Carlos had hoped that it would primarily be concerned with her music, and at that point she was finished talking about her transition. “She had no interest in being a spokesperson or an advocate for the transgender community,” Sewell writes. “She was a ‘normal’ woman, and that was the end of it.”

Throughout the ’80s and up until the late ’90s, Carlos continued to compose and release music with varying levels of critical and commercial success. The advent of the internet brought an opportunity to present her music and opinions to an enormous audience through her personal website. Sewell writes of Carlos’s often unvarnished opinions on everything from synthesizer technology to digital recording capabilities to less-than-kind music journalists.

A staunch defender of digital technology over analog, Carlos released her music on compact disc through the label East Side Digital, but eventually the label folded, and all licenses were reverted to their owners. Not only are all the East Side Digital titles out of print, Carlos – who is enormously critical of the MP3 audio format – has prohibited her music to appear on Spotify, Pandora, YouTube, or any other streaming services.

Carlos’s insistence on essentially making her music nearly impossible to hear in the 21st century poses an obviously frustrating problem for readers of this fascinating biography. The music is so well-documented and lovingly described, that readers who have not previously purchased her music in the now-deleted physical formats are not able to call up the albums on streaming devices can be maddening. That virtually no new interviews have been conducted in the writing of the book is actually less of a problem. Sewell’s research is impeccable, and although the lack of fresh quotes can occasionally result in a few dry stretches, this is often essentially an entertaining, often revelatory work, truly befitting a legend and a trailblazer.

* * *

Editor’s Note: Due to the ramifications of the COVID-19 virus, publication date of this book has been changed from May 2020 to September 2020. We are reminding readers about this fine book again by reposting this article in September 2020.