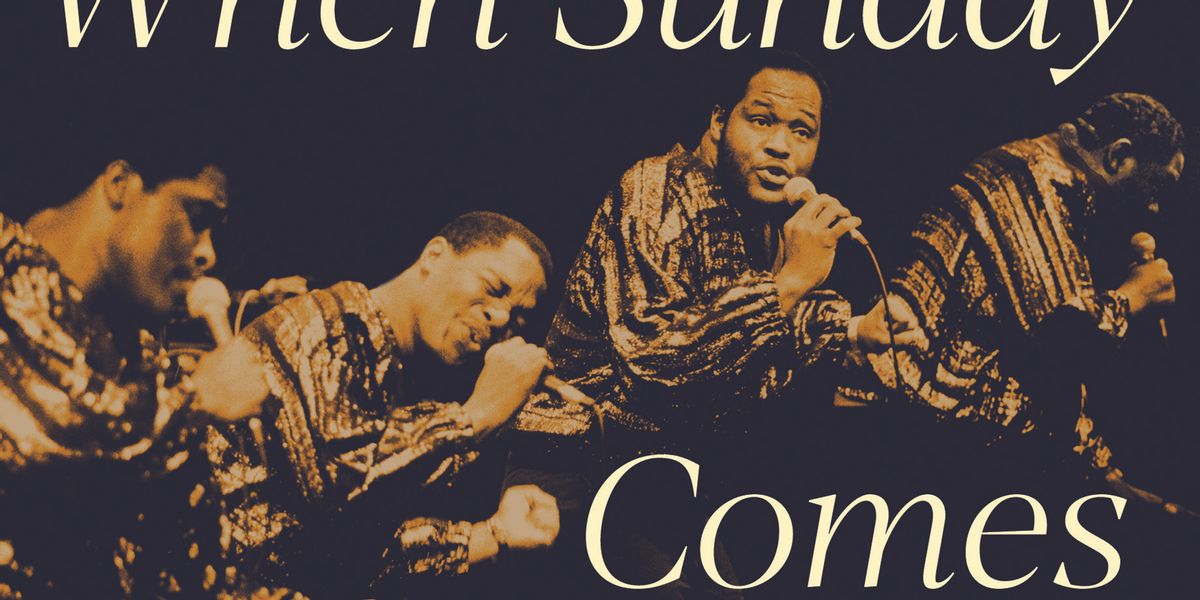

Excerpted from When Sunday Comes: Gospel Music in the Soul and Hip-Hop Eras by Claudrena N. Harold (footnotes omitted). Copyright 2020 by the Board of Trustees of the University of Illinois. Used with permission of the University of Illinois Press. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Chapter 1

Lord, Let Me Be an Instrument

The Artistry and Cultural Politics of Reverend James Cleveland

The bluesman, who comes out of the black Christian culture, is telling the story differently. He has good news, but his news puts a different kind of hurtin’ on the gospel. His news says this: If I sing my blues, I’ll lose my blues—at least for those precious moments when I’m singing. His news says that the story of our lives—our losses, our depression, our angst—can be simplified and funkafied in a form that gives visceral pleasure and subversive joy, both to the bluesman and his audience.

—Cornel West, Brother West: Living and Loving Out Loud, a Memoir

Angel Wings by Zorro4 (Pixabay License / Pixabay)

On Thursday night, January 13, 1972, an eclectic crowd of music lovers assembled at New Temple Missionary Baptist Church in Los Angeles to witness Aretha Louise Franklin deliver one of the most amazing performances of her career. The atmosphere in New Temple was electric as Franklin’s soaring shouts and deep moans sent chills down the spines of women and men, blacks and whites, regular churchgoers and self-proclaimed atheists. On such gospel classics as “What a Friend We Have in Jesus,” “How I Got Over,” and “Precious Lord, Take My Hand,” she fused the optimistic spirit of the civil rights movement, the cultural ethos of the Black Power era, and the prophetic vision of the black church to create a transcendent work of art.

The following night, Franklin returned to New Temple to deliver another round of gospel classics. Once again, she mesmerized the audience with her vocal prowess and radiant spirit. Her set included a sublime version of “Amazing Grace,” a magnificent reworking of the Caravans'”Mary Don’t You Weep,” and a scorching duet with gospel legend James Cleveland.

Four months later, Atlantic records released Franklin’s magical performances as a double album titled Amazing Grace. Across the country, journalists heralded s Franklin’s latest offering as a sonic masterpiece. “She sings like never before on record,” raved journalist Jon Landau in Rolling Stone. “The liberation and abandon she has always implied in her greatest moments are now fully and consistently achieved.”

Rarely acknowledged in public conversations about Franklin’s triumphant return to gospel was her competitive spirit, specifically her desire to demonstrate a mastery of the art form—gospel music—that had been so central to her identity as an artist. Since signing with Atlantic Records in 1966, Franklin had released some of the most celebrated albums in pop music, most notably I Never Loved a Man the Way I Love You, Lady Soul, Spirit in the Dark, and Young, Gifted, and Black. Despite her phenomenal success in the secular world, Franklin wanted to return, if only momentarily, to the sacred music of her youth.”I told Atlantic that it was time for me to return to my roots and make a gospel album,” she stated in her autobiography. Such an album, she insisted, must be recorded live with a real congregation. It also had to include her mentor and close friend Reverend James Cleveland. “No one could put together a choir like James Cleveland,” Franklin recalled in her memoir. Indeed, Cleveland’s collaborative endeavors with Detroit’s Voices of Tabernacle, the Angelic Choir of Nutley, New Jersey, and his own Southern California Community Choir had resulted in some of the most commercially successful recordings in gospel music history.

Unwavering in his commitment to expanding gospel’s influence and popularity, Cleveland appreciated the opportunity to participate in what he knew would be a historic event. With approval from his record label, Savoy, he agreed to contribute to Franklin’s gospel outing by directing the choir, playing the piano, emceeing the live recording, and lending his voice on the duet “Precious Memories.”

Franklin’s insistence on Cleveland’s involvement in Amazing Grace was a testament not just to her faith in his artistry but also to his unrivaled stature in the gospel music industry. With his signature voice, distinctive phrasing, and innovative choir arrangements, Cleveland had scored a series of hits during the 1960s. In addition to releasing groundbreaking records like Peace Be Still and I Stood on the Banks of the Jordan, he performed sold-out concerts throughout the United States and Europe. An ambitious musician whose artistic goals extended beyond his own individual success, Cleveland wanted to secure greater respect and recognition for gospel music’s integral role in the spiritual nourishment and cultural advancement of black America. Toward this end, he established the Gospel Music Workshop of America in 1967. Under his dedicated leadership, the GMWA provided an institutional space in which black artists could hone their craft, gain exposure to the latest developments and trends in gospel music, exercise greater control over the marketing of their art, and fellowship with like- minded musicians who shared their religious convictions. The GMWA’s annual conventions brought together artists, concert promoters, ministers, disc jockeys, n radio programmers, A&R directors, and fans. Its success led Cleveland and his associates to pursue an even bigger project in the mid-1970s: the formation of a gospel music college in Soul City, North Carolina. The proposed college would further institutionalize Cleveland’s artistic vision and evangelical mission and enhance the GMWA’s outreach work among black youth.

An imaginative leader with an indefatigable work ethic, Cleveland was part of a growing community of black artists, writers, and religious figures who were reevaluating and redefining the meaning of black sacred music and its place in the black freedom struggle. In many ways, his advocacy work on behalf of the GMWA complemented the intellectual pursuits of scholars like Horace Boyer, James Cone, and Pearl Williams-Jones who promoted gospel music as an integral component of African Americans’ ongoing quest for self-definition. Williams-Jones, in particular, led the way in challenging writers to consider seriously the religious music of African Americans in their discussions on the black aesthetic: “If a basic theoretical concept of a black aesthetic can be drawn from the history of the black experience in America, the crystallization of this concept is embodied in Afro-American gospel music.” No longer, she maintained, could black arts writers concern themselves solely with secular forms of black cultural expression.”In order to establish a black aesthetic definition as applied to black art forms, the implications of the black gospel church and the music associated with it should be brought into focus.” Echoes of Williams-Jones’s arguments appear in the works of several black cultural artists, from Cannonball Adderley (“Country Preacher” and “Walk Tall”) to Donald Byrd (“Pentecostal Feeling” and”Cristo Redentor”) to poet Nikki Giovanni, who celebrated the black church as a “great archive of black music.” Giovanni’s engagement with that archive was most explicit on her 1971 recording Truth Is on the Way. On this critically ac- claimed record, Giovanni covered James Cleveland’s classic”Peace Be Still.” Her selection reflected her view of the sacred songs as an abundant cultural resource for African Americans, as well as her vision of Cleveland as the embodiment of the genre’s best traditions and possibilities: “I dig gospel,” Giovanni proudly proclaimed, “especially James Cleveland, he’s saying a whole lot.”

To Giovanni and many other African Americans, the music of James Cleveland had special resonance. Songs like “Peace Be Still,” “I Stood on the Banks of the Jordan,” “Lord Help Me to Hold Out,” “God Is,” “Please Be Patient with Me,” and”Lord Do It for Me” captured not just his artistic brilliance but also the complexity and beauty of the African American odyssey in the United States. To be sure, the gospel superstar enjoyed a level of material comfort that escaped most of his followers, but in the opinion of many of his working-class supporters, he spoke their language, articulated their pains, and gave voice to the hope that sustained them in the darkest times.

One night in 1968, a staff writer for Ebony magazine had the opportunity to bear witness to Cleveland’s deep connection with his fans. Sitting in Harlem’s famed Apollo Theater, watching Cleveland sing as audience members danced down the aisles, the writer struggled to process, let alone convey, the emotional power of Cleveland’s artistry. That night, Cleveland wowed his audience with several hits, but one song in particular drew a visceral reaction from the crowd: “‘Lord Do It’ is what the song is called and the words have special meaning there in Harlem where most folks reckon that just about the only one who can ease the black-poor pain is the one that they learned about back home down South—the Lord. James Cleveland sings as if he agrees, and he squeezes the mike and tightens up his face, and his whole body shakes as he shouts the words that get to the people.”

Cleveland’s impact on African Americans not just in Harlem but throughout the United States was profound. The same can be said for his influence on the evolution of black sacred music in the post–civil rights era. For more than twenty years, he was the dominant figure in black gospel music as both an artist and an institution builder. His accomplishments commanded the respect of fellow artists within and beyond the religious world.”I want to do for black publishing what James Cleveland does for gospels,” writer Toni Morrison declared in 1974.

* * *

Claudrena N. Harold is a professor of African American and African studies and history at the University of Virginia. She is the author of New Negro Politics in the Jim Crow South and The Rise and Fall of the Garvey Movement in the Urban South, 1918–1942.