If one wants to write a book about a rock ‘n’ roll band, there are only two ways to do it: give new information that adds to the band’s legacy or chop up old information in a new way that reframes the ongoing conversation about the band. If the band is no longer operating as a unit because its lead singer is dead, as is the case with Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers, reframing is the right road, though it remains a rocky one.

As all Pettyheads know, there are only two true primary sources of new information about their heroes:

Paul Zollo’s direct and highly detailed series of interviews with Petty himself in Conversations (an expanded edition was released by Omnibus in 2020), and Warren Zanes’ authorized psychological portrait Petty: The Biography (Henry Holt, 2015). All other books about the band are secondary sources heavily reliant on Zollo and Zanes, usually augmented with a narrow selection of local newspaper articles chosen for their ability to aid in reframing commonly known information from those primary sources.

One frequent debate about Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers is which region has the stronger claim to their legacy: Gainesville, Florida, repping for the South, or Los Angeles repping for California? Enter

Christopher McKittrick. McKittrick’s previous book, also for Post Hill Press, Can’t Give It Away on Seventh Avenue reframes the Rolling Stones in light of their affiliation with New York City. The case for the Heartbreakers as Angelinos is self-evidently stronger than that, as their Gainesville story concluded when they got in the van to head west in search of a recording contract. Their subsequent Los Angeles success story lasted 40 years. Yet it was a long time before LA’s music industry and the local press could lay claim to the Heartbreakers—a fact that Petty himself was often angry about and seldom let his adopted home forget.

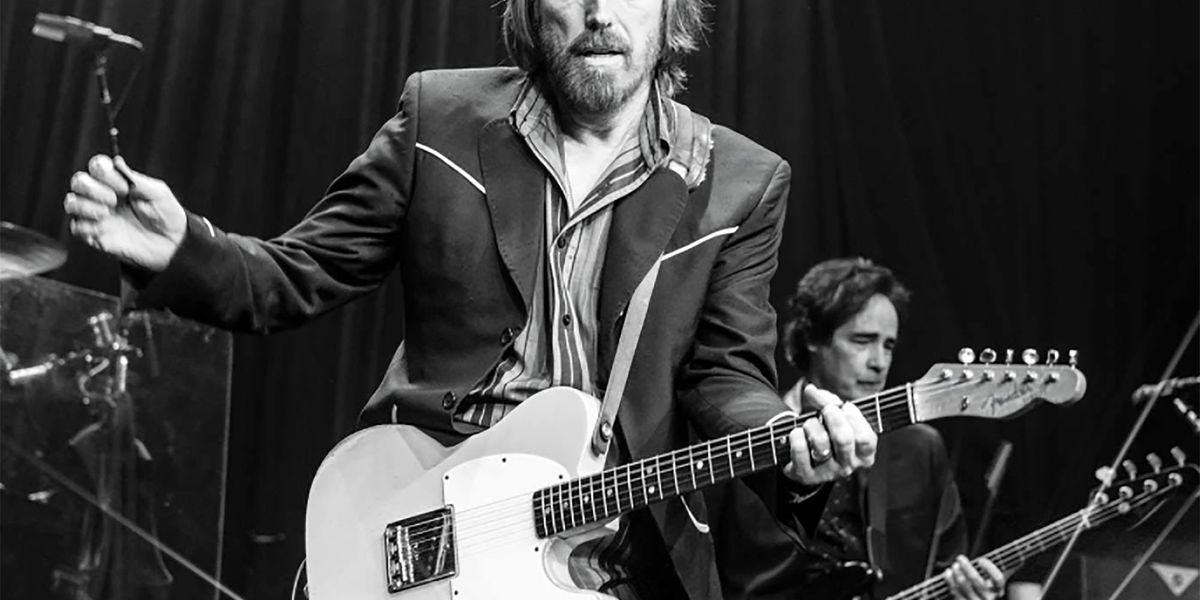

Guitar-Fender-Pink by rahu (Pixabay License / Pixabay)

Before I cracked open McKittrick’s book, this question loomed large in my mind: how can you reframe the conversation about Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers to be more about California when telling the band’s story is necessarily already 90% taking place in California? The litmus test was basically whether one could read Somewhere You Feel Free and arrive at a greater understanding of the Heartbreakers’ relationship to the Los Angeles music scene without knowing that California is supposed to be the focus of the book.

If one can read Zanes and argue that his biographical project is just as much about California as McKittrick’s is purporting to be directly emphasizing California, then McKittrick’s project would be a failure. Based on this test, my judgment is that Somewhere You Feel Free is only about 30% successful. That’s not necessarily bad. It means firstly that casual fans can enjoy this book without significant prior knowledge of the band because it essentially functions best as a general biography. It means secondly that there’s decent use of local Angelino newspaper articles and some solid effort to focus on Californian elements, so that the book may somewhat bolster that side of the West versus South conversation.

Will diehard Pettyheads devour McKittrick’s book? Will the enormous Petty Nation online fan community rave about it as the next big thing? Nah. It’s a mildly interesting addition to the completist’s bookshelf, but not something to turn toward over and over again as the years go by. There are two reasons for that, and the first is structural.

Somewhere You Feel Free is ordered chronologically. Why? McKittrick’s emphasis should be on all the ways Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers is connected to Los Angeles, and this could be much better done by operating thematically. Common focal points in any conversation about the Los Angeles music scene are historic concert or recording venues and their preservation, the epicenter of the business side of the industry and connections to Hollywood filmmaking, the role of session musicians and organic collaboration happening between musicians living in the same neighborhoods, and the importance of charitable works to give back to the community. McKittrick’s book contains a good amount of information on all these topics, but because he’s intent on telling the story of the band from beginning to end, none of these topics is adequately foregrounded as a special feature of the relationship between the band and the land.

The second challenge, stemming in part from the initial poor choice to operate chronologically, is that McKittrick offers plenty of facts that focus on California with very little analysis as to their final importance or any concrete argumentation concerning the above themes. For example, regarding each tour, he only talks about the California dates with a template that includes the venue name, the number of tickets sold, any notable items in the setlist, and a smattering of quotations from local reviews of the show.

Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers, 1977. ABC/Shelter Records. (Wikipedia / public domain)

Diehard fans will appreciate the repeated reliance on reviews written by Ben Wener for the Orange County Register, who is himself a very astute superfan. Sometimes McKittrick will point out that this was the only time Petty ever played a certain song or played at a certain venue, but he stops short of making any meaning out of these informational nuggets. He sticks to the objective facts so closely that he tends to miss the forest for the trees. For another example, his sole line on the Winterland ’78 show lists it as “an infamous concert in San Francisco, where Petty was pulled offstage by enthusiastic fans during a performance of ‘Shout'” (46), when in fact Petty said he walked off the short riser into the crowd and would never do it again because they so ravaged him that he said he was spooked by the incident for the rest of his life.

That’s a missed opportunity to reflect on the nature of California’s music scene, and there are many such missed opportunities. The epilogue concludes that “the Heartbreakers appear to be the end of that line” (238) of Laurel Canyon groups from the Sixties like the Byrds and Buffalo Springfield, but there’s no mention of Petty’s impressed curiosity about the unique fandom of the Grateful Dead, even though I can’t imagine a more Californian conversation than that.

There are quotations of song lyrics specifically related to the city, but no substantive analysis of them. The author uses about two dozen quotations from Robert Hilburn’s coverage of the band without ever delving into Hilburn’s role as definer and arbiter of the Angelo music scene through his position as chief music critic for the Los Angeles Times, particularly when some exploration of Hilburn’s obsessive Dylanology might’ve helped McKittrick build further linkages between Petty and Dylan to bolster his chapters on the Heartbreakers’ extensive touring with Dylan in 1986 or the formation of the Traveling Wilburys in 1988. The closest he gets is by saying, “The strong reviews and Hilburn’s frequent mentions of the band in his column were having a significant impact on their growing popularity in Los Angeles” (35).

Telling you all this is giving me the blues. I liked McKittrick’s book as I like basically all books on Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers, but I wanted to love this book. It just doesn’t offer up enough freshness of perspective with which to fall in love. The author got partway into a really viable focus on California-related facts, but his strict adherence to those facts was done at the expense of the bulk of usefully contextual analysis, and the chronological approach to the band’s history locked out any meaningful conversation about California.

There’s one more thing that, in the Californian spirit of how a dollar is a vote, that I really ought to mention: McKittrick’s heart may be in the right place with this project, but I’m quite sure Tom Petty would not be a supporter of the press that published it. Post Hill Press is an independent publisher in Tennessee whose 600 or so products lean heavily toward the religiously Christian and the politically conservative. Petty was inarguably neither of those things, and he likely wouldn’t be keen on a press that lists among its bestselling books Congressman Matt Gaetz’s Firebrand: Dispatches from the Front Lines of the MAGA Revolution, Dan Bongino’s Follow the Money: The Shocking Deep State Connections of the Anti-Trump Cabal, and Adam Corolla’s I’m Your Emotional Support Animal: Navigating Our All Woke, No Joke Culture. Maybe a chunk of Petty’s Gainesville-oriented fanbase is cool with all that, but likely not so much the Angeleno contingent.