In 2008, Chinese journalist Yang Jisheng published Tombstone, a now-definitive account of how Mao’s ill-considered plan to industrialize the nation failed to bring about the intended Great Leap Forward and instead caused the Great Famine. Jisheng—a former reporter for state news agency Xinhua, whose father was one of those who died of starvation—used his access to dig into previously un-reported documents about the catastrophe. He discovered that between 1958 and 1961 at least 36 million Chinese died as a direct result of Mao’s delusional mismanagement.

Though Jisheng was hailed around the world for this thoroughly documented accounting, Beijing was less thrilled. Jisheng was not jailed for his work, but Tombstone was banned in China and could only be found via the now-defunct Samizdat editions. He was not allowed to leave the country to accept the prizes sent his way after foreign editions published in 2012.

Jisheng’s limbo state of overseas acclaim and domestic silencing is likely to become even more acute with this year’s release (outside of China, at least) of The World Turned Upside Down: A History of the Chinese Cultural Revolution. Since his death in 1976, Mao Zedong has been viewed by the regimes that followed with a complex mix of veneration and limited critique. While Mao is no longer viewed as nearly divine in his infallibility, Beijing nevertheless sees any direct critique of the Community Party’s founder as an attack on its own authority. As a result, the many black stains on his record, such as the Cultural Revolution, are viewed with oblique criticism that nevertheless relieves Mao of most of the blame.

In this great slab of a book, Jisheng dissects how Mao—whom he portrays as a curiously detached architect of human misery on a vast scale—set in motion a nation-disrupting campaign of continuous revolution for no better reason than to ensure his fate did not match that of Nikita Khrushchev, topped from Soviet leadership by a “bloodless coup” in 1964. Two years later, Mao issued what came to be known as the “Sixteen Articles”, which laid out a template for uprooting what he claimed were hidden reactionaries and counter-revolutionary bourgeois elements in the 17-year-old Communist state.

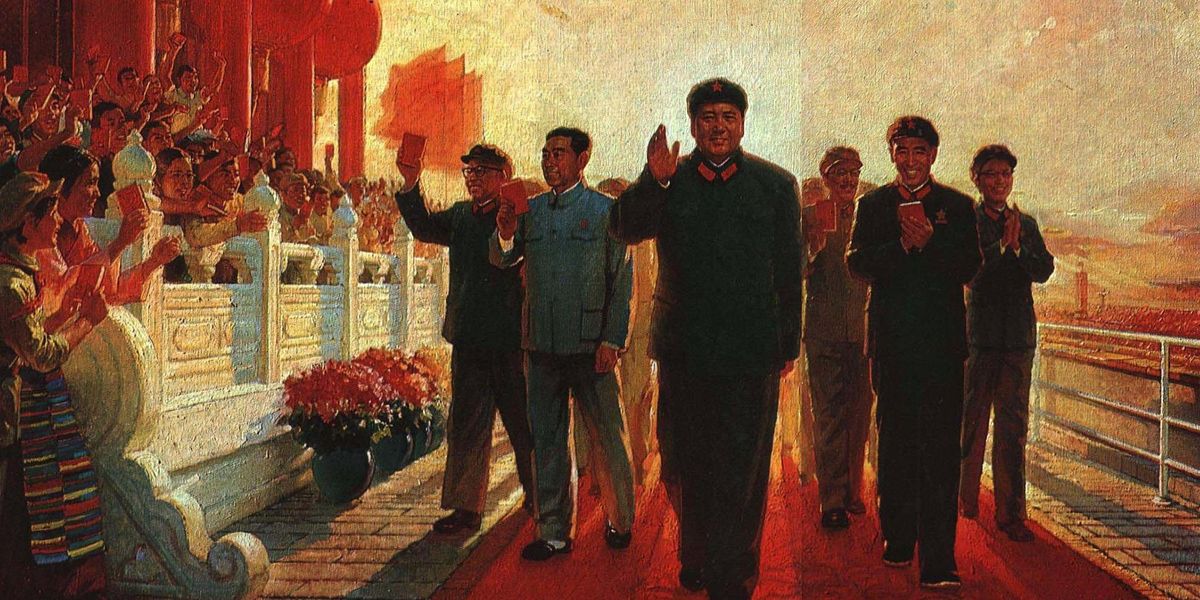

Somewhat typical for Mao, however, while he directly encouraged the Red Guards (a radicalized nascent student movement that theoretically targeted repressive Soviet-style schooling but also threatened any teachers or students they saw as insufficiently working class) to heighten their attacks on the status quo, he was also vague in how such things should be carried out. Jisheng calls many of the Sixteen Articles concepts undefined, “making them impossible to implement in practice and creating confusion and chaos.” The potential for such confusion leading to widescale violence was only heightened between August and November of 1966 when Mao led a series of mass rallies in Beijing of unprecedented size (some 12 million people total) to whip up the Red Guards and launch them into the nation to carry out his Cultural Revolution.

The first Red Guard fatality recorded by Jisheng took place in August 1966, days before the first mass rally. Bian Zhongyun, a vice-principal at a Beijing secondary school, was beaten to death by students. Other vice-principals and teachers “were tortured for more than three hours with nail-spiked boards and scalding water.” The often family-based violence—using what they called “blood lineage theory”, Red Guards targeted people who came from so-called “black category” families—spread through Beijing schools, marked by brutal beatings and public humiliations. One secondary student poisoned herself to death after the Red Guards announced a rally to “help her”. The virus of fanaticism, fueled by years of propaganda hammering home the infallibility of Mao, quickly spiraled out from Beijing throughout the country.

For the first few years of the Cultural Revolution, China ripped itself apart in a frenzy of finger-pointing, denunciations, and pogroms. The combination of didacticism, divinely-ordained illogic, and thirst for public declarations of guilt (preferably following sessions of torture) reads like the Spanish Inquisition as carried out by the Khmer Rouge. The litany of horrors is medieval at times, ranging from public executions to salting of wounds, burning with irons, live burial, death by disemboweling and spear, and even isolated instances of cannibalism. After writing a letter criticizing Defense Minister Lin Biao (who was later fatally purged by Mao after a supposed assassination plot), Shi Renxiang had his throat cut before being executed “so that he couldn’t say any last words.” During the 66-day-long massacre of 1967 in Doaxian, there were so many bodies in the Xiaoshui river that they clogged the dam and could be smelled for miles around.

Scrupulous in his detailing of the Cultural Revolution’s horrors and insanities, Jisheng often fails to explain just how such a thing came about. The numbers and dry descriptions of atrocities stun but also numb. He explains the god-like status that Mao was held in, and goes into quite lengthy detail about the behind-the-scenes Beijing machinations that started as power plays between varying Mao rivals and sycophants before rippling out into China proper.

But too much of the book is spent on palace intrigue and not nearly enough on the devastation and trauma that this decade-long eruption of mass violence and erasure of culture inflicted on the people who survived. By quoting one of the perpetrators of the Daoxian massacre answering an official questioner years later—”The higher-ups told me to kill, so I killed. If they told me to kill you now, I’d do it”—and describing how bureaucrats felt safer over- than under-reacting to rumors of reactionaries, Jisheng shows the extent of the fanaticism. But he never illuminates just how Mao and his clique turned so much of the country so savage so quickly.

Jisheng writes that while reporting on the Cultural Revolution for Xinhua, he “missed the forest for the trees”. Although The World Turned Upside Down is a staggering piece of documentation, it still often misses the intimate scope which would have helped bring this epic tale to life. There are times when Jisheng’s writing resembles that of a court document. He includes somewhat endless lists of names of the Party functionaries involved in this or that meeting to celebrate or denounce the latest state media-approved newspaper piece or “big character” propaganda poster (the regime’s primary method of communicating their intents) that Mao had expressed this or that opinion on.

The World Turned Upside Down is a necessary book, and it’s an admirable attempt to get the record down. But that does not keep it from resembling a massive research archive with crucial information, rather than a work of human-scale history.