It is tempting to think America, and the world, lost something precious on 17 July 2020, with the passing of Rep. John Lewis and Rev. C.T. Vivian on the same day. Both of them were stalwarts of the Civil Rights Movement in the ’60s as young men, and continued their activism the rest of their thankfully long and full lives. Lewis’ public profile was larger than Vivian’s, thanks to being a longtime member of Congress and the telling of his story on numerous platforms. (Including the graphic bio trilogy March, which I read in the weeks after Donald Trump was elected president, and which turned out to be a good preparation for life under his presidency). Yet Vivian was well known in post-Movement circles, and both men were widely respected elders to later generations of activists.

We might think their deaths severed our tangible links to past struggles and victories, leaving us without direct witnesses and testimonies to the conviction and bravery it took to earn those victories. But that’s not quite true. Lewis and Vivian were indeed titanic figures, but they weren’t alone.

In 1961, they were among hundreds of Americans — Black and white, men and women, college students and working professionals, trained activists and energized newcomers, people of various faiths, from every part of the country — who successfully challenged Southern segregation of train stations and bus depots in direct defiance of a U.S. Supreme Court ruling. They would become known as the Freedom Riders.

The first bus of Freedom Riders was attacked and blown up outside Anniston, Alabama; the Riders barely escaped with their lives. (Lewis was supposed to be on that bus but had obligations elsewhere). Another bus was ambushed by Ku Klux Klansmen. Buses of Freedom Riders were greeted by official resistance, by bodies from state and local governments to the news media, at every stop on their way to Mississippi, their ultimate destination. But they kept coming. Wanting to be at least a little circumspect about their intentions, states charged the riders with the seemingly minor offense “breach of the peace”.

By the end of that summer, the Riders had achieved their goal. National outrage led the White House to finally get involved, and work towards ending what had become a nasty standoff in Mississippi, where many Riders were sent off to notorious Mississippi State Penitentiary in Parchman, and ensure desegregated traveling accommodations.

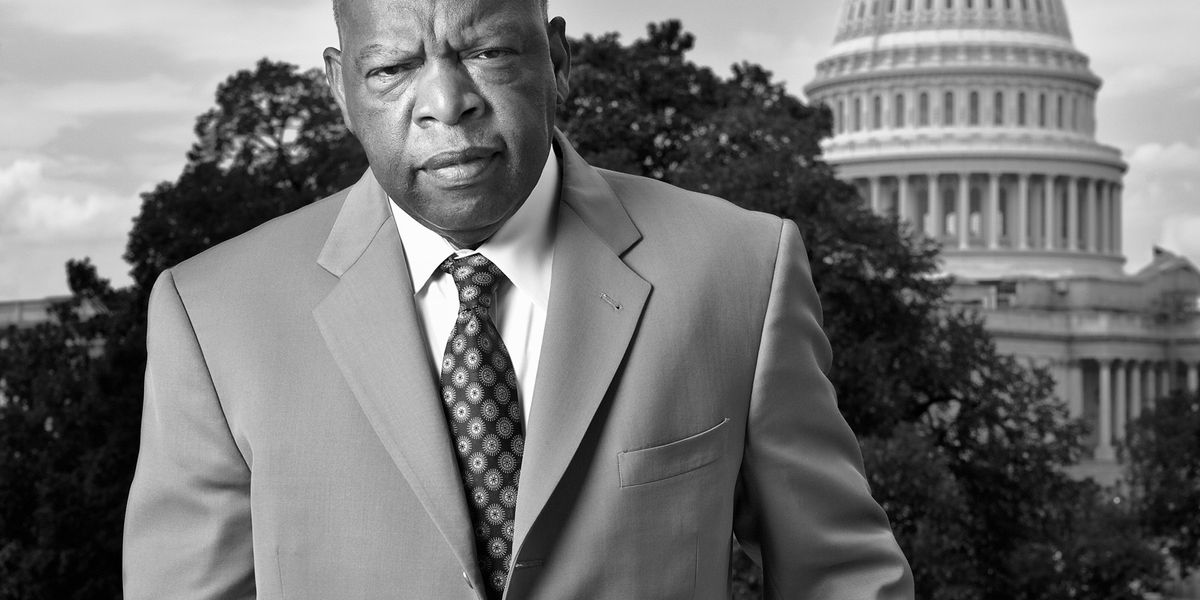

John Lewis [Photo © Eric Etheridge, courtesy of Eric Etheridge. All Rights Reserved. No image may be reproduced or reprinted without permission of the photographer.]

But in addition to harassing the riders and slow-footing compliance with federal law, the state of Mississippi took an additional measure. The Mississippi State Sovereignty Commission, established in 1959 to monitor and document racial activism, kept meticulous records of all the arrests they made, including front and profile mug shots of the Riders. In the late ’90s, years after the commission ended its business and after some court wrangling, those records were made available to researchers, and in 2002 to the general public.

Journalist Eric Etheridge, who was a young boy just outside of Jackson at the time of the rides, was taken by the clarity of the images, and embarked on a remarkable then-and-now project. He contacted former Riders, captured their recollections of those days, and took striking present-day photos (in black and white, to match the mug shots). They were collected in the first edition of Breach of Peace: Portraits of the 1961 Mississippi Freedom Riders (Atlas & Co., 2008). An updated version with additional interviews was published in 2018, and stands as a lasting statement about how, for many of the Riders, a moment in time charged a lifetime of fighting for justice.

Most of the Riders aren’t household names, unless your household was part of the movement back then or connected to its succeeding iterations (but there is a pre-Black Power Stokely Carmichael, who served time at Parchman along with Lewis). But many continued to make a progressive mark in their post-Rides lives. Here are just a few examples:

- Peter Ackerberg became an attorney who helped implement a federal consent decree on behalf of Black farmers.

- Jerome Smith teaches New Orleans children about their local culture and history.

- Pauline Knight-Ofusu was the first female pesticide inspector at the Evnviromental Protection Administration.

- Carol Silver works to promote access to education for girls in Afghanistan.

- Marv Davidov led a successful campaign to get Honeywell out of the weapons-making business.

- Bernard Lafayette, Jr. helped craft a curriculum for teaching nonviolence, which schools, community groups and even police departments across the world have used.

- Lula White was arrested in 2002 at a sit-in supporting Yale University union workers.

But all of them, it seems, value their experience as Freedom Riders. Some wrote memoirs of those days, and many have spoken widely about it, especially after a celebratory 50th anniversary reunion in 2011. To show how life can sometimes work, a memorial to the rides was established in Anniston, Alabama in 2017.

Dave Dennis [Photo © Eric Etheridge, courtesy of Eric Etheridge. All Rights Reserved. No image may be reproduced or reprinted without permission of the photographer.]

What sings through Etheridge’s brief profiles is the sense of conviction they brought to getting on those perilous buses, and how that sense never left them. Several riders expounded on their experience in longer interviews, including Vivian, whose activist work began with desegregating a lunch counter in Peoria, Illinois in 1947. His interview was conducted for the first edition, yet reads like it could have happened just weeks before he passed, 13 years later:

“Any dictator doesn’t want anybody to say anything about his dictatorship, because obviously, he’s going to create violence, but then also obviously, he’s going to blame it on the victim. We didn’t play that game.”

“What these liberal white fellows in the South were saying is that the non-liberals down here are gonna kill you, and you know we’re not gonna say anything to them, and we won’t be able to help you. This is ther unspoken stuff now. And without our help, why, you could never make it, because you must have us talking to white people. And we were saying, that’s your importance, all right, but you haven’t freed nobody.

“This is the genius of Martin [Luther King], who spoke the whole thing so well, week after week, month after month, from that time on. Until we are in charge of our own freedom, there is not gonna be freedom for any of us. As long as we allow someone else to speak for us, and they know each other very well, there’s not gonna be a breaking of the old order. We’re still going to be killed whenever any policeman decides to. And they are always gonna be covered up if they care to cover it up at all.

“Who’s going to be honest enough to cut through this? This is who we are. We know we can be killed in the process. So? We’re gonna get killed anyway. But we’re not gonna do it without it being obvious, and we’re not going to do it withut it being all over the world, and we’re not going to do it playing the game of your so-called democracy, which is undemocratic.”

Breach of Peace isn’t a full-fledged history of the Freedom Riders, but it could well serve as balm and inspiration for today’s activists confronting death and destruction on any number of levels, be it from disease, social and economic inequity, a planet without the proper environmental stewardship, or whatever other plague. Keep on keeping on, keep on fighting the good fight, this book says to them. Victories are possible, and so is a better chance of thriving beyond them.

Yes, we lost something precious with the passing of John Lewis and C.T. Vivian, but we can take comfort knowing that, because they passed on the same day, their souls had a traveling companion on their ultimate ride to freedom.

* * *

Work Cited

Reynolds, Mark. ” Culture in the Age of Trump”. PopMatters. 5 January 2017.

Margaret Leonard [Photo © Eric Etheridge, courtesy of Eric Etheridge. All Rights Reserved. No image may be reproduced or reprinted without permission of the photographer.]