Familiar as I am with the paradoxes of life in modern industrial housing, that the more humans are packed into concrete compartments the more atomised they become, such spaces are conceived through ideas about modern utopias and socialist dreams. Irrespective of whether it’s the banlieues of Paris, or the Stalinist mega-estates of the former Soviet bloc, cast in each and every cubic millimetre of these precast spaces is a strain of utopia. Nowhere was that as bold or as advanced as in the vast estates of the former East German republic.

In the old GDR, over a third of the population lived in large estates symbolised by the so-called plattenbau. Plattenbau literally translates as platte-bau or slab-house. The prefabricated slab-house building program began at Marzahn in the 1970s. The prototype of the generic place of home for everyone. Here was the doctor and the lawyer next door to the factory cleaner and the waiter. . Thus ‘the slab’ die platte was not only a form of architectural construction, but in the GDR epitomised the new place of home. A plattetopia, the topia of the home that symbolised the marriage of society and state.

It’s 2016 and I have come to stay in Lichtenberg in East Berlin, a bit further out from the fashionable districts of Kreuzberg and Friedrichshain. After the unification of 1990 die Wende, or the ‘peaceful revolution’ as the Germans know it, Lichtenberg, unlike Friedrichshain, remained neglected. Over two decades it acquired a notoriety as much for its Far Right skinheads as its anarchist squats. But just as the Far Right moved eastwards, gone are the days of streets of squatted communes. Now Lichtenberg is on the front-line of gentrification and property speculation as real estate moves in.

I am staying in a neighbourhood on the edge where the spread of socialist plattebau housing begins. Still undesirable for the gentrification game. I move into an apartment on the 10th floor of an ex-GDR housing block at Ruschestraße Lichtenberg to be met by views I did not expect. They look straight into the old Stasi headquarters, which now serve as temporary housing for Syrian refugees. It’s like having a ringside seat wherein I can peer into their privacy.

Former Stasi HQ Ruschestraße. April 2016. Photo ©Siraj Izhar.

Former Stasi HQ Ruschestraße. April 2016. Photo ©Siraj Izhar.

Spying on refugees in their temporary accommodation in a former secret service HQ is an insight into the contortions and distortions of history. To see their sequestered lives from above is also an understanding of the commonality irrespective of circumstance: that to live in these complexes is to live at the mercy of the “system” – to surrender to forces outside one’s control, to mass bureaucracy and to an impersonal scale of administration and planning. My window at Ruschestraße in one single sight-line beholds the dream and the nightmare of the socialist state.

East from here, on the other side of the train tracks, are the vast enclaves of slab-housing at Marzahn and Hellersdorf; and just north from Ruschestraße is Hohenschönhausen, with its Stasi interrogation centres and prison complexes at Alt Hohenschönhausen, surrounded by a sea of slab housing. These spread north to Neu Hohenschönhausen and then onto the housing satellites of Wartenburg and Ahrensfelde. For anyone interested in the GDR legacy of East Berlin, these slab housing sprawls remain as their testimony, fables of its socialist vision. In my exploration of that legacy, here I return in 2019.

Photo by Aarón Blanco Tejedor on Unsplash

Settling into my residency at an altbau (old house) studio above the Lichtenberg Museum, I follow the footfall along the signature Berlin overground sewer pipes and under the rail arch to a housing estate by Coppistraße. There is a dis-used bit of green space, which I enter to find another notion of home – the self-made home of a homeless person. A shed, about three meters by one meter, held together by cast-off wood and rusty nails. Partly hidden from view by trees and shrubs, it symbolises a home free from all bureaucracy: the independent life of the “homeless”. I find a laid-out table, duvets, cutlery, books, cds, electronic gadgets, but no one at home.

This “home for the homeless”, in its irony of naming and its dishevelled display, has, at remove, a purity in its pure use value as shelter. It has nothing to do with home as an embodiment of state regulation or private property. The dissociation of home from property is to be found in the utopia of Thomas More. More’s narration of utopia as a fictional island of fulfilling and fully human life is made possible only by the absence of any conception of property, private property. The abolition of property is equally at the foundation of the modern socialist utopia. However the conflict between the idea and reality of any utopia can be found right here.

They may be in stark contrast to one another, yet the self-made shed and the slab housing overlooking it both stand against the notion of home as private property that arose out of an “original sin” of primitive accumulation. In Capital Volume 1 (1867) Marx spelt out this correlation of sin and accumulation, which in modern times turned the commonwealth in property and the home into a commodity. In his words, “.. primitive accumulation plays in political economy about the same part as original sin in theology. Adam bit the apple, and thereupon sin fell on the human race.” Comparably, both of the homes here, are symbols of escape from this sin.

Lichtenberg Coppistrasse. January 2020. Photo ©Siraj Izhar.

Lichtenberg Coppistrasse. January 2020. Photo ©Siraj Izhar.

I visit the empty shed, as a reminder of modernity’s original sin now sitting outside the regulated, every day on my morning walks. But it remains empty, even over the Christmas week. I grow bolder in my use of the spaces around this isolated shed, appropriating the deserted spaces with its throwaway debris as a workspace for my ideas about the home in modern society. These ideas have become split between the notions of home I see here, which draw from the conflicted place of home in my own life and work.

The socialist utopia assures the right to a home, a home de-commodified, but its regime of state regulation compromises the right to space, right to the city. Against it, is the other, the escape, the renunciation–here in the efforts of those who still forage for their home outside the law. The (unoccupied) shed is a different claim to space by the unregulated life that lives outside the state regime with its freedom for self-making. Between these homes lies a primal dilemma of life and its regulation that haunts the making of utopia.

Translated into the complexities of our modern society and the socialist state, this dilemma consumes the work of the urban sociologist Henri Lefebvre, particularly in his theories on the failure to connect the life of the everyday to modern social space. In his book The Production of Space (1974) Lefebvre asks, “has state socialism produced a space of its own? The question is not unimportant. A revolution that does not produce a new space has not realized its full potential; indeed it has failed in that it has not changed life itself, but has merely changed ideological superstructures, institutions or political apparatuses.”

For Lefebvre, the modern revolution of space, of abstract space as the new space of power, already bears the seeds of its assured demise. The new space dissolves old space but from its beginning the transparency of modern space is duplicitous as it represses the lived experience. Nowhere can this be understood more forcefully than in the modern housing of Lefebvre’s Paris and its concrete banlieues, the stage-set of cult nihilistic films like Mathieu Kassovitz’s la Haine (1995).

On modern social space, Lefebvre writes of it as an “impersonal pseudo-subject”, yet “concealed by its illusory transparency–the real ‘subject’, namely state (political) power.” Further, Lefebvre continues, “Within this space, and on the subject of this space, everything is openly declared: everything is said or written. Save for the fact that there is very little to be said–and even less to be ‘lived’, for lived experience is crushed, vanquished by what is ‘conceived of’.”

The socialist State as the sole arbiter of space and the lived life could not hide its repression. The GDR welded the State and space together. Seen from the outside, it was where, as in the lyrics of Bowie’s “We Can Be Heroes” (1977), all the shame fell – on its side of the Wall. With the fall of the Berlin Wall came the licence to take a wrecking ball to its nightmare of repression so it would never come back. But there began the unwritten violence of Die Wende, the peaceful revolution that hides the Oedipal violence of one order killing another.

With the formal unification of Germany in 1990, a new chapter of capital emerges as capitalism extrapolates its space by usurping the state all together. The entrapment of space in its regime of commodity dominates life without exclusion. The greater the reach of its own repression, the more use of the reminders of the socialist version, the totalitarianism, the secret police, the reduction of life to drab utility, and so on. These have become capitalism’s alibis to enclose us entirely in its web.

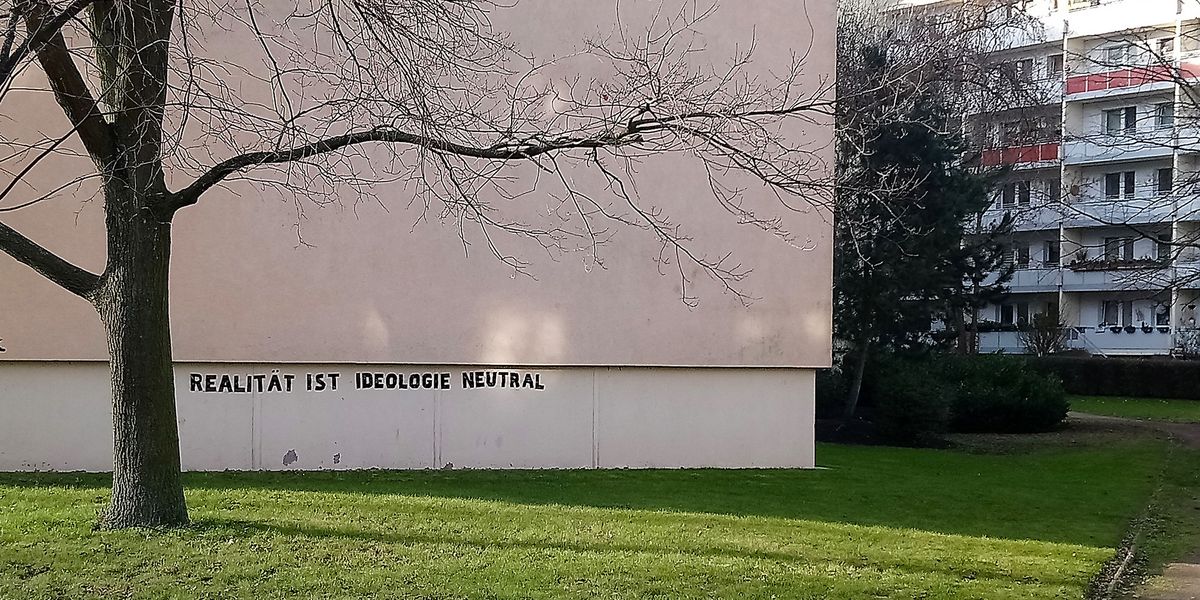

Can it ever be possible again to read an innocence or neutrality in the small chapter of history called the Die Wende? With that question, I return to Hohenschönhausen to make a direct insitu intervention on the vast banks of blank prefab walls that the plattenbau offers. But I am quickly reminded that I am an invader. A resident who appears out of one apartment interrupts me in a clearly unapproving tone. He doesn’t understand that my work, which reads ‘Realität ist Ideologie neutral’ against the backdrop of neutral grey slab concrete (above) has only the one purpose: to be a photographic record of itself. In half an hour the work is gone from sight, along with me. My work as an art intervention was only an exercise for other questions to emerge.

These questions on modern space and socialist space come as much on commuter journeys on the S-bahn trains and trams in-between these vast housing estates. Staring out of moving windows at the horizon of industrial housing; meaningless journeys in that experience of time called boredom. I wonder if J.G. Ballard, author of novels such as High-Rise (1975) and Concrete Island (1974) ever came to East Berlin. Ballard left an unrelenting narrative examination of the modern concrete environment, yet there is little in his writing on socialist space other than the odd interview, as in The London Magazine (2003) on the Soviet era. “The end of social utopia? Yes…” he says, to follow with his reading of its totalitarian dystopia.

The politics of Ballardian space lies entirely in capitalism; in his writing, capitalism is the sole author of modern space and also as the psychopathology that will destroy it. Concrete and material consumption fuse into a destructive spiral. The “vertical zoo” of Hi-Rise is “environment built, not for man, but for man’s absence”. Ballard gives up on any possible redemption of modern space. His future vision, as he put it in his 1962 essay, “Which Way to Inner Space?” lay in the “inner space-suit” that explores our inner horizon in a new genre of sci-fi.

This emphasis on inner psychological space was also famously elaborated in a 1968 interview for the German TV channel Munich Round Up:

“I define inner space as an imaginary realm in which on the one hand the outer world of reality, and on the other the inner world of the mind, meet and merge.”

I think of this while riding on the Berlin S75 train to Wartenberg or the S7 to Ahrensfelde. From station to station I see nothing but prefab plattenbau housing. Between the blur and the reflections of the landscape outside, the compartment of the moving carriage is my experience of this space in the compartments of the inner world. Grappling with notions of how to connect them, I turn to the psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan who, through his progressive evolution of the mental tools needed, provides a way.

Specifically, Lacan’s famous formulation of the imaginary, the symbolic, and the real as the psychic processes, by which our minds grow and coil around the world outside and vice versa. This entwining is three-fold; from the imaginary as we seek to find our own mirror-image in the alien space outside us, to the symbolic by which we create a sense of unity, to the real, that which lies beyond us, outside our capacity of representation. Each as a word may feel almost self-explanatory, though we learn further from the reader of Lacan, the philosopher Slavoj Zizek. The imaginary, the symbolic and the real to examine how our sense of self and the space we are in and its objects converge. And whether this fulfils or fragments us.

Hohenschönhausen Zingster Strasse. January 2020. Photo ©Siraj Izhar.

Hohenschönhausen Zingster Strasse. January 2020. Photo ©Siraj Izhar.

Walking into the concrete estates at Hohenschönhausen, the rhythm of the body changes. This is so even in the softened landscape of the managed social spaces of these concrete industrial estates. We become conditioned but to know such spaces is to know the mental change that comes when its sanctuary of the domestic shuts out the form of commonality that modern space offers us–of corridors, lifts and stairwells, and beyond the spaces with no sense of belonging. Regimented lawns, hedgerows maintained by the invisible hand of bureaucratic management. If this describes the quintessential modern space that drains the sense of self, Lefebvre in The Production of Space writes that, “each living body is space and has its space: it produces itself in space and it also produces that space”.

Hohenschönhausen, Ahrenshooper Strasse East Berlin. January 2020. Photo ©Siraj Izhar.

Hohenschönhausen, Ahrenshooper Strasse East Berlin. January 2020. Photo ©Siraj Izhar.

And this is what I experience at Hohenschönhausen–not a passive social space but an experience of making space, producing space, a process of reclamation of space from its ennui. The real in the form of modern space may have cut the hidden strings of the imaginary that connects us to a sense of place; or it may have displaced the symbols that ground us, but Hohenschönhausen is a tableux of reclamation: of regrowing, replanting what the modern removes. At one level this is done by the officially sanctioned giant murals that transport our minds out of here, to some seascape or some bucolic imagining. But more pervasively all around by escapist scatterings–on refuse bins, post boxes and so on.

The old church steeple, the picture-book fairy tale cottage, the castle tower reappear. Ballard writes that concrete has its own consciousness, yet here is a struggle against it by an appeal to heimat, the German concept of home through the tradition that modernity foreclosed.

The reclamation of space doesn’t stop; there are layers on layers almost unseen. Space that belongs to the world of anonymous taggers whose imaginary rejects the order of managed regularity. The tags are signatures, symbols of resistance, hidden transcripts comprehensible only to their authors. Marks of self-recognition that allow them to claim their place in this space.

Hohenschönhausen Zingster Strasse. January 2020. Photo ©Siraj Izhar.

Hohenschönhausen Zingster Strasse. January 2020. Photo ©Siraj Izhar.

Why is all this significant to our understanding of the spaces we inhabit today? Because it tells us the role we play wherever we are in the reclamation of place, at least on the imaginary and symbolic level. Space, as the real, is not only given, it is always also made. Not by means that is always recognised, but ways by which we bring life to the civilizational dead-end that capitalist space confines us to; to prevent its inevitable descent into the psychosis that is Ballardian modern space. We don’t redeem modern space but yet we save it. We ward off, to use a Freudian analogy, the “sensory castration” modern space has forced upon us using the canny and uncanny.

In his classic essay ”

The ‘Uncanny'” (1919), Freud contrasts the canny or heimlich – the “familiar”, “native”, “belonging to the home” with the unheimlich, the uncanny, unhomely, and ultimately what “belongs to all that is terrible”. We need these games to claim our space. The Hans Christian Anderson cottage or the mad King Ludwig castle, like the gnome in a suburban garden, are our antidotes as much as the unwanted defiling scrawls of taggers. They are aesthetic scarecrows we produce to mirror our inner world.

Out of modern ennui, I can see symbiotic games at play. They are war games of the imaginary and symbolic against the real. A game between the seen and the unseen, games by which what

is unheimlich comes to be heimlich and vice versa. It is how Freud suggests in his essay, “what is supposed to be kept secret but is inadvertently revealed”. But once discovered, it can be followed. Picture to picture, tag to tag. The more I look, the more I find. Which I do and what I find I mark discretely and tag onto my Google Maps. This way I will locate it again to reclaim it as my own finding. An exercise of seeking and finding, to reclaim the unseen from oblivion. A exercise that leads me into the corners of Hohenschönhausen, alt- and neu-, and onto Arendsfelde, and Wartenburg. And where I go, I leave my mark.

Hohenschönhausen, Ahrenshooper Strasse East Berlin. January 2020. Photo ©Siraj Izhar.

Hohenschönhausen, Ahrenshooper Strasse East Berlin. January 2020. Photo ©Siraj Izhar.

It’s a bright sunny midday in Hohenschönhausen. I am lingering at a corner of Ribnitzer Strasse by an electrical box marked by a street tagger TRN, quietly tagging the tag for my own purposes. An elderly man stops to talk. He introduces himself as Uwe (pronouncing it as ‘ee-we’ not the German ‘oo-vay’). “That’s the English way,” he says for my consideration as he explains he had worked briefly in Scotland, in the north Sea industry. Uwe has lived on the estate for almost 40 years since it was built in 1984 (as we can see from the old newsreels of Hohenschönhausen). With his girlfriend in West Berlin, his is a story of love across the Wall. He recounts the time when she was given a permit to see him, and vice versa; of how they compared his small apartment dis-favourably to her altbau West Berlin flat. Yet after the Wall fell she moved in with him at Hohenschönhausen, only to die tragically before her years.

Within Uwe’s life story I find narrations of inversions I was seeking to resonate with the greater tragedy of inversions in a history of socialist space. Of unfulfilled hope. Aborted reality. If the tragedy of it all could be laid solely at the door of the socialist state, behind the re-clad blocks are the residues of its ambition that people here have moved on from.

But though the Wall die Mauer officially ceased to exist in 1991, it remains a charged symbol. Germans speak of the Mauer im Kopf–the Wall in the head, the wall that remains, the wall that still separates the eastern (ossie) from the western (wessie.) Of course, it referred more to the head in the East, the complaining Jammer ossie. If the metaphor of the Wall wanes with time and a new generation, it still plays a role here in what has to be repressed. The abortion of the 20th century socialist project–the narrative of socialism as the utopia of modernity, cannot be erased so easily.

Hohenschönhausen, Ahrenshooper Strasse East Berlin. January 2020. Photo ©Siraj Izhar.

Hohenschönhausen, Ahrenshooper Strasse East Berlin. January 2020. Photo ©Siraj Izhar.

In the re-cladding of the plattenbau, what I see are attempts to hide a broken thread of narrative. To draw on Freud’s essay, the “unheimliches house” of the plattenbau is now to be estranged from its own history by the process of repression. But these vast tracts of concrete are resistant to the storyline of the organic unification. Hohenschönhausen resists that. The Wall of die platte is the wall that still stands to separate itself from the Berlin that swallows other GDR neighbourhoods like Prenzlauer Berg and now claims Lichtenberg, street by street.

It may be that home here is no longer the home of society at large, the home of the doctor next door to the waiter and so on. Instead, the unification, die Wende, has made this the space of the left-behinds, overwhelmingly working class Germans alongside those who have no choice in where they are asked to live. The refugees and migrants. Hohenschönhausen, of course, is no ghetto, it epitomises the managed order of the managed revolution whose narrative of the peaceful revolution remains inadequate. Here is a world apart from the Berlin across the train lines to the west. By its separation, an air of impasse hangs on this place, as if it is in a transitory hold between the past that must be banished and a future to come. The present is a compromise of history, an autopsy of die Wende, the unification.

Wartenberg. January 2020. Photo ©Siraj Izhar.

Wartenberg. January 2020. Photo ©Siraj Izhar.

In this compromise of history, between the past and future, I follow Lefebvre’s injunction to create my own space. My understanding of it has changed in the course of my walks and rides and my countless interventions that no-one will notice. But by them I can connect my experiences and encounters here into the place of my own. Plattetopia. Not as nostalgia for the socialism that produced the platte-bau as the home for all, but as a deeper search into the genesis of modern space and the question of home and property in it.

My walks are an investigative exploration of its utopia, the slow death of the socialist utopia and abduction of modern space by capital and property. It has fallen to me to gather evidence from the everyday whose strength lies in its rejection of the given narratives of history.

On my last day in Lichtenberg on the 31st January 2020, I go back to the self-made shed at Coppistraße where I started, but the state bureaucracy has caught up with it. Perhaps as a portent, I find it removed without a trace. Perfectly in a way that it never existed at all.