“Where does Kate Bush come from? You can’t hear her influences”, said English rapper and actor Tricky for the 2014 BBC documentary The Kate Bush Story. “I can’t figure out, musically, artistically, who her mother and father is [sic].”

Bush is a musician whose forebears are hard to find; direct lines cannot be drawn or easily discerned, though faint echoes call back to David Bowie, Roy Harper, and Pink Floyd. Never for Ever—Bush’s third album, released in September 1980—obscures those bloodlines even deeper. The result is a transitional album for her, one that moves away from art-pop ingenue toward a maturing artist in command of her powers. Never for Ever is a rare feat of parthenogenesis, with Bush reproducing and reinventing herself along the way.

To understand Never for Ever as a catalyst for the rest of Bush’s career, some context is needed. As though flung from outer space, the 19-year-old became an overnight sensation in 1978, with the release of her debut LP: The Kick Inside. Seeking to strike while the iron was hot, her record label pushed for a follow-up before the close of the same year. She had barely performed live at that point, but she’d already amassed over a hundred songs, some composed when she was only 13. Seven (out of ten) of those songs appear on her second LP, Lionheart, which was released in time for Christmas.

By 1980, she had mounted the successful “Tour of Life” (which, it would turn out, would be the only tour of her life), along with its concomitant live EP and concert film. But, she was eager to write new material and learn the studio side of things; she had assisted Andrew Powell in producing Lionheart and wanted to have the technical reins all to herself.

Never for Ever was a commercial success, yielding three UK Top 20 hits (“Breathing”, “Army Dreamers”, and “Babooshka”) and topping the UK Albums chart. She produced the album, along with engineer Jon Kelly. For some artists, this achievement would be enough, and they’d be content to churn out variations on a theme year after year. But not so for Kate. On Never for Ever, we see her evolve lyrically, hear her expand sonically, and get a taste of what’s to come. Bush’s influences may be hard to map, but Never for Ever plots a course to the frenzied experimentation of The Dreaming, the triumph of Hounds of Love,, and indeed to the rest of her career. Hence, Never for Ever serves as a bridge between where she started and where she was going all along.

The album opens with “Babooshka”, which reached number five on the UK Singles Chart. A classic story song—with a conflict, rising action, and eventual climax—it’s loosely based on the English folk song “Sovay”, which presents a tale of disguise, deception, and paranoia. A sinewy fretless bass stands in for the man in the story, weaving its way around the narrative as he approaches his incognito wife. When her trust has been broken, and his betrayal laid bare, the sound of breaking glass pierces the song at its climax, then trails off at its denouement.

Design Face Eye by Geralt (Pixabay License / Pixabay)

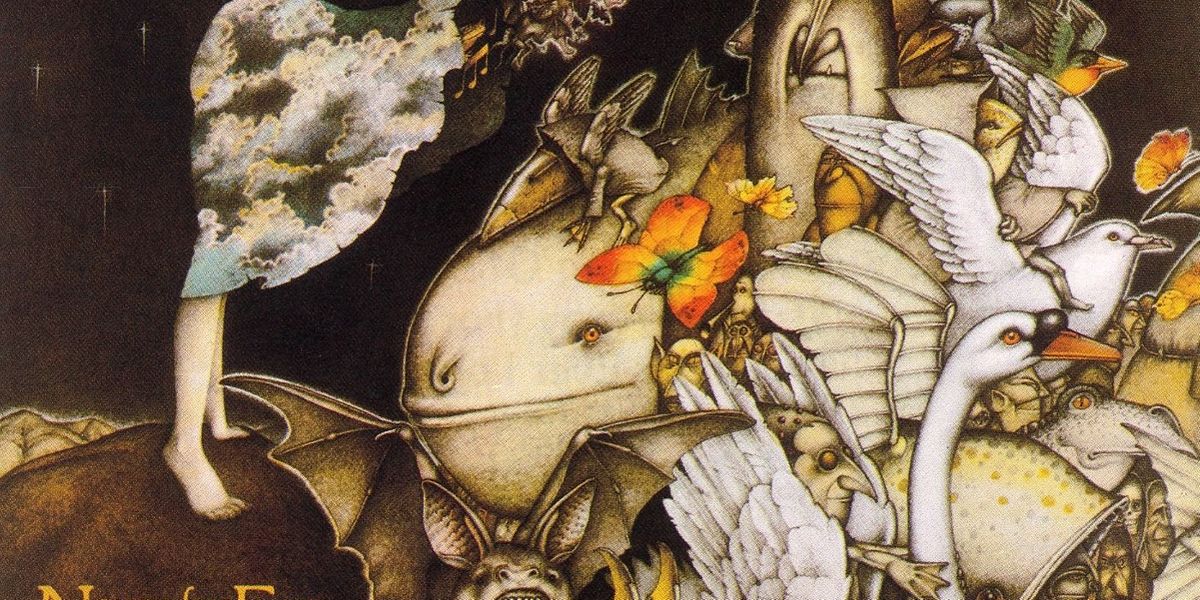

Bush created the glass-breaking sound with the Fairlight CMI (as well as a few items from the Abbey Road kitchen), the revolutionary digital sampler introduced only a year earlier. She first saw the new instrument thanks to Peter Gabriel, when she sang backing vocals for his third eponymous album (known as Melt). The Fairlight’s impact on Bush’s creative process was profound: she was no longer tied to the piano and the decorative orchestral arrangements of her first two LPs. Rather, she could now write songs based on an infinite array of sonic textures. With the addition of other synthesizers — like the Yamaha CS-80 and the Prophet, as well as the Roland drum machine — she could create entire symphonies in a four-minute song. Bush had always used a menagerie of musical instruments, but the Fairlight freed her imagination. And, just like the mythical creatures flowing from beneath her skirt in the album’s cover illustration, once it was let loose, there was no going back.

It is on these songs, in particular, that listeners catch a glimpse of what’s to come. Tracks like “Delius”, with its dreamy and capacious soundscapes, are intermixed with tracks like “The Wedding List”, a sort of companion piece to “Babooshka”. With its dastardly narrative building to a dramatic chorus, “The Wedding List” is a showy vaudevillian number. But it relies on the conventional instruments and string arrangements of Bush’s earlier LPs and would have been at home on either one.

“Blow Away” and “All We Ever Look For” are sweet, sentimental songs that could also fit in the pre-Fairlight era. I particularly enjoy Kate’s voice on the latter, but the Fairlight samples of a door opening, Hare Krishna chanting, and footsteps seem to have been an afterthought. The samples add a narrative layer to the song, but the sounds are not integral to the arrangement.

“The Infant Kiss” is one of the highlights of the album, though it, too, is more of a throwback to earlier compositions. The eerie song was inspired by the film The Innocents, which was in turn based on the Henry James novella The Turn of the Screw. Lyrically, the song is similar to the title track of The Kick Inside and “The Man With the Child in His Eyes” in its dealing with taboo sexuality. The song’s narrator is a governess torn between the love of an adult man and child who inhabit the same body. Or, as one critic called it, “the child with the man in his eyes.”

What sets this song apart is Bush’s production. Instead of overwrought orchestral arrangements of the earlier albums, Bush relies on restrained, baroque instrumentation to convey the song’s conflicted emotions. With Bush behind the boards, she begins to use the studio as an instrument unto itself. Her growing technical facility, combined with the expansive possibilities of the Fairlight and other synthesizers, allowed her to express her feelings through sound more fully.

The penultimate “Army Dreamers” is a lamentation in the form of a waltz, sung from the viewpoint of a mother who’s lost her son in military maneuvers. Here, the samples of gun cocks add a percussive and forbidding element to the arrangement. The sound is restrained but menacing when coupled with the shouts of a commander in the background. Plus, “Army Dreamers” is one of the more political songs in Bush’s repertoire, though situating it inside a personal narrative keeps it from becoming polemical.

The album’s closer, “Breathing”, is a more overtly political song. It was Bush’s crowning achievement at the time, a realization of everything that had led her to this point. The song is told from a fetus’s perspective terrified of being born into a post-apocalyptic world: “I’ve been out before / But this time, it’s much safer in”. Bush plays on the words “fallout” and the rhythmic repetition of breathing—“out-in, out-in”—throughout.

Synthesizer pads and a fretless bass build to a middle section in which sonic textures take precedence over lyrical content, as Bush’s vocals fade to a false ending at the halfway mark. Ominous, atmospheric tones play over a spoken-word middle section describing the flash of a nuclear bomb. The male voice is chilling in its dispassionate delivery, and the bass comes to the foreground once again in a slow march to the finish as the song reaches its final dramatic crescendo. Here, Bush’s vocals, which admittedly can be grating at times, perfectly match the desperation of the lyrics. “Oh, leave me something to breathe!” she cries, in a terrifying contrast to Roy Harper’s monotone backing vocals (“What are we going to do without / We are all going to die without”).

“Breathing” is a full opera in five-and-a-half minutes, written, scored, arranged, and performed by an artist growing into herself and beginning to realize her full potential. It’s a fitting ending for Never for Ever, an album that sees Bush, only 23 years old at the time, leaving behind her ’70s juvenilia. At the turn of the 1980s, she was poised to scale new heights with her music, some of which would define the decade to come.