As age sets in, a lot of the thrill of new music is in hearing the rejuvenation and reinvention of tropes and approaches that one perhaps thought too familiar to contain fresh excitement. Evan Patterson’s latest album under his Jane Jayle monicker apparently commenced as an instrumental tribute to Iggy Pop. Substantial input from Ben Chisholm as collaborator and producer, coupled with Patterson’s willingness to experiment, has created a result extracting mood and emotion from the “Berlin moment” of the late 1970s and giving it a complete overhaul and renovation.

There’s a remorselessness about the record, with only the briefest of relief amid a stygian post-punk swirl of dark sound. Album opener “A Cold Wind” is a pristine opener sitting somewhere between Tom Waits/Nick Cave torch song and Ultravox-style 1980s synthpop. Synthesized drones worm forward then drop dead, a steady drum rhythm circles, quavering high notes scratch at the chalkboard backdrop, while Patterson unfolds a gothic love song of vampiric resurrection and longing. The song’s movement, it’s build to a theatrical peak in which the loops push onward, and up-up-up mirrors the album’s forward motion in which there are no dead-end detours, no repetitions.

Twice, across the album, there are instrumentals that, in lesser hands, might serve as interludes. Instead, both “Synthetic Prison” and “The Last Drive” are a ceding of the spotlight from vocalist to producer, the former drinks from the same well as “A Cold Wind” while the latter builds boxing punchbag drum rhythms around a sternly hammered piano as data streams clatter through the background. Neither is gentle or tangential, and they don’t have the feel of reprises or introductory elements for other songs. Chisholm has engineered a coherent sonic vision that Patterson might inhabit but never dominates. It’s a visible partnership of equals — a rare moment where two egos neither overwhelm one another nor play too politely.

The front-end of this juggernaut is so powerful. “Don’t Blame the Rain” dances like a malfunctioning robot jester — it feels like either a mutant disco or a future assassin chase sequence — leading to a spring-loaded drum break that pogos heavily. Everything feels compressed and drowned, a druggy film scene where sensation overload sense until a moment of clarity briefly pulls everything into sober focus. “The River Spree” echoes “The Passenger” in its speeding combination of slurred impressions and pin-sharp travelogue detail. At one point, it grinds the listener across a gravel driveway, before hopping back into its shadowy journey and encounters with characters of hidden motivation.

“Broken glasses and a dead phone, a torn sheet of paper on my tongue. Berlin, I’m out here on my own,” Patterson recorded his lyrics direct into a phone while touring, which gives so many lines an electric realness amid their gorgeous poetry. That is true across the record — for example, “From Louisville”—the overwhelming sense of logging brief images and experiences while moving through places one doesn’t live and where one won’t stay long enough to learn names or specifics.

Beyond that, every song has something that distinguishes it or sends sparks into the ears. “Making Friends” twinkles a firestorm of high notes then pushes into a taxi cab encounter at half-past three in the morning, which devolves into an abduction based on loneliness and longing. “Guntime” is all grim marching and growling tank tracks then flips into a barstool cabaret over a slave-driver beat.

“Blueberries” drives further into the dark with drums battered at the bottom of a well and a metallic guitar spattering the track. One of the latter’s neatest touches is the gradual appearance of an android mirror — a gradual dehumanization of the voice also reflected in the way the words themselves move beyond human comprehension. “I Need You” starts like a drummer sound-checking with single ricochets smashed home before a jittery tinkling on the highest ivories of a piano begins to tap back-forth while the song ebbs and surges.

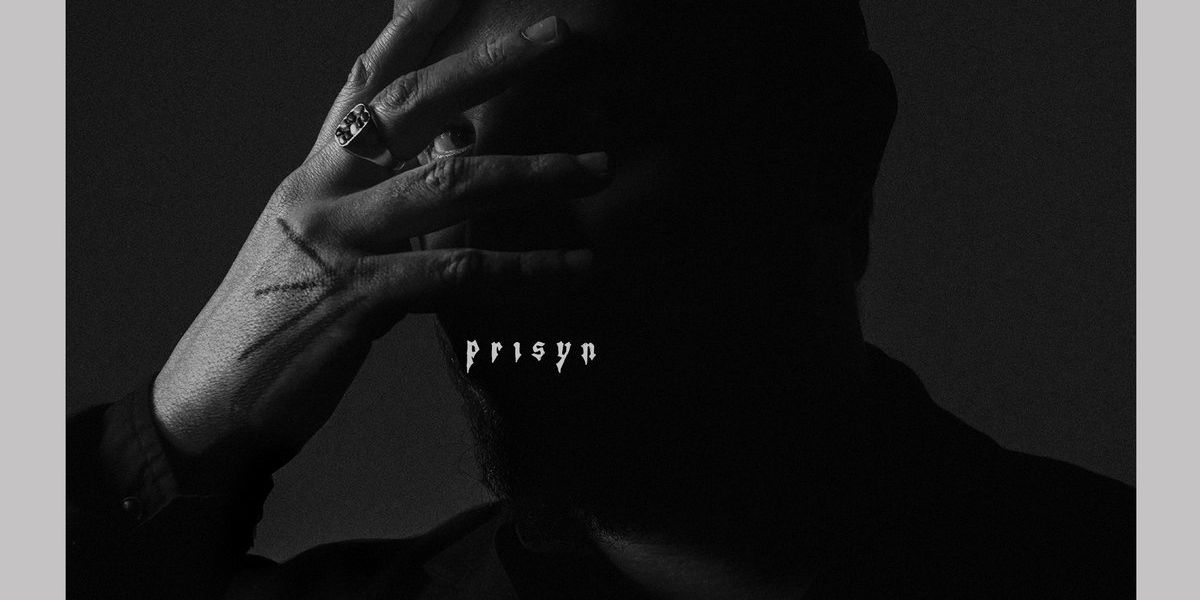

One of Prisyn‘s finest qualities is that it sticks to a precise ten tracks, no filler, no needless privileging of quantity over requirement. The only time I was tripped up came on the closer, “From Louisville”, and is entirely my bad. There’s a break that called to mind the “Chirpy Burby Cheap Sheep” episode of classic comedy Father Ted (listen to the baaing sheep iteration of the series theme tune). It pulled me out of what is otherwise a quality outro in which choral chants decorate drums that drag like a clubfoot over concrete.

Musically, Chisholm has created a gloriously paranoiac urban dystopia that fizzes with ideas and innovation. Patterson meanwhile dwells on the space between the pleasures of live touring — there are no cathartic communions with audiences, no enthusiastic companionship, no eye-opening discoveries. It’s to Patterson’s immense credit that this diary of exhausted, perilous, and lonely anonymity feels so thrilling. It felt like reading Get in the Van, Henry Rollins’ account of touring with Black Flag: the artist, try as they might to relay the grueling nature of touring, can’t help but also share the strange alchemical magic that keeps them on the road, tempting them on dark drives to find the unknown out there.