Posted: by The Alt Editing Staff

I hadn’t yet watched Blue Velvet when I first moved to Wilmington, North Carolina, the city where it was filmed. I would often walk by the apartment complex from the movie, which has now collected roses, candles, letters, and other Lynchian memorabilia. The bar, where my favorite line of all time comes from (HEINEKEN?!) hosts blues jams every week, serves beer from a styrofoam cooler, and has often served as a backdrop for fond memories with some of my closest friends. Being surrounded by the familiar places from his movies felt lucky while I worked on writing poetry and prose during my graduate program. Blue Velvet is not my favorite film by Lynch, but it does one of my favorite things he’s capable of, which is to combine the weird and mundane, the beautiful with the hauntingness of being alive. David Lynch gave a voice to people like Laura Palmer, who was abused, lost, and in pain, and amplified it rather than using her as a plot device. He gave us full, vibrant characters and pulled back the red curtains to small towns and their proof of existence. David Lynch will be missed sorely by viewers and artists alike and the scar from this loss is felt widely—but like he believed, he exists somewhere among the stars on a different plane. To honor and remember David Lynch is to give yourself wholly to the pursuit of trying new things in your art, to keep learning and experimenting, and to worry less about the darkness but rather, be surprised by it. We can embrace it, and we should—it might just be strange and wonderful. —Ryleigh Wann @wannderfullll

A few years ago, I was reading Peter Levenda’s The Dark Lord, which holds a magnifying glass to occult ideas like “the mauve zone” and “the nightside of the tree of life”—and it seemed like every other page would cause a robin in my head to start squawking “that’s like Twin Peaks!” It wasn’t until the start of this past year that I began to throw most of my free time into researching the occult (something Peaks co-creator Mark Frost seems to have an interest in) with an eye towards Twin Peaks—immersing myself in the strange worlds that Lynch taps into in all his films, rewatching them and their corresponding documentaries, and restarting a daily meditation practice after reading Catching The Big Fish and Lynch on Lynch. This was not necessarily to “understand” Twin Peaks, but to add another layer to how I watch the show (which, based on Lynch’s comments on such analysis attempts, he probably would have absolutely abhorred, so I am truly sorry for that). But, it’s also the nature of the art he creates to entice you to investigate a mystery, going down whatever rabbit (or ear) hole that entrances you and turns you into Frank Booth watching Ben lip-sync to Roy Orbison in that impossible-to-forget scene.

This is all to say I’ve been thinking a lot about David Lynch and his work the past year, not that it’s really equipped me to say anything coherent or thoughtful at the news of his passing. It doesn’t need to be said that his movies are surreal, dreamlike clashes of light and dark—incursions into this world from the other. People know these things. It’s more the reactions those clashes create in you when you watch his films, causing you to perceive the everyday world around you to be as surreal as what Lynch shows on screen. It’s always been those clashes (or to use the alchemical phrase, “conjunctions of opposites”) that interested me in Lynch’s work, and he put that notion best himself in Lynch on Lynch, saying: “Well, we all have at least two sides. One of the things I’ve heard is that our trip through life is to gain divine mind through knowledge and experience of combined opposites. And that’s our trip. The world we live in is a world of opposites. And to reconcile those two opposing things is the trick.” Rest in peace. — Aaron Eisenreich @slobboyreject

When I began making my way through Lynch’s work, I was hesitant to start Twin Peaks. I often think about death, which makes television difficult for me. Even the worst movie is only two or three hours of my life, which I find a fair trade for distraction, but a television show quickly becomes a real investment of time. At 45 minutes a pop, including the 1-hour 53-minute pilot, the first season comes in at seven hours. That’s seven hours that I could be doing chores, visiting family, creating art. And the second season comes in at over 17 hours with 22 episodes. Then there’s the movie and the 2018 reboot and what if I got into a car crash and died before I finished that!? Maybe I should just watch Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me, and I could get by without watching the show. But in January 2024, though I’d be losing a day of my life in the first two seasons alone, I proceeded to knock out the entirety of Twin Peaks. More than that, I had become, as fans in the 90s called themselves, a Peak Freak.

I find it embarrassing to admit, but I didn’t become a fan of Twin Peaks because of the atmosphere, mystery, the masterful way it unfolded Laura Palmer’s secret double life, or even how it changed television by showing the emotional impact of a missing girl. I became a fan of Special Agent Dale Cooper, the dedicated, good-natured, intuitive FBI Agent. I found him out of place as the protagonist of a show that’s been lauded as the prototype for the modern television show. I’d been raised in a world of anti-heroes: Tony Soprano, Dexter Morgan, Walter White. People doing morally reprehensible things for the entertainment of millions. Should the protagonist keep the trappings of the traditional TV hero, such as an honor code or the profession of detective, they bear their burden like crosses. Characters aren’t good and happy. In fact, they rarely seem to be either.

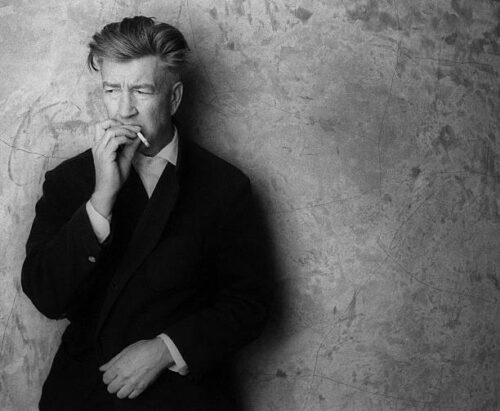

Compared to these characters, Dale Cooper would be more at home in a sitcom rather than solving a murder case. Cooper’s goofy. He’s downright whimsical, really. He repeats the names of local flora and fauna with childlike wonder. He often appears to think more of coffee and donuts than his job. He’s religious, often bringing up the Dahli Llama, and keeping a seemingly devout meditation practice. The only thing setting him apart from the role of an overly friendly and socially oblivious sitcom neighbor is his clean black suit, immaculate hair, and his competence as a detective. In many ways, he resembled his creator, David Lynch, a parallel that has no doubt been noticed by fans and critics.

Watching as this strange, slightly dorky man navigated the shadowy edges of Twin Peaks with grace and determination awoke something childlike in me. I found myself thinking, “Oh, I want to be like that guy.” Only this wasn’t a bullet-proof superhero or a feather-haired twink with a laser sword and telekinesis. He was just a man. And in some ways, I started acting like him. I started taking my coffee black, relishing the contrast of bitter and whatever sweet pastry I thought Cooper would have chosen. Though Cooper didn’t smoke, Lynch did, and I did that quite regularly, picking up a pack of American Spirits, ignoring the harsh gray flavor, and instead focusing on how the chemicals felt incandescent in my bloodstream. And, of course, like Cooper and Lynch, I started to fall in love with the sleepy little town of Twin Peaks, and Angelo Badalmanti’s notes ascending and descending as if traversing up and down the mountains.

The Red Room is Lynch at his best—the otherworldliness, bordering on obscene, permeates the air, making its red velvet curtains appear to breathe. Here, we find all the elements that have led Lynch to be called a visionary. Here, I also wonder what we mean when we say that word. Is this a vision he has crafted or rather stumbled upon? Lynch had said in multiple interviews that he didn’t create any of these ideas; he merely found them in the realm of “pure consciousness”. In this way, Lynch was a visionary in the same way that the Oracle of Delphi was a visionary. Had Lynch been born in another time, it’s not impossible to see him as a seer, offering a small gathering of pre-historic humans a look into the world of dreams through fable and song told over the flickering light of a fire. In some ways, Lynch still found himself behind the flames, telling stories as shadows danced upon his face, playing songs as the wind sang through the branches of the pines. — Jake Cessna @jakecessna

The Alternative is ad-free and 100% supported by our readers. If you’d like to help us produce more content and promote more great new music, please consider donating to our Patreon page, which also allows you to receive sweet perks like free albums and The Alternative merch.