From 1939 to 1944, writer-director-producer Preston Sturges seemed nearly incapable of a false step. He shocked Hollywood with the success of his first film as director, The Great McGinty (made in 1939 and released in 1940), by combining these three, generally distinct roles, creating a box-office smash, and winning an Academy Award for the screenplay. Jealousy soon set in. Hollywood films were corporate affairs. It typically wasn’t the case that a single person filled any of those three roles, much less simultaneously and solely held all three. Writing occurred in stages, each stage having a different writer taking his or her approach. Even directorial chores were often shared.

This is the assembly-line nature of the classic Hollywood film and it is partially responsible for the distilled, refined, utterly smooth productions that emanated from these cinematic factories. A Hollywood film ticks along like a well-oiled machine because that is what it is. No one cares to see how the sausage gets made; audiences are interested only in the confection that results. Narrative cohesion, cohesion of writerly tone is exchanged for cohesion of image, a welcome and familiar formal cohesion. Films by committee work because, at base, films are a business.

In a sense, Sturges is rather comfortable with allowing audiences to see the sausage being made. There is not so much a formula to Sturges’ design as there is a kind of idiosyncratic rhythm that pervades each film and gives it its character. In

The Lady Eve (1941) we might, only somewhat whimsically, notate that rhythm as SSP: snark, sincerity, pratfall. The worldly-wise cynicism of Sturges’ ebullient wit gives way to a slight tugging at the heartstrings (redeemed in advance by the badinage) and is then punctuated with some bit of physical comedy. Hollywood as it generally ran couldn’t do it without becoming cloying: the formula works because it is so blatantly a formula that it defies the very nature of formula (which is to go unnoticed).

But perhaps that is the lesson we are to learn from

The Lady Eve. We live out formulae so preposterous that we accept them as idiosyncratic to our experience. How long can we possibly do the “A meets B and falls in love” story? As long as there are As and Bs and love and falling, presumably. The experience is ever-the-same and ever-new. We say that dishonesty is the enemy of love. Of course, that’s not true. It may be the enemy of the longevity of relationships, but it is hardly the enemy of love.

We lie to get others to fall in love with us all the time. We lie to ourselves while lying. We don’t even know we’re doing it. We just think we are saying what one says, we are relying on formulae that convey our feelings. Formulae are the lies we use to understand the unutterable. I’m vulnerable; but I’m not the kind of vulnerable I project to you. My wit is somehow more profound when I speak to you.

(Criterion)

It’s all performance, artifice. Truth in theater is always a partial lie. Of course, my way of loving is not identical to yours and yet we go through the same narrative strains again and again. What The Lady Eve manages to demonstrate is that somewhere within the convolution of deception (self-deception included) lies a truth that persists all the same.

Charles Pike (Henry Fonda) is the heir to a brewery fortune. His father (Eugene Pallette) is the creator of Pike’s Ale, “The Ale that Won for Yale.” Charles prefers studying snakes during expeditions to South America, accompanied by his worthy guardian but inept valet, Muggsy (William Demarest). His insistence on the term “ophiologist” may be intended as a sly indicator that we are dealing with an oaf.

On the voyage home from one such expedition, with a small serpent in tow, Pike boards a luxury liner, setting all the marriageable young women abuzz, alongside a healthy dose of ambitious mothers, fortune seekers, and unmarriageable women. As he climbs the ladder to the ship, a young woman mischievously drops a partially eaten apple on his head just to see if she can get a reaction.

That woman is Jean Harrington (Barbara Stanwyck), a con artist in league with her amusingly corrupt father, “Colonel” Harrington (Charles Coburn), and their card sharp accomplice Gerald (Melville Cooper). They are oddly decorous in their iniquity. Her father reproves his daughter’s assault via fruit with the adage: “Let us be crooked but never common.” Their goal is to fleece Charles for all they can get from him. He is a mug, in their vernacular.

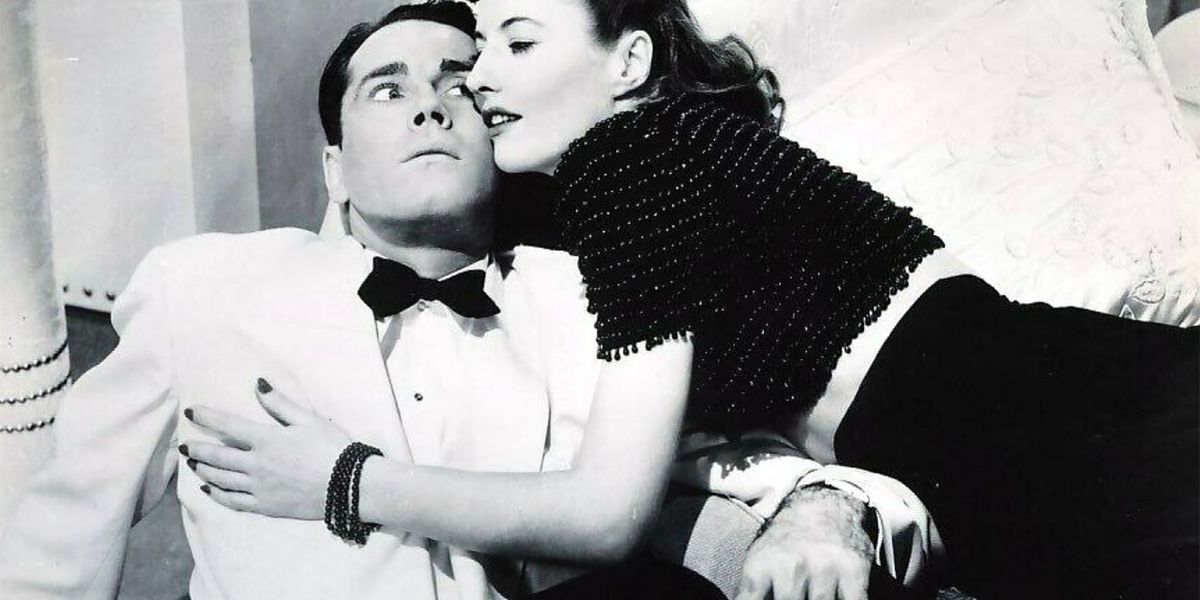

Jean observes the hopelessly oblivious Charles in the dining room via her compact mirror, narrating the various attempts the eligible bachelorettes around him make to grab his attention, amused by his lack of observation and benign indifference. Her approach is more direct. She trips him as he passes by and then scolds him for having broken the heel of her shoe. And so the seduction begins and quickly escalates.

But as Jean plies Charles with her wiles, his utter susceptibility to her charms becomes charming in its own right. She falls under the spell of her own attempts to mesmerize him. He really is a mug—to the very core. He is disarming in his total lack of perception.

Charles soon proposes, completely unaware that Jean has to continually protect him from her father’s attempts to cheat him. Charles leads Jean to the front deck of the ship and launches into his proposal. He claims he didn’t just see her first mere days ago, she seems “to go way back” into his distant imaginings. It’s drivel but it seems sincere and she likes it. Jean realizes he is in love with her and she is in love with him and she decides to take the reins; after all he’s a mug and besides “a moonlit deck is a woman’s business office.”

(Criterion)

Jean’s father is concerned. “A mug is a mug in everything,” he avers. What happens when Charles discovers her grifting. These moral types can be narrow-minded about such things. And he does find out, before she can tell him. And he is rather narrow-minded about it, throwing her over without waiting for explanation, without taking seriously her genuine feelings for him. So, she soon plots revenge and shows up at a dinner party his family is giving, wearing no disguise save for a rather thin British accent and the ridiculous moniker “Lady Eve Sidwich”. Because, why not? He’s a mug. He believes this must be a different woman because he understands psychology. If this were Jean playing a trick, she would have made more of an attempt to disguise her features. The fact that she looks exactly the same proves this is another woman.

So, it starts all over again. It’s that same formula again: SSP. He falls for her again, figuratively and literally—launching himself over a couch while Muggsy falls into a bush as they confer as to whether or not this is the same “girl”—inaudibly through glass. It’s preposterous, of course. “That couch has been there fifteen years and no one has fallen over it,” the father roars. “Well, now the ice is broken,” “Eve” quips. Charles proposes again, using that same line about knowing her in some far-off distance of forest glades and converging lines. This time they marry and Jean as “Eve” exacts her revenge, she pulls through on her grift. And just like last time, she falls in love with him all over again while doing so.

At one point Jean, not knowing that Charles already knows she is a con artist and preparing him for that bit of truth (which isn’t really truth, after all), tells him that no good person is as good as they seem and no bad person as bad. That may seem like just another performative gesture, another blurring of the line between the truth as such and the truth as Jean needs it to be. And I suppose it is. Love is performative. It is an act in both relevant senses of the term: it is something I do and something I feign. Jean’s act of love is only communicated by going through the motions of love. She didn’t invent love and she didn’t invent its terms. The fact that it has terms, social cues and expectations, demonstrates its inherent falsity.

But it is a falsity with a truth at its core, even if (maybe especially because) that truth cannot be paraphrased or summarized or even communicated outside of the theatrical language that transmits it, that shapes it, that becomes a condition of its possibility. Charles is shown to be just as false. The audience, alongside Jean, is meant to be outraged, at first, by Charles’ proposal to “Eve”, employing the same ridiculous doggerel that he used on the ship.

What had seemed a clumsy attempt at poetic flight turns out to be a rehearsed gambit, a well-worn formula to describe feelings he has probably never had—at least not on those terms. But then the horse keeps nuzzling the back of his head, interrupting his speech. And we, and Jean, find it all charming again. We don’t love in terms, we clumsily and inadequately communicate love in those terms and in the act of communication we fall into the act of love.

At the center of all that mild fakery (and Charles is just as given to fakery as Jean is, he just isn’t as good at it), resides an honest deception. In repeating the formulas, we enact the movements of love. In lying to our beloved and in lying to ourselves, we recapitulate the truth of love. Love is a game and there’s no winning it. You just keep playing.

Criterion Collection has released a blu-ray edition of Preston Sturges’s witty, screwball masterpiece, The Lady Eve. The film is gorgeously presented here in a crisp restoration and the edition is replete with extras celebrating this remarkable film.

A 2001 audio commentary by film scholar Marian Keane is coupled with a 2001 introduction by director-writer Peter Bogdanovich. There is also a new roundtable discussion led by Sturges’ son Tom, a video essay by critic David Cairns, a feature on the costume designs by the renowned Edith Head, and a radio version of the film starring Stanwyck and Ray Milland.

The insert features an intriguing 1946 profile of the director right at the point when his career was about to go into decline (although no one could have guessed it at the time).