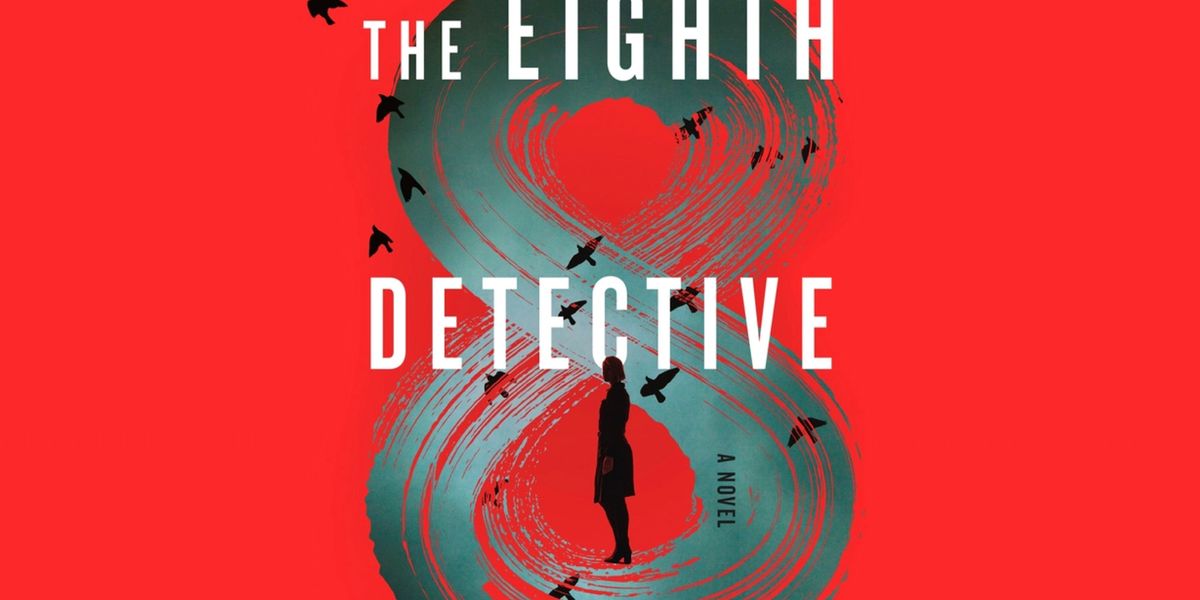

Alex Pavesi’s debut novel, The Eighth Detective, posits mathematical rules defining ‘detective fiction’ and serves up a fresh and multi-layered homage to that well-worn genre.

Pavesi, who has a Ph.D. in mathematics, creates a protagonist, Grant McAllister, who is also a mathematician. In 1937, McAllister published a research paper entitled The Permutations of Detective Fiction, examining the mathematical structure of all murder mysteries. Then, in the ’40s, he wrote and self-published a collection of seven stories designed to embody these factorial permutations. When McAllister retired, he moved from Edinburgh to a Mediterranean island and now Julia Hart, who we are told is an editor at a publishing house intending to republish this collection, has arrived on the island to spend a few days discussing these stories with their author.

In Pavesi’s novel, seven of the chapters present these detective stories, each with a different detective and each followed by a chapter consisting of Julia’s analysis and discussion of the preceding story with her host. This structure is clever, as it allows us to read the stories and then to experience Julia’s many questions about them and her analysis of the application of McAllister’s mathematical rules. In this way, readers can vicariously observe the experience that writers are apt to endure, an editor unearthing a story’s inconsistencies of which, alas, the author had not been aware and cannot explain.

The opportunity for such meta-mathematical analysis doesn’t end there. Julia’s conversations, spread over several idyllic days on the island, seem to flummox her elderly host, who confesses his bad memory after the decades-long period since the stories were written. These conversations soon lead her to believe that another mystery altogether is emerging, with Julia becoming, in effect, the eighth detective.

As to the ‘mathematical rules’ of detective fiction, the host draws a Venn diagram consisting of four circles within a larger circle denoting ‘murder mysteries’: S (suspects, at least two), V (victims, at least one), D (detectives, at least one) and K (killers, at least one). He explains that “K must be a subset of S” which is just a formalized way of saying that the killer must be one of the suspects. He goes on to note that in standard cases of detective fiction the four circles are separate, but in aberrant cases the circles can overlap so that, say, the detective can be the killer. He concludes:

There are only four components to a murder mystery, so

the number of permutations is relatively small. We can

calculate and list every single one of them. Every possible

structure. That’s what these stories were meant to

explore.

This application of set theory is rudimentary and obvious, although Julia mentions the absence of ‘clues’ from the analysis and her host responds excitedly that yes, clues are not essential: “[g]o through any murder mystery and delete all the clues; you’ll still have a murder mystery.” This statement is presumably meant to display a surprising consequence of McAllister’s thesis, showing that it is indeed a meaningful theory, but this point is odd because clues are simply what happens in the story — the timing of one S’s card game at his club, the fact that another S left her scarf behind in the maid’s quarters, whatever.

Anything that occurs can be a clue; a story without clues is a story in which nothing happens, and so there is nothing against which to test alibis. We’re going to need a bigger Venn.

The chapters of The Eighth Detective containing the conversations between Julia and her host are the most interesting, as this is where it dawns on Julia and the reader that there may indeed be another and quite different game afoot. The sense that something is amiss slowly becomes palpable.

This frame-tale is what makes the book engaging and interesting because the seven detective stories themselves, although set in a wide array of inventive settings and circumstances, feel lengthy and over-stuffed with characters, clues and alibis – possibly because Pavesi views his job as only to craft stories that embody the elementary mathematical rules. The detective-story writing is unembellished and straightforward; Pavesi’s intent may have been to present stories in the stripped-down style of 1940s-era detective fiction.

It’s an open question as to the value of worrying about how strictly to define a genre. Maybe we simply know it when we see it; maybe such pigeon-holing doesn’t matter. Still, the value of The Eighth Detective is found in its inventive premise and the layered and meta-friendly structure within which Pavesi’s protagonist posits the mathematical permutations of ‘detective fiction’.

Murder most factorial.