Posted: by The Editor

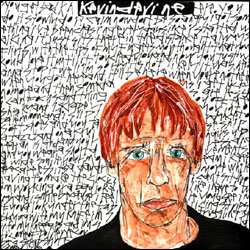

In the late ’90s, bleeding into the early 2000s, Kevin Devine was in a Long Island emo band called Miracle of 86. Not Long Island emo in the sense of The Movielife, Taking Back Sunday, or Glassjaw–the band’s 2000 self-titled debut owed a heavy debt to the emo standard-bearers who came immediately before them. The start-and-stop riffs were pure Mineral, and Devine’s ragged vocal performance could’ve been pulled straight off 30º Everywhere. A little while after that record was released, Devine began collecting songs to release under his own name, songs some of the other members of the band didn’t think would fit the vibe of Miracle of 86. These songs were largely political, blending left-wing themes with tales of Devine’s own struggles with dependency. He compiled them into a solo LP called Circle Gets the Square, which dropped quietly on March 19, 2002.

The following year Miracle of 86 released their second and better-known record, the one Devine himself calls “the Miracle of 86 record,” Every Famous Last Word. The album expanded their sound, pushing past the boundaries of midwest emo to incorporate elements of indie rock, pop rock, and even some alt-country. It’d be their last record, and would, in time, become something of a cult classic.

That same year, only months later, Devine released his second solo record on Triple Crown Records. Make the Clocks Move fell somewhere between the dusty folk of Circle Takes the Square and the full-bodied indie rock of Every Famous Last Word, mixing the sounds of his previous two releases. In the twenty years since his sophomore album dropped, Devine’s released eight other studio LPs under his own name, along with two live-in-studio releases, one acoustic re-imagining, and numerous covers albums. None of the eight albums of original material that followed Make the Clocks Move exist in the same space as that record; 2006’s Put Your Ghost to Rest (possibly Devine’s opus) comes the closest, a collection of taut indie folk tracks that are more richly textured than anything on Make the Clocks Move, that are more layered and intricate. Produced by Rob Schnapf, who manned the boards for Devine’s hero Elliott Smith’s late ’90s run, it’s cleaner than Make the Clocks Move (produced by ex-Miracle of 86 bandmates Mike Skinner and Chris Bracco, who also play on the LP); while, on a song-by-song basis, it’s the stronger record, there’s something charming, even comforting in the rawness of Devine’s second record. It feels like a songwriter only beginning to come into his own, one willing–maybe even hoping–to make mistakes.

I saw Kevin Devine on his co-headlining tour with The New Amsterdams, earlier this year, where he played Make the Clocks Move all the way through. He joked, before he played relatively deep cut “Country Sky Glow,” that it was his attempt at a country song, which in a live context gets filled out beyond its in-studio frame with slide guitar–many of Devine’s songs, throughout his catalog, get periodic updates in live settings. When Devine plays “Ballgame” live, he tends to add an entire new verse, for example. “I went to see Bob Dylan when I was 18,” Devine tells me, and his band would launch into songs Devine didn’t know before he realized they were reimaginings of classic Dylan hits. (“Is this a fucking zydeco take on ‘Masters of War’?” Devine recalls asking himself.) So this sort of living songwriting places him in classic folk lineage–but it goes beyond that, he says: “Growing up with MTV, you’d see these bands–Nirvana, REM–taking these raucous songs and softening them down.” He points to Counting Crows, too, who’d switch up the lyrics and even the riffs of their biggest hits for television performances. It helped him teach himself that “these songs are breathable and fluid. They don’t have to be rigid.”

This habit of Devine’s makes the original album an interesting listen. In conversation Devine notes that he’s come a long way from “that 23-year-old kid who was drunk every session and listened to too much Saddle Creek,” and that’s even clear from comparing the songwriting on Make the Clocks Move and any of his subsequent records. The lines between the personal songs and the political ones began to blur further–it was only the beginning of his “outward-looking songwriting,” after all–and the structures got less conventional; he’d play more with dynamics and texture on later records (never more than on 2009’s Brother’s Blood, the runaway fan favorite and perhaps not coincidentally his longest by far). That’s what makes his second solo album such a marvel, though, too. “It felt like a jump happened” when he started working on the songs that’d become Make the Clocks Move because, compared to what he’d put out with Miracle of 86 or on Circle Takes the Square, “the songs were better.”

“Ballgame,” as an opener, is the perfect introduction to Devine’s music, though it’s far from a conventional track one; at over five minutes, it’s by far the longest song on the record, and it’s a true solo track, no bass or percussion or piano, just his voice and his guitar. In his classic fashion, he lambasts himself for “drinking alone” and for making himself “really fucking sad” while “my shit’s about as small as it could be” when other people have serious problems, like his brother’s “20-year-old friend” who’s going off to war while Devine sits around and drinks. It’s a situation most 20-somethings have found themselves in: miserable and knowing how to dig themselves out of the situation they’ve gotten themselves in but too wrapped in self-pity to do anything. He puts it more poetically:

I’m selfish enough to wanna get better

but I’m backwards enough not to take any steps to get there

and when you realize it’s a pattern and not a phase

it’s what you’ve become and it’s what you will stay

that’s ballgame.

Songs like “Wolf’s Mouth” and “You’re My Incentive” are looser than the sorts of stuff he’d do later in his career, and there’s a levity to “Not Over You Yet” and “People Are So Fickle” that he’d rarely recapture. A lot of it probably comes down to Devine’s delivery; his voice now is feathery and smooth, and he can contort it into a fluttering falsetto or a growl at the drop of a dime. He sounds boyish on Make the Clocks Move, and he hasn’t quite mastered how to control it yet; Devine himself says, despite his appreciation for Skinner and Bracco’s production and taking pride in his lyricism, “I can’t really listen to that record with the way I’m singing on it.” But, again, Devine started in an emo band. He treats his voice like an instrument now on songs like “She Can See Me,” twisting it to fit in with the guitars cradling it; on Make the Clocks Move he sings like every song might be his last–at the time, he thought it could’ve been. His voice starts to shake towards the of highlight “Longer That I’m Out Here,” and it makes each successive repetition of the title phrase hit harder; he’s audibly straining through the bridge of “Not Over You Yet,” grounding a song that otherwise might feel like a half-ironic lost love song (“you were always cute / but god damn you got hot“). The second half of “Noose Dressed Like a Necklace” is one of Devine’s most impassioned performances of his whole career as he sneers at the Iraq War and the drudgery of proletarian life; he yelps wordlessly like a banshee as the full band comes in before rasping his way through the record’s whole MO: “I know it seems dramatic / but I treat it like a crisis.” And that, of course, is part of the appeal. When you’re 23, every goddamn inconvenience is a crisis.

When I ask Devine if revisiting the album to prepare for the tour renewed his appreciation for any of the songs, he chooses some left-field picks: “Whistling Dixie,” “Marie,” “Country Sky Glow.” It is easy to see why; despite the self-deprecating joke he cracked about slotting “two country dirges” together, “Marie” and especially “Country Sky Glow” take on new life in front of a crowd. They were highlights, for sure. Probably the best part of the night, though, was when Devine launched into that unrecorded verse at the end of “Ballgame.” Even though it’s nowhere to be found on the recorded song, the whole room knew the words.

––

Zac Djamoos | @gr8whitebison

The Alternative is ad-free and 100% supported by our readers. If you’d like to help us produce more content and promote more great new music, please consider donating to our Patreon page, which also allows you to receive sweet perks like free albums and The Alternative merch.