Rebecca Dinerstein Knight’s second novel, Hex, is a portrait of ennui. The character Nell Barbar is a former doctoral student in botany from Columbia University. She is expelled from the program after a lab mate dies of accidental poisoning. Nell’s decentering forces her to examine and redefine her life.

She is part of a small character group, six total, whose interconnected lives drive Hex‘s plot. Whereas the novel demonstrates moments of emotional intensity and humor, Hex‘s proclivity towards toxicity is overburdening.

Hex finds Nell untethering from her responsibilities, the newfound lack directly informing her dejection. Her life before expulsion wasn’t noteworthy either; her research on oak trees is boring, her family is distant, and she’s ending a loveless relationship with Tom. She sinks into her discontent with snarkiness and nihilism, the blueprint for intriguing character development — but that doesn’t happen.

Whereas the novel progresses, Nell’s awareness does not. She dwells in an arrested emotional and physical space: she never exhibits growth. She promises, “I am going to mire in it until I am cooked. Then, you know, I’ll taste great” (69). But the greatness is never actualized. Nell maintains turgidity, admitting “I am not living, or feeling alive” (178). Her languor is so overpowering that it burdens the entire narrative. She becomes repellent. She is in crisis, and readers will wonder why her friends and family don’t support her. But then, unfortunately, her peers are revealed as intensely loathsome.

Hex‘s characters socially and professionally circle each other, with academia serving as their hub. They are narcissistic, and their flaws are more problematic than endearing. Tom, for example, is a selfish rich boy who misrepresents his unicorn fandom as research. Nell is aware of this, yet she apathetically accepts “people who need to earn a living and people who get by being wealth-adjacent” (85).

Tom has an affair with Joan, Nell’s academic advisor and object of her obsession. Here, Dinerstein Knight misses the opportunity to consider queer longing and obsession. Instead, she casts Joan as a symbol of toxicity. Joan is a distinguished academic yet fails to maintain healthy social relationships. She constantly treats Nell with disdain, even cruelty, swapping compliments for comments “so rude, [they are] in the name of balance” (96).

Hex is written as a journal in the second-person narrative, therefore Nell’s love for Joan is fully experiential. But Joan’s inability to respond to Nell with an iota of humanity is the novel’s truest calamity.

Joan serves as the overachieving academic stereotype, one who embraces misanthropy to focus on her career. In that way, Joan is an overused cliché and the personification of anti-intellectualism. Her inability to enact amiability and penchant for malevolence negates her intelligence. She sleeps with her students while bullying others, behavior that is both appalling and unrealistic.

In contrast, Mishti is a motivated student, her confidence and glamour radiate. Inexplicably, she sleeps with Joan’s husband, Barry. He is an ineffectual loser who uses his family’s wealth to secure the prestigious, albeit useless, role of Associate Director of Columbia Undergraduate Residence Halls. But even before the adultery, Joan despises Mitshi for her intellect and passion, misdirecting her anger onto Mishti’s many bracelets. At no point does Hex portray smart women as functional or collegial. Readers will certainly disconnect from these obnoxious characters.

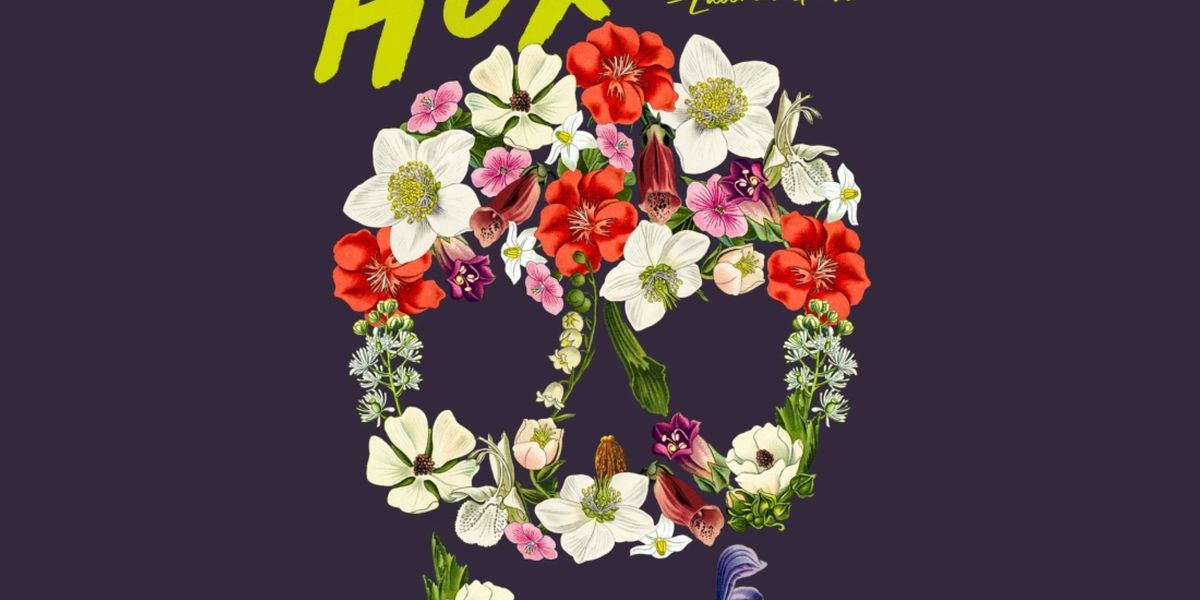

Hex‘s strongest writing captures botanical histories. Dinerstein Knight relies on alchemy and herbalism to contextualize Feverfew, Sassy Bark, and the Castor Bean’s complicated history as lethal and medicinal plants. More so, Aconitum, or Monkshood, is placed within a cultural context, with references “in Shasekishu, in Shakespeare, in Medea” (14). Like Castor Beans, Aconitum is toxic despite its beauty and healing properties. It is through botany that Dinerstein Knight defines the overlap between beauty and the abject.

For example, Nell turns “to botany like anybody because I found flowers terrifyingly attractive” (101). Her strive for beauty is based on science rather than aesthetics. Her research in toxins and antidotes encapsulates her belief that everyone should suffer then heal, an axiom reflected by her peer group. Hence, Tom and Mitshi’s self-absorption is intentional. Their presence is the manifestation of Nell’s search for beauty in spite of the evident venomousness. Joan is also supposed to personify this paradox, but her moments of beauty are eclipsed by her spitefulness.

With the beauty/abject paradox in mind, perhaps readers can forgive Dinerstein Knight’s penchant for grossness. In a chapter aptly titled “Boogers”, for example, Dinerstein Knight depicts Nell picking her nose and watching her trophies dry on the windowsill. Moreover, Nell’s nervous habit of picking food out from under her fingernail is discussed several times.

Although Hex‘s repulsiveness is conspicuous, its beauty is obscured. The flowers Nells grows are not enough to concretize Dinerstein Knight’s motif. Unfortunately, there is no equilibrium and Hex fails to beautify.