About a decade ago, three of us took advantage of MOMA’s free Fridays, wandering through some of the most amazing art that one could see in a single space. But, we were too busy giggling about Foghat to take it in fully. I’m not sure how or why, but one of us had brought up the idea of putting together an all-Foghat tribute band, Hogfat, that would only include one song in its set: an endless version of the 1975 Coors-and-a-Camaro classic “Slowride”. This led to further ideas. How about a Foghat cover band made up entirely of lumberjacks called Loghat? Or, perhaps one whose stage wear had to include wooden shoes called Cloghat? Maybe a quartet of the perpetually curious and surprised, known as Agoghat? This conversation, more than the fine examples of impressionism galore, has stayed with me.

So, just where did such a name come from, and why is it so funny? Experimental musician Phil Yost—whose two late 1960s Takoma LPs are as brilliant they are uncategorizable—titled his 1968 album Fog-hat Ramble. (I suppose fog could cover an area just like a hat.) However, Foghat’s original frontman, principle songwriter and guitarist “Lonesome” Dave Peverett, apparently insisted it was a real word, having spelled it out during a scrabble game. At least that’s what both drummer Roger Earl and original bassist Tony Stevens claim, the latter during an interview conducted in a hot tub.

While the name’s meaning or origins may have to remain something of a mystery, for now, three-fourths of the original band (Stevens, Earl, and Peverett) had chugged along as London-based blues-rock outfit Savoy Brown’s rhythm section for several years in the late 1960s. By the dawn of the 1970s, the three of them—alongside Savoy Brown’s only constant member, Kim Simmons—were a quartet. This line-up released the slightly harder-rocking Looking In in 1970. By now, Peverett was co-writer and lead vocalist, trading guitar solos with Simmons. You might argue this record was Foghat in all but name. You also might not.

Depending on who’s doing the telling, Peverett, Earl, and Stevens either quit or were fired after gigging behind the new album. Within a year, they’d found guitarist Rod Price, inked a deal with Warners’ subsidiary Bearsville Records, and released an album, 1972’s self-titled Foghat. Not only did this LP introduce a classic-rock radio staple—their wah-wah-influenced, proto-metal cover of Muddy Waters’ “I Just Want to Make Love to You”—but it also connected them to Bearsville engineer Nick Jameson, who mixed two of the album’s tracks.

Over the next two years (and three more records), Foghat barnstormed the US, throttling audiences with extended versions of “I Just Want to Love to You”, hamfisted takes on Big Joe Turner’s “Honey Hush”, and John Lee Hooker-inspired originals that aimed straight for the cheap seats. By 1973, they’d made the US home and churned out meat and potatoes rock that managed to capture the 1970s in a bottle. Their music was as harmless as it was inconsequential; it would blend just fine with cheap, seed-heavy reefer and Jack Daniels as it echoed out of mid-sized auditoriums across the country.

Design Face Eye by Geralt (Pixabay License /

Design Face Eye by Geralt (Pixabay License /

If ever there was a band whose essence could be distilled into a single song, it would be Foghat. It’s likely that even in 2020, one could drive from DC to California, setting the radio’s FM dial to nothing but the country’s endlessly generic sea of classic rock stations, and still hear “Slow Ride” at least 20 times. It’s hard to fathom that four records and Stevens’ departure even had to happen before they cut their masterpiece. It’s also pointless to remember much else that they did, now that the roach clips have long ago caked with rust. “Stone Blue” anybody? “Driving Wheel”? Foghat belongs to a lineage of well-intentioned 1970s rock that, like Grand Funk Railroad, exploded for a few years but has gone on not to matter much. That isn’t a criticism; it’s simply a statement of fact that places them with the majority of consistent major label sellers of the era. (There’s a reason most of their back catalog hasn’t been the subject of vinyl reissues.)

Yet, to understand Foghat’s stubborn place in classic rock history, one has to deal with their fifth LP, 1975’s Fool for the City. It’s also important to note that Stevens’ temporary replacement was none other than Nick Jameson, an American better known for his voice acting, as well as his role as Russian President Yuri Suvarov over several seasons of the TV show 24. Jameson’s attention to detail briefly elevated Foghat from mere low-common-denominator 1970s boogie. His sub-Larry Graham slap bass work on “Slow Ride” is part of the song’s perennial biker-festival cachet. Jameson produced and engineered the album and co-wrote the most forgettable track, the limp pseudo-soul song “Take It or Leave It”.

However, five of the other six tracks on this record, while certainly not in danger of elevating Foghat to the importance of peers such as Zeppelin, at least make a case for them. The title track—a song trading rural disgust with urban exuberance, not unlike the Velvets’ “Train Comin’ Round the Bend”—gave them a riff-driven show opener for the foreseeable future. Both “Save Your Loving (For Me)” and their cover of the Righteous Brothers’ “My Babe” are almost power-pop. The latter kept Hatfield and Medley’s harmonies and added a riff made for chasing bourbon with cheap beer on a ripped dive bar swivel stool. This is Foghat making its case for classic rock endurance without taking away an ounce of their sub-glam swagger. Jameson’s attention to tone gave Peverett and Price’s guitars an authority they never had before or since.

The album’s reigning example of this is their cover of Robert Johnson’s “Terraplane Blues”. Anyone coming to the blues via British rock bands could be forgiven for thinking Johnson must have been friends with all of these folks (perhaps even a songwriting contemporary), so often did the likes of Cream and the Stones snag his licks and reference his name. But for molten, riff-driven, cucumber-in-pants interpretations of the Delta, Foghat rules the roost here. With Peverett’s rhythm, not to mention his constant ecstatic whoops, and Rod Price’s languorous slide guitar gymnastics, they render this song—a figurative ode to infidelity with lots of auto references—heavy enough to make Jimmy Page take notes. They even add a minor-key bridge. This might be their best moment.

Oh, but then there’s “Slow Ride”. Jim O’Rourke once observed that due to the song’s length and constant repetition of the title, it goes from being a song about sex to a song about nothing. I like to think it becomes a song about a metaphysical slow ride, whatever that may be. Trimmed from its original eight-plus minutes to just over three, it became a massive hit, but a radio station today wouldn’t touch it without touching all of it. This means not only the opening kick drum and overdubbed booted stomp, Peverett’s riff, and Price’s whining slide, but also Jameson’s mid-song funk bass improv as Peverett exhorts on-the-spot declamations about “feelin’ good” and “liking” it.

He reels the band back in like a master fisherman with a Zebco 505 and a big-mouth bass on the line, matching the repeated phrase “you know the rhythm is right” to Price’s lick before they blast into the greasy stratosphere (where they grind out a single chord as Price rams the bottleneck up and down the guitar with the subtlety of a blow torch). Finally, the entire thing explodes in one last, post-ejaculatory “Slooooooow Riiiiiiide!!!!” This is rock and roll taking itself just serious enough to ride the bombast while being playful enough to make it all sound like a party.

“Slow Ride”, as it turns out, is a suite of sorts. No one ever needs to hear “Stairway to Heaven” or “Free Bird” again. “Slow Ride”, on the other hand, only feels better with age. Where “Stairway” chokes on its pretensions and “Free Bird” hangs itself on a rope made of wankery, “Slow Ride” injects itself into your DNA, its blues-metal descending riff a comfortable, broken-in cushion. For eight minutes, they managed a party anthem that now feels as crisp as aged-at-sea whiskey. Rock stations bellowed this thing from coast to coast upon release, which allowed the band to choogle out the rest of the 1970s before synthesizers, spandex, and headbands laid waste to blues-based grandiloquence such as theirs.

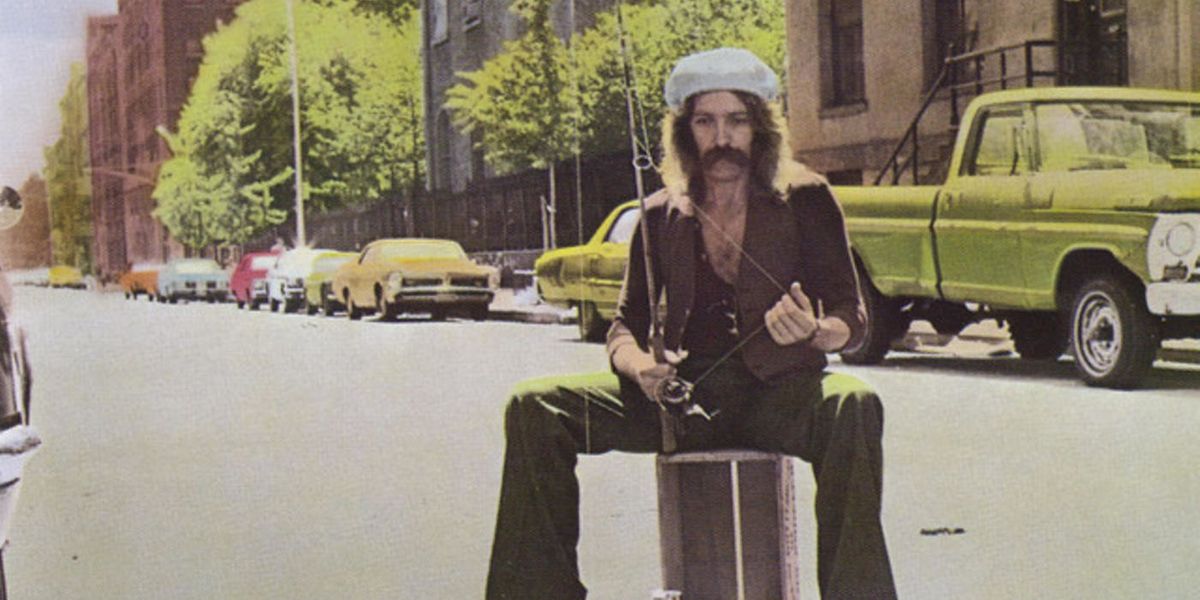

They even managed a brief mid-1990s reunion of the original line-up before Peverett and Price passed away, leaving drummer Roger Earl to own the name and play in his own Foghat cover band, not-ironically called Foghat. Perhaps it’s fitting that he’s pictured alone, fishing out of a New York City maintenance hole on Fool for the City’s front cover. Earl has also been busy turning Foghat into wine at Foghat Cellars, which makes a decent Pinot, as it turns out. It definitely impressed Stephen Colbert and guest Fred Armisen during a Late Show tasting.

It’s likely that “Slow Ride’s” essence is best summed up in Richard Linklater’s Dazed and Confused, a film depicting the debauchery of a Texas high school’s last school day before summer vacation circa 1976. At the movie’s end, Wiley Wiggins’ Mitch Kramer sneaks past his mom after a night of partying, making his way to bed just as the sun comes up. Safe under the covers, he slips on a pair of massive padded headphones and cranks Foghat’s anthem as loud as he possibly can. That final shot of him, eyes closed, is perhaps one of the most incredible cinematic interpretations of pure bliss ever filmed. Plus, Linklater managed to further immortalize “Slow Ride” in the process.

As for Foghat, while they never quite had the songs to match their hard-rock peers, they didn’t have those bands’ embarrassing posturing or excesses, either. But for a moment, Fool for the City found them putting their glitter-embossed Converse Chucks on hallowed stadium ground. Their pedestrian, blue-collar boogie hinted towards the UK’s pub rock scene as well; in fact, Dave Edmunds had a hand in the recording of their first LP. They even beat the Talking Heads to covering Al Green’s “Take Me to the River” by two years. Thanks to “Slow Ride”, Fool for the City ultimately gave them popularity, which managed to ride out punk and disco (a genuine defense).