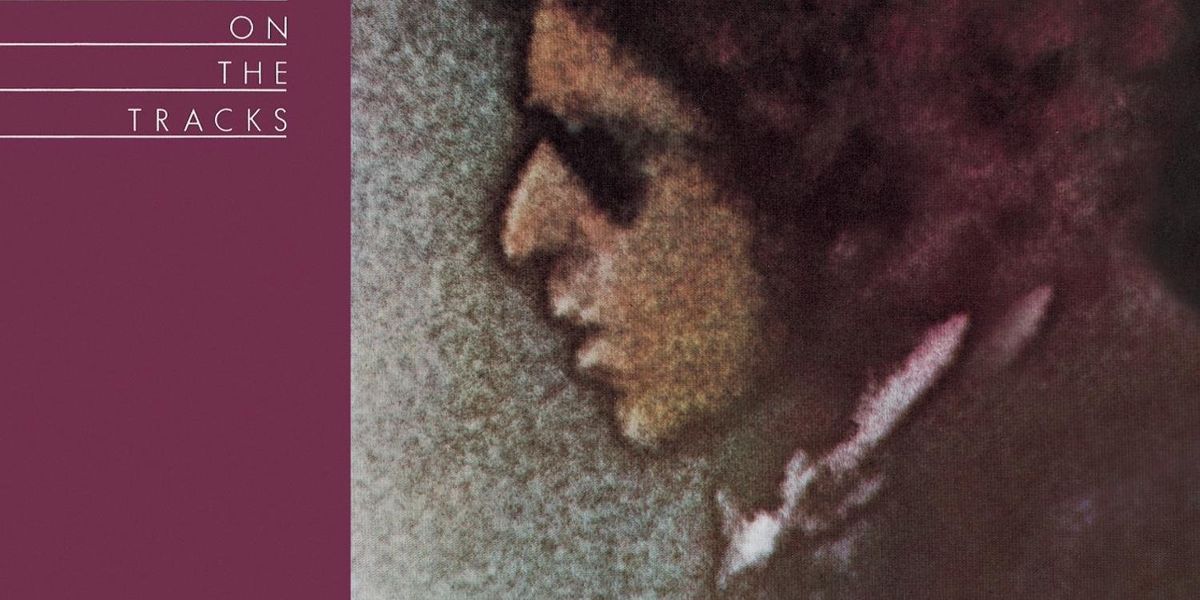

Klinger: All right, Mendelsohn, I know that in the past you’ve been somewhat, shall we say, lukewarm to our man Bob Dylan here. I’ve just about convinced myself, though, that Blood on the Tracks is the album that will change your tune. No obfuscating abstract lyrics, no fuzzy-ish arrangements, just a stunning display of heartache and loneliness, honed to a diamond-like precision by a man who reveals himself to be a true master of the form.

So I’m eager to hear what you have to say here. Is this the one? Has Bob Dylan finally won you over?

Mendelsohn: This album is very pretty. Very pretty and very sad. I imagine that Blood on the Tracks is useful fodder for any college-age troubadour lothario who enjoys preying on young, innocent, artsy girls who have yet to become jaded at life due to heartbreak at the hands of a guitar-wielding Don Juan.

All the guy has to do is play a couple of these songs while staring deeply into her eyes, and the girl will say, “Oh, somebody must have really hurt you. Here, let me make it all better”, and then he’ll say, “Someone did hurt me, but most of these songs are about the works of Anton Chekhov”, which immediately results in the girl taking off her pants.

Since I can not play the guitar and am no longer allowed on most college campuses (due to several incidents stemming from my uncontrollable mascot rage), this album, while enjoyable enough to listen to, is of no use to me.

Klinger: Well, my version of “You’re Gonna Make Me Lonesome When You Go” was popular at the Peace Coalition hootenannies back in college, but I can assure you it never led to the lurid scenarios you describe.

And frankly, I am crestfallen that you don’t see this as much more than an enjoyable album. Crestfallen and a little suspicious. Are you really unable to appreciate the cinematic scope of this album? Not just in story songs like “Lily, Rosemary and the Jack of Hearts”, but also in more seemingly straightforward tracks like “Simple Twist of Fate” and “If You See Her, Say Hello”.

Lyrically he’s delivered the atom bomb of singer-songwriter albums, and all you can say is that it’s pretty? I think you’re up to something, Mendelsohn, and I won’t rest until I figure out what it is.

Smoke by werner22brigitte (Pixabay License / Pixabay)

Smoke by werner22brigitte (Pixabay License / Pixabay)

Mendelsohn: Sorry, pal. It’s just not doing it for me. If I were starring in a big-budget rom-com with this album, the critics would ding us for lack of on-screen chemistry. There are no sparks here, despite my repeated listening—and I’ve been listening to it over and over and over all week long. But please, don’t mistake my lack of enthusiasm for lack of appreciation. I appreciate this album. But I’m beginning to think that any love affair between Dylan’s music and my ears is never meant to be.

Klinger: But what about the vitriol in “Idiot Wind”? You love vitriol! And “Idiot Wind” features my very favorite kind of vitriol—the kind that inevitably points back toward itself. The song starts with broad imprecations against the generic “they”, and then delivers a lightning-fast series of body blows toward Dylan’s favorite target, “you”. But by the time it’s all over, he’s brought it all back home to the far more poignant “we”. “We’re idiots, babe; it’s a wonder we can even feed ourselves”. It makes “Positively 4th Street” sound like a rough draft.

See, for me, that’s the beauty with so much Dylan, and Blood on the Tracks in particular (it is, for what it’s worth, my favorite Dylan album). You’ll hear these lines ricocheting around, and you know you’re not going to catch them all the first time. So you keep listening. Then in the repeated listenings, the patterns start to emerge, a little like abstract expressionist art. But then I’ve been listening to this album since about 1987.

Anyway, let’s go back a bit. What is it you can appreciate about this album?

Mendelsohn: I appreciate that it doesn’t want to make me cut off my ears. Is that good enough? No? Fine. I appreciate Dylan’s songcraft, on full display, and at its apex on Blood on the Tracks. There is a reserved simplicity to this album that is hard to find these days. Too often, artists and producers will cram as much as possible into the available space. Dylan fills out the musical space almost perfectly. The production is exquisite, each guitar flourish perfectly placed (except for the flubs in “You’re a Big Girl Now”), each bassline rolls in harmony, each blow of the harp rising out of the arrangement in time. None of it overpowers the next, they all work hand in hand to create an expansive sound despite the unplugged nature of this record. That dichotomy also applies to the overall simplicity of this album that belies the intricate orchestration making up the majority of these songs.

I also appreciate the fact that this will be the last Dylan album I’ll have to listen to for at least another year. I’m sick of hearing him wheeze like a beaten cat. I don’t care how poignant his lyrics are.

Klinger: Ah, but you will have the distinct pleasure of listening to a butt-load of artists who took their musical (and, let’s face it, vocal) cues from Bob in one form or another. Some of those folks may even have sprung from the singer-songwriter movement, whose intensely personal lyrics came to define the period that flourished right after Dylan’s mid-’60s heyday. And that got me to thinking.

Do you know who Dylan reminds me of on this album? Ty Cobb. Bear with me here.

Ty Cobb came into baseball well before the era of the home run king. It wasn’t until a young upstart named Babe Ruth started racking up the dingers that the press even started making all that big of a deal about them. Legend has it that they once asked Cobb why he didn’t hit more homers. He said baseball wasn’t a game about home runs. It was a game of strategy—hit a double so that the next guys can fill the bases, and you’ll score more runs. But, he said, if you think this game is just about home runs, I’ll show you. And in the next game, he hit four home runs in four at-bats.

Dylan’s a lot like Cobb in that respect. Bob had seriously agitated the press with Self Portrait, and they had been a bit lukewarm about him in the years following. It looked like Dylan’s day had passed in favor of the confessional singer-songwriter. Then seemingly out of nowhere, he turns up and beats them all at their own game. Critics, beneath their gruff, doughy exteriors, love a good comeback story, and Blood on the Tracks was just about the greatest since the Resurrection of Elvis in 1968.

Mendelsohn: That’s an interesting comparison. If Dylan had smashed his guitar over a couple of heads, or at the very least stabbed someone, I’d say it would be completely fitting. As it is, though, I think Cobb would be spinning in his grave if he knew you were comparing him to some guitar-playing singer-songwriter. I’d even go so far as to say that if Cobb were alive he’d probably pick up a guitar, write a song to put Dylan to shame, break the guitar over his knee, stab you in the thigh with the sharp end of the bridge, lay down a bunt with what’s left of it, go first to third on a single to right field, and then steal home.

Maybe I’m just not compartmentalizing Dylan enough. I don’t see the phases he went through. I just see DYLAN. So Blood on the Tracks may be the greatest comeback of all time, but for me, Dylan has always been there, looming. Insert cliche about trees, re: view of them here.

Klinger: Maybe you should stop thinking about Bob as the Spokesman for a Generation whose work has to be processed like Velveeta or the five stages of grief. I think you can’t see the Bob for the Dylans.

This album is also beloved among those given to romantic sad-sackery. Is it possible you haven’t loved and lost enough to ache your way through songs like “Shelter from the Storm” or “Tangled Up in Blue”?

Mendelsohn: You’ve nailed it, Klinger. I don’t like romantic sad-sackery. Regardless of the amount of loving and losing I’ve done, I have no sympathy for Dylan or his failed relationships and having to listen to him moan about it like a heartbroken teenager annoys me to no end. I had the same problem with Van Morrison’s Astral Weeks. It was a beautiful album, but having to listen to musicians wallow in self-pity fills my heart with rage. Find some rebound strange and move on. Hell, why not really stick it to the ex and write the album about the rebound strange. That’ll show them. Dump me, will you? I’ll write songs about the next person I meet, even if they give me the crabs.

I might have carried that one on a little too far.