With everything going on in today’s fraught world, it can be easy to lose sight of the big picture. Fortunately, there are scientists struggling on both ends of the human experience to keep that big picture in focus. On the one end, there are the scientists and astronauts working to clarify our position in the cosmos – putting in clear focus just what a fragile, remarkable little portion of the galaxy this pale blue dot is that we cling to. It’s with them that humanity’s future lies, and our potential for learning to live in this wondrous universe that’s almost too vast to conceptualize.

On the other end of the spectrum, archaeologists are working hard to explicate the human experience thus far. But it’s more of a struggle than it should be, especially when archaeologists must battle not just the overgrown jungles and sands of time, but also budget cuts, repressive politicians, warring states, greedy commercial developers, and looters. Two giants of the discipline – Brian Fagan and Nadia Durrani – have penned an eloquent novella-sized essay extolling the vital significance of archaeology to our present world. Bigger Than History: Why Archaeology Matters is a broad-ranging and timely reminder.

They consider, for instance, what archaeology can contribute to the study of climate change. There is, of course, the obvious. The very existence of climate change, and the chronicle of our planet’s ecological history, has been revealed – an ongoing process – thanks to archaeology. But archaeology’s contribution to the conversation goes beyond merely chronicling the planet’s past. As contemporary societies struggle to adapt to climate change, the past can offer revealing solutions.

In some parts of the world, archaeological work has revealed historical and prehistoric agricultural techniques superior to those in use today, particularly ones adapted to specific regional locales. Excavation of ancient agricultural practices in places as varied as highland Bolivia and arid, mountainous Yemen – areas that have suffered as a result of war and colonization that disrupted traditional agricultural practices – have revealed ancient cultivation techniques that can produce superior crop yields to those presently in use. (The more recent techniques were often introduced as part and parcel of modern processes of colonization.) Archaeology, then, doesn’t merely chronicle climate change — it can reveal ways of adapting to it based on historical and prehistoric precedent.

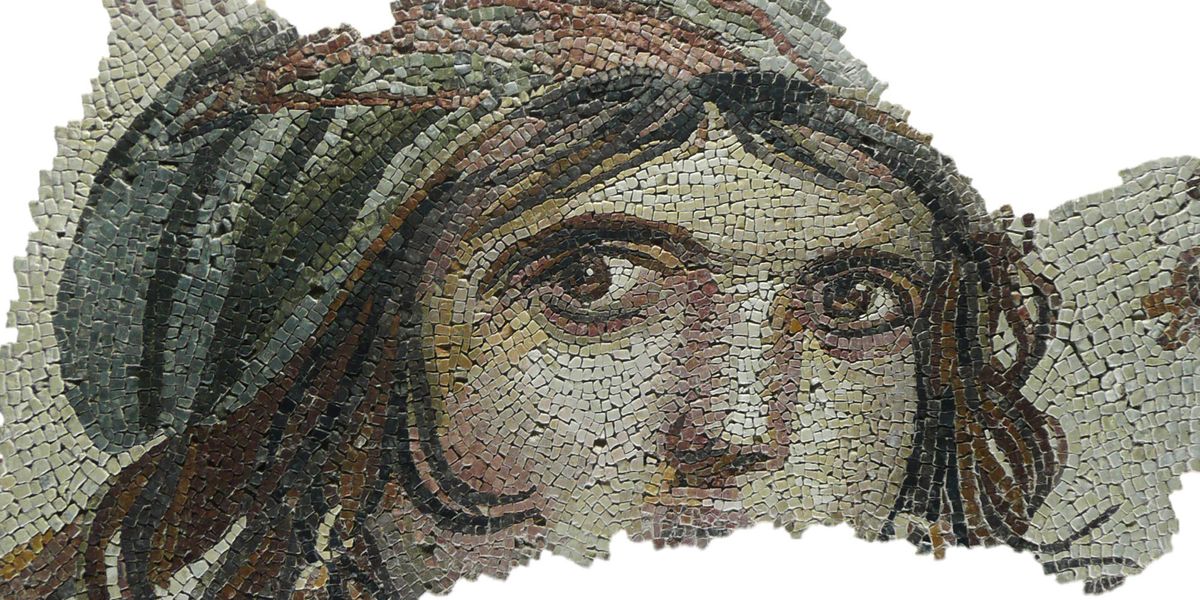

Image by ArtTower from Pixabay

Archaeology also reveals the success strategies and limits of large-scale societies faced with climate crises. Climatic reasons have been responsible (often in conjunction with other factors, sometimes precipitating or exacerbating those factors) for the collapse of many advanced societies throughout history and prehistory. Often, the solution to climate stress in the past was for people to simply walk away from over-stressed cities and towns, and return to their rural roots in small-scale villages. This pattern repeats throughout history in different parts of the world. Of course, on today’s overpopulated planet, that’s no longer an option.

More useful is the realization that societies that successfully adapted to climate change and climate crises did so by large-scale, multi-generational infrastructure and planning projects. From ancient Egypt and 16th century China to the Chimu of ancient Peru, large-scale state-directed projects – irrigation networks, grain storage systems, agricultural infrastructure – coordinated by governing regimes over broad areas, and with planning for future years and generations in mind – was key to mitigating the risks imposed by uncertain climatic events.

This should be a sobering thought for us. Unlike the climate challenges of the past – which were mostly due to natural events – today’s climate change is human-induced, and more serious than any humanity has yet faced. Yet the ongoing practices of governments — which avoid undertaking broad nationalized infrastructure projects and instead expect a consistently incapable and persistently self-centred private sector to deal with crises on a short-term basis — is directly antithetical to any strategy that has worked in human history.

What modern societies are doing, or not doing, is more akin to the ultimately unsuccessful methods of societies like the Moche. They responded to their climate crises by donning elaborate ritual paraphernalia and undertaking mass human sacrifice, praying rather than scientifically and rationally tackling the crises like their successors in the region, the Chimu. The Moche were constantly at the mercy of climatic events, which shaped their settlement patterns and wrought frequent devastation. The Chimu state, however, with its complex network of irrigation works and agricultural diversification, achieved a superior and more sustainable degree of stability.

Archaeology has a lot to say about gender, as well. While early archaeologists brought their patriarchal lens to the discipline, that has changed dramatically. More open-minded and scientifically rigorous work has revealed there’s no such thing as universal human gender roles, and that even gender identities have varied dramatically throughout history and prehistory. A considerable number of warrior burials from northern Europe, the far East, and elsewhere, which were presumed upon discovery to be men, have been reevaluated through skeletal analysis and revealed to be burials of women warriors.

Meanwhile, observation of near-historical and contemporary hunter-gatherer cultures reveals that far from the ‘man-as-hunter/woman-as-gatherer’ dichotomy that was uncritically assumed in the early 20th century, such roles are actually very fluid in practice. Even the types of grave goods found in burials, which was long used as a marker of gender, has been revealed to be more gender-fluid than hitherto thought; in some societies, age is a more direct correlate with grave goods than gender. In these and other ways, archaeology has helped to reveal that gender roles in the past were not, in fact, always as patriarchal and cliché as 19th and 20th century interpretations made them out to be.

Archaeology also has a lot to say about states and borders. Many people in today’s world consider ‘peoples’, nation-states, and borders to be natural and rooted in historical fact. And there’s no shortage of nationalists and populists – from British colonialists and the Nazis to today’s tyrants like Turkey’s Recep Tayyip Erdogan or India’s Narendra Modi – who promote biased and politically convenient interpretations of the past. But archaeology has a unique ability to disempower such claims.

Archaeology shows up the artificial nature of nation-states, borders, and peoples alike – fluid movement and intermixing of populations has been the norm for much of human existence. Nationalist and populist regimes try to exclude versions of history that don’t accord with their imagined pasts, but truly rigorous and scientific archaeology will consistently undermine their politicized claims. And while it’s true that archaeologists in the west and other parts of the world have historically been insensitive (let’s be honest: rapacious) in appropriating the cultural and human artifacts of still living cultures, the authors acknowledge this historical wrong with humility and with attentive discussion about contemporary efforts to work with living communities in excavating, preserving, and celebrating their material past.

The People Without (Written) History

A key argument the authors make is that archaeology offers access to a much greater span of time and humanity than does history, which is the study of the written past. History only encapsulates the recent 5,000 or so years of the written word, with the bulk of that written history only occurring in the last 400. Yet archaeology covers the entire seven million years since humans split off and went our separate ways from the chimpanzees. “Archaeology is never limited to the words of literate people, by geography, or time,” the authors write. Moreover, “much of history was written (and therefore embellished) by the victors and the elite.”

Archaeology, they observe, provides a more complete and objective view. Studying the material remains of illiterate villages gives voice, in a sense, to the people who lived in them, and who can share parts of their story with us despite the class or political divisions under which they lived. The authors examine, for instance, recent research on material remains of early Chinese migrant worker communities in North America, of which few written records exist yet which archaeologists have used to provide a much fuller picture of the Chinese role in building America. Archaeology can provide an essential corrective to the claims of political leaders, revealing, for instance, the survival of local cultural practices under occupation and colonization, or the reality of poverty and starvation which belie the boasts of pharaohs and modern governments alike who seek to cover up these less complimentary realities.

Image by ESD-SS from Pixabay

There’s a caveat to be made here, for there’s an important distinction between historical figures writing in their own words, and material remains interpreted by archaeologists. No matter how embellished they may be, written records reflect individuals’ interpretation and expression of their subjective realities (inflected with whatever other considerations mattered to them). Archaeological analysis, on the other hand, is always filtered through the personal and cultural lens of the archaeologist, and the history of archaeology reveals quite clearly just how partial and subjective those interpretations can be.

Indeed, archaeological work can produce interpretations as varied as the diverse ideas held by the society from which the archaeologists hail. One need look no further than the controversy generated by Kara Cooney’s recent study When Women Ruled the World for a powerful example of this. Her snapshots of female rule in ancient Egypt contain a great deal of speculation and interpretation, much of it from a gender essentialist and feminist perspective that’s generated controversy from both other feminists and sexist male scholars alike. Yet Cooney’s thoughtful analysis is hardly less intelligent than any number of other classics of archaeological speculation by male scholars, and it offers a rich and plausible interpretation of a distant and sparsely documented past. Yet her cogent and creative application of feminist (albeit gender essentialist) principles has aroused fierce emotional response in scholars and lay readers alike.

Of course, none of this should be taken as a reason to privilege historical records or oral traditions over material remains. Written histories, like oral traditions, can be objectively incorrect as well. They can be invented or embellished to serve political ends, or to cultivate particular narrative understandings of a people’s identity. This doesn’t make them wrong, any more than it makes archaeological interpretations wrong. What this conundrum underscores is that we should not give uncritical primacy to any single one of these approaches.

Human existence is messy and complicated; our very existence a combination of subjective experience, complex and conflicting interpretations of that experience, and objective reality. Archaeology offers an important – a critically important — piece of the entire puzzle. Which underscores tidily, in the end, the very point the authors seek to make: we cannot understand our past, or ourselves in the present, without archaeology.