1. “Everything in Its Right Place”

I still remember where I first listened to Kid A. There aren’t many albums I can say that about, but most of us at least remember how ridiculously anticipated the album was as the follow-up to OK Computer. Sure, that sense of anticipation is at least part of why I vividly remember putting the disc on in my car stereo as I left the parking lot of Port Huron, Michigan’s only mall. No, the reason the memory is so vivid is nearly entirely because of “Everything in Its Right Place”. The song opens the album with warm electric piano chords, and subtle bass, glitchy vocal sound effects, and a soft kick drum beat before Thom Yorke’s falsetto slides in on top of the mix. I fell in love with it instantly.

Kid A was an album that featured all sorts of rumors in the hype leading up to its release. But it hit before the internet really became a force in the music world (no leaks, unlike the follow-up Amnesiac). And with the band doing no promotion, including no lead single, nobody knew quite what to expect. We knew Radiohead was going in a more electronic direction, and that it would probably be challenging and weird. Kid A proved to be both of those things, but by putting “Everything in its Right Place” first on the disc, the band let us know that they hadn’t abandoned melody and songwriting in their quest to expand their musical horizons.

Still, the song effectively teases what is to come on the rest of the album. Those glitchy vocal effects pop in, under, and between the rest of the track’s music. There is a lot of atmospheric, electronically manipulated strangeness zipping around the margins of “Everything in Its Right Place”, and it finally begins to engulf Yorke’s lead vocal as the song fades out in its final 40 seconds. It’s key that the disintegration doesn’t happen until the end, though, because what you remember about the song is its melodic elements.

Kid A has developed the reputation of being a cold, dispassionate album, but the opening track is full of warmth and emotion. Yorke sounds stressed-out, singing about “sucking a lemon” and not quite hearing “what was that you tried to say”, but placed in the context of the song’s low-key musical bedrock, he feels a lot less stressed than he sounds. The album’s first song elements come together perfectly, both as a composition and as a table-setter for the rest of the disc. “Everything in its Right Place” lives up to its name. — Chris Conaton

2. “Kid A”

While many hail Kid A as an out-and-out masterpiece, there are still some people that just never jumped onto that same bandwagon, calling the album dark, alienating, and sometimes even too “out there”. It’s argued that there is no beating heart at the center of this digital beast, but, to those people, I simply offer up the title track: the calmest, catchiest, and warmest song to be found here, like a cabin on the top of a snow-covered hill at night with a fireplace roaring inside — that just so happens to be occupied by a robot who slurs his words way too much.

With its bumpy little backbeat, pseudo music box twinkles, and warm synth pads, “Kid A” is almost embryonic in tone, creating a comfortable little aural nest for Thom Yorke’s damaged, distorted voice to rest in. Upon first listen, it’s nearly impossible to discern what the hell he’s saying, although fragments come through: “I slipped on a little white lie” is telling, as is the biting puzzler “we got heads on sticks / and you’ve got ventriloquists”. In interviews, Yorke has said that he hid his voice in this song specifically because some of the lyrics were too “brutal and horrible” to sing as is. The distortion made it easier for him to attain a sort of psychic distance from the material. It could also be argued that if this really is the first waking moments of that proverbial human clone, then he’s already got some rather pointed things to say, as if the product of absolute artificiality can somehow instantly see through our own artifices and facades, without even trying. Perhaps he will lead the rats and children out of our homes after all.

However, what “Kid A” does in the grand scheme of things is of far greater importance. Immediately following the numerous looped voice samples that help close out “Everything in Its Right Place”, the song “Kid A” takes us one step further by establishing the voice as an instrument, not a mere conveyor of words and emotions. The band was already “bored” of guitars at this point, and Yorke — being Yorke — loved the idea of having his voice be decentralized to a certain extent. Suddenly having his vocals be electronically mangled didn’t just seem like a cool idea anymore: it seemed like the only option. Then, placing such a unique song as the second track of the album effectively disarmed listeners from all expectations that they had going forward. After hearing both “Everything” and “Kid A”, suddenly the rest of the disc — its out-and-out techno beats, its avant-garde jazz horns, it’s the faux-Disney conclusion — seemed to be a bit more within aesthetic reach. Once all your expectations are shattered, suddenly, the alien becomes a bit more familiar and all the more pleasing in the long run.

Yet “Kid A’s” most remarkable aspect is its simplest: the fact that it lifts. Once the voice and bass drop out at 2:53, we are left with mere digital squiggles and the quiet thumping of drums (about to break out into “Sing, Sing, Sing, Pt. 1 & 2” at any second), which soon get lifted by soaring synth wings to achieve something that borders on hopeful, joyous even. It’s a rare moment of out-and-out musical optimism for the band, and it contains an energy that doesn’t appear anywhere else on the disc. It’s a unique, powerful moment that conquers us with its unassuming beauty. “Watch it,” the distorted voice tells us at the end of the track, not realizing that such a demand is futile, for we’ve been watching the whole time, our jaws agape in amazement. — Evan Sawdey

3. “The National Anthem”

Radiohead fans accustomed to the infamous “Creep”-y styles of the ’90s really had their patience tested with the first two tracks of 2000’s Kid A. So far, guitars and bass appeared to be absent, and the percussion felt synthetic at best. No one can be blamed for thinking that Radiohead was stubbornly refusing to sound like a “real band”. But for anyone who persevered through the disembodied alien mutterings of Thom Yorke matched to vintage keyboards, “The National Anthem” felt like a relief. At least it did at first.

“Everything in It Right Place” is compositionally simple but wins out with a sneaky headphone mix. The album’s namesake is more carefully charted, though the main music-box-gone-celestial riff didn’t make it any more accessible. But from the start of track three, that all goes out the window. At last, a bass guitar! Playing a fairly straightforward riff at that! (apparently, the three-note motif in question was composed by a 16-year-old Yorke) And as Phil Selway kicks in with a not-too syncopated drum beat, devotees of The Bends everywhere exhaled a collective “aaaaahhh…” Even if this newfound cyclical groove had more in common with Massive Attack than anything from Radiohead’s past, the listener nevertheless felt like they were out of the woods and into the rock.

The use of the adjective “rocky” would prove more apt.

“The National Anthem” thrusts a different Radiohead influence down one’s ear canal: Charles Mingus. Sure, Kid A is heavy on electronics, samples, and distorted vocals, but that doesn’t mean that there’s no room at the inn for some noisy avant-garde jazz. The compositional style of the great Underdog would shine through Radiohead’s music in other ways. Compare the shifting downbeat of “Pyramid Song” from Amnesiac against “Freedom” from The Complete Town Hall Concert for further proof). “The National Anthem” was a chance for Jonny Greenwood to show us that he can corral a small ensemble of wind instruments into sounding like, as one critic put it, “a brass band marching into a brick wall”.

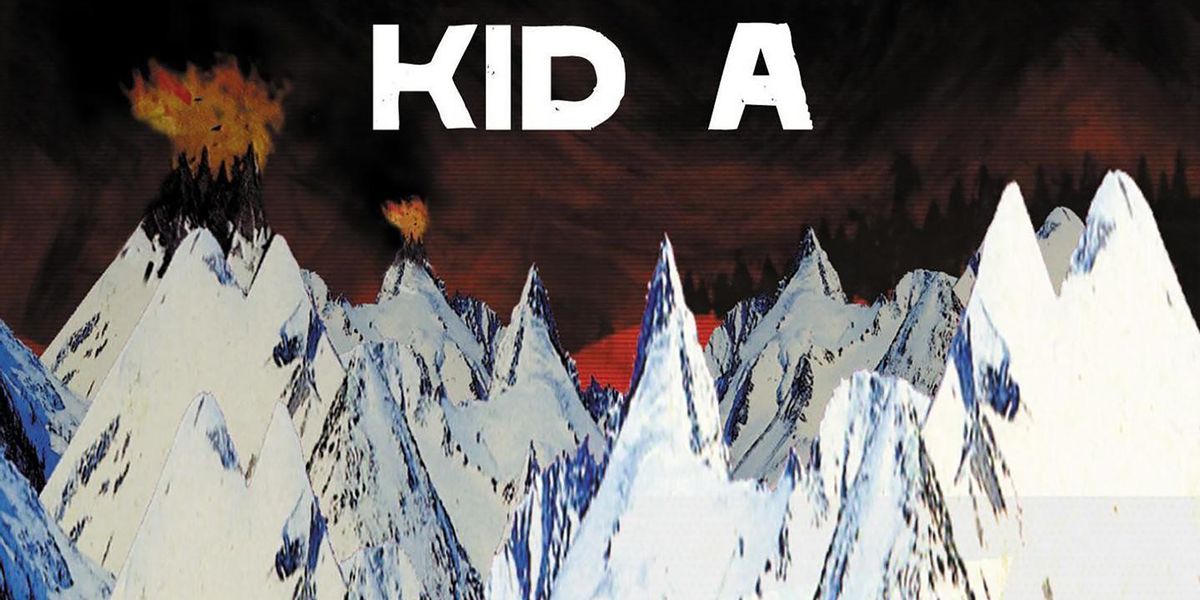

The song’s lyrics are cryptic, which is typical of Radiohead. Not only can fans on the internet zero in on one true meaning, but some people hear them differently: is the repeated refrain “It’s holding on” or is it “what’s going on?” The sleeve for Kid A offers no lyrics, just wacky landscapes. What’s clear is Thom Yorke paying a visit to his old friend paranoia: “Everyone is so near / Everyone has got the fear.” Being neither nationalistic nor anthemic, everyone was going to have to sort this one out later.

It’s a little past the three-minute mark where Yorke and Greenwood achieved their desired “car-jam” sound. One trumpet, two alto saxophones, two tenor saxophones, one baritone saxophone, one trombone, and one bass trombone all improvise simultaneously. Had one or two of these instruments been showcased at a time, the whole thing would be an easier pill to swallow. But why do that when you can get so much closer to “Better Git It In Your Soul” by having everyone solo at once? While conducting, Yorke and Greenwood instructed their players to “just blow.” This might be different from how the giant, imposing bandleader would have handled it back in the day (barking orders, threatening physical harm). Still, Radiohead’s outcome is no less of a racket than anything you’d hear on Mingus Ah Um.

The three-note bass riff has been going this whole time with drums dropping in and out intermittently. By around 5:12, the horns have the rug pulled out from under them completely as they continue their solos with no corresponding theme in sight. A quarter rest is given, and suddenly all eight horn players give one last blaring note before exiting. One can almost picture Gunther Schuller leaning over his conductor’s stand, hand outstretched and shaking, hair flailing, begging his big band to burn a hole in the back of the concert hall. Had Mingus not been cremated in 1979, he’d probably be giving a thumbs up in his grave.

Thus concludes what is debatably the most challenging five minutes and 50 seconds of what is debatably Radiohead’s most challenging album. Even though “The National Anthem” is one of the few songs on Kid A to thrive mostly on organic instruments, this is the song that most listeners probably chose to skip over in future listens, if they even felt like revisiting Kid A at all. We can’t tell if the paradox was intentional or not, but Radiohead were already aware of the power behind the song. It had been a holdover from previous album sessions, and bassist Colin Greenwood was cited as saying that it was too good to be restricted to being a B-side.

And you don’t pick just any old song to open your live shows, now do you? — John Garratt

4. “How to Disappear Completely”

Brace yourself for conceptual whiplash, people younger than me: in 1999, I was so obsessed with my fan site-assembled mishmash of Radiohead B-sides, overseas bonus tracks, early material, and live recordings that I temporarily installed an extra hard drive so that I could pass a friend those songs in OGG format (because MP3 wasn’t always the default file choice) for him to burn me an audio CD at his dad’s computer store, the first burned CD I’d ever seen. This was all because I couldn’t stand the thought of not playing those songs on my Discman. I mention the logistics of hearing “How to Disappear Completely” for the first time because, as much as everyone talks about Kid A as some sui generis Dawn of a New Era, the album was rooted in a bizarre, transitional era for music fans.

I wish I still had that CD; I’ve never tracked down the embryonic, live “How to Disappear Completely” that ended it. You can find many gorgeous live renditions on YouTube, but I’m pretty sure that the version I had lacked the swooning, oceanic depths of the recorded version and subsequent live performances (a sound the band has revisited on “Pyramid Song” and “Sail to the Moon,” but never with quite the same blackly feverish intensity). Instead, the version I had was mostly acoustic guitar; hearing the synthetic whalesong of the album version reverberate through the frame of the car I was in at the time, driving down a country road in the dark, was a moment of startling revelation. There may have been leaks, but I was unaware of them. These days, when friends deliberately avoid listening to a keenly anticipated release until they can buy the physical album, I always think back to that first listen in the car.

But the thing about the ghostly, keening beauty of “How to Disappear Completely”, a beauty that was born out of Thom Yorke’s inability to process the huge crowds Radiohead was playing in front of, a beauty diametrically opposed to the “strobe lights and blown speakers” the narrator needs to escape from, is that such a desperate and claustrophobic song is actually uplifting. “That there / That’s not me” isn’t exactly the most optimistic beginning. Certainly, there’s an edge of anguish to the repeated calls of “I’m not here / This isn’t happening”. But “How to Disappear Completely” is a song caught at the precise midpoint between panic and exultation, between vertigo and flight. It’s a song that recognizes and appreciates the terrifying joy and ghastly freedom of leaving everything behind. If you’re a bad place, “I’m not here” can be reassuring, even defiant; in other circumstances, the song can play out as anything from melancholy to nightmarish.

Near the end, after singing the last actual lyrics, Thom Yorke continues to wail wordlessly as the string arrangement twists into a warped, yawning abyss around and under his voice. It feels like the song is closing in on you like some terminal point is being reached. It sounds as if the song must end this way, by swallowing the singer. And then, as Yorke continues without pause or quaver, the strings recede sharply, then surge in again, restored to their original brightness, the vocals turned into a clarion call where moments before they’d been a drowning man. “How to Disappear Completely” works equally well in either mode; more importantly, it inhabits both simultaneously. — Ian Mathers

5. “Treefingers”

Much in the fashion of David Bowie’s work with Brian Eno on 1977’s Low (“Warszawa”, “Subterraneans”), Radiohead’s “Treefingers” is a culmination of Kid A‘s angst put softly into water, bathed and echoed, and made sublime. “Treefingers” is an ambient piece that sings unlike its counterparts on the album. Ed O’Brien wrote it first as a guitar solo then processed, no doubt, through some vast Eventide processor or Pro-Tools plug-in before emerging as its strange, liquid self.

The track is likely born out of Radiohead’s then-evident interest in Warp Records, the 1990s birth of IDM, and artists like Squarepusher, Aphex Twin, and Autechre. “Treefingers” most resembles Aphex Twin’s work on Selected Ambient Works Volume II, a massive double-vinyl collection of spare and mostly beatless synthesized compositions, some carried by synth washes or simple wind chimes clattered somewhere in Twin’s native Cornwall. This album sometimes called SAW2, bristles the new age trappings of most of its ambient-leaning ilk and plays much like a tuneful Lustmord caught easing out of his dark ambient safe-zone. There is no direct correlation between SAW2‘s tracks and “Treefingers”, but I should hope that Greenwood et al. found it at the least to have been of commensurate influence when processing O’Brien’s guitar noodling.

SAW 2 is built with contributions of synaesthesia, or “the production of a sense impression relating to one sense or part of the body by stimulation of another sense or part of the body”. That’s a suitable way to perceive “Treefingers” and, for that matter, many of Radiohead’s other ambient attempts. This, barring its heavy low-frequency filtering, surely is part of the reason that “Treefingers” is so oft described as sounding like it was recorded underwater. The song’s simple structure, aleatoric-seeming chordal mood, and blossoming progression could be the attributions of an artist interpreting the soft sound as images of stars seen from beneath a waterline, moving shapes across the sky, planes at night, the way water reflects the moon, ripples on a pond surface, bright and falling lights, and rain on lone city streets. “Treefingers” is cast outside of Kid A‘s jazz-laden, percussive stature, and it exists somewhere in the not-so-barren outland. — Jason Cook

6. “Optimistic”

“Optimistic” is murky and propulsive and knotty, but it’s quite easily the closest that we get to a conventional rock song here. Being the only predominantly guitar-based song on Kid A, with only the fuzzed-out bass grunt of “The National Anthem” coming anywhere close to a reasonable claim on that distinction elsewhere, is enough to distinguish it. But “Optimistic” is still a far cry from such earlier anthems as “Just” or “Sulk” or even a deranged fit like “Electioneering”.

The rhythmic, cycling, Crazy Horse-like groove that “Optimistic” locks into isn’t the kind that elicits the cathartic, fists-in-the-air transcendence but rather pensive twitching and evasive ground-staring. Suppose rock and roll is, even (or perhaps especially) at it’s most anguished and enraged. In that case, an extroverted and communal art form, Radiohead do their best here to render it the soundtrack to that favored topic of theirs, isolation.

Then there are the words, which, in keeping with the song’s grudging accessibility, are surprisingly coherent in contrast to what Thom Yorke was dishing out at the time. A reference to “living on an animal farm” is particularly illustrative; where Yorke draws clear influence from George Orwell throughout the band’s discography, this reference is still atypically explicit. Likewise, even the most literal-minded of listeners is unlikely to miss the scornful sarcasm of “If you try the best you can / the best you can is good enough”, particularly when it comes draped in Yorke’s disaffected sneer. It is a statement that now feels, from a backward-glancing perspective on the latter half of 2000, like a harbinger for things soon to come: a stolen presidential election months later, a decade of widespread disapproval failing to halt an unpopular war, a media culture that, apparently more “democratic” than ever in its construction, continues to highlight the very worst of us. “Vultures circling the dead, picking up every last crumb.”

Sonically and thematically, “Optimistic” is a troubling oasis in the middle of a difficult record, a seeming lifeline that quickly reveals itself as an ill omen. Still, the greatest irony inherent in a song as ironically titled as “Optimistic” may be just how backhandedly optimistic it is, offering a brief, though hardly encouraging, a moment of clarity amid chaos. If there is truth to be found amidst the distorted cacophony that defines being alive and aware in the 21st century, here it is in a quick, potent dose, to be absorbed before we are deposited — here via the half-minute of chill-house patter that ushers the song out –back into a land of confusion. — Jer Fairall

7. “In Limbo”

Like plenty of others, I had heard Kid A before it was released, having pieced parts of the album together with online leaks. Of course, I dutifully listened to my copy of the Kid A after it came out. I liked that I already felt familiar with the album.

Then I watched Radiohead perform “Idioteque” on Saturday Night Live. If you stayed in that night, maybe you saw what I saw. Thom Yorke’s body jerked wildly on stage, his eyes rolled back in his head. Jonny Greenwood was on his knees playing with wires on an analog sequencer, leaving viewers to guess which sounds he was creating. The performance matched the intensity of the song’s lyrics. Kid A now intrigued me with its unfamiliarity.

When you’re lost, you need a reference point to help you find your way. “Idioteque” was my sonic touchstone. And so it was that at the start of my Kid A experience, I viewed “In Limbo”, the album’s seventh track, as a mere prelude to “Idioteque”, the song that followed.

“In Limbo” seemed to just know its place on the album. The song thrived as an interlude, or as being liminal: it was a mostly shapeless track in the narrow space between the stately call-to-arms of “Optimistic” and the frightening beat of “Idioteque”. They certainly make for a compelling troika on Kid A, with the songs distinctly revealing the band’s various musical influences. “Optimistic” nods to the guitar-driven era of The Bends. “In Limbo” evokes a jazz session (the steady hi-hat, the improvisational guitar arpeggios). “Idioteque” showers on the electronica.

Yorke and his girlfriend, Rachel Owen, were said to be Dante devotees during the production of Kid A, so the religious connotations make sense. “In Limbo” is in Limbo, in purgatory and on the edge of Hell. If “Idioteque”, then, is Kid A‘s climactic Sturm und Drang, then “In Limbo” chronicles the coming apocalypse. Yorke reflects on feeling lost for the first two minutes of the song while the guitar meanders alongside some digital blips. Then it all merges into perhaps the most terrifying minute on Kid A, with Yorke’s wailing eventually drowned out by his own ghoulishly distorted voice. Then listen closely, or otherwise, you’ll miss what sounds like waves crashing onshore. On an album obsessed with electronic noises, the sound of water is as poignant a moment as you’ll find on the album.

It’s telling that “in Limbo” is the only song on Kid A that makes explicit reference to actual identifiable places. Yorke mumbles at the start: “Lundy, Fastnet, Irish Sea / I’ve got a message I can’t read.” BBC listeners will recognize that first line as a reference to the station’s Shipping Forecast, which gives weather conditions for each of the “sea areas” in the British Isles. Yorke’s BBC reporter can’t relay the weather forecast, but that doesn’t mean that Yorke’s storyteller (the one we can make out clearly) is lost, or at least in the sense that you don’t know where you are. This second person — maybe Owen, maybe Yorke — knows exactly where he is. The issue is that a sailor without a forecast is someone without knowledge of which sea areas — which places — to avoid. This person is horribly stuck.

When a third voice comes in at the end of the song and screams for the stranded seafarer to “come back!” a terrifying passage turns sad. The song’s message emerges: the worst way to be lost is to isolate yourself someplace, to settle in, and to lose your impulse to move on. The greatest fear is that we’ll lose our connections to others. It’s a fear as lucid as the sound of waves crashing onshore. “In Limbo” is about settling in alone and being worse off for it. Because just around the corner, on the next track, “Ice Age Comin'”. — Freeden Oeur

8. “Idioteque”

“Idioteque” is the closest thing Kid A has to a hit single. The band still plays the song at virtually every live performance; the early “blip” ads for the album featured the track prominently, and Radiohead even brought a showstopping version of it to a rare television appearance on Saturday Night Live. If Thom Yorke chose to open Kid A with “Everything in Its Right Place” because he felt that song best captured the new sound of Radiohead in the 21st century, “Idioteque” displays that sound at its most emotionally wrenching and dramatically realized. To describe the track in these terms — those of a hit pop song — is at once completely appropriate and entirely profane.

After all, “Idioteque” does its job as a pop song, with Yorke’s ethereal chorus (“here I’m alive / everything all the time”) offering one of Kid A‘s most immediate and delectable hooks. That driving beat, the clear product of the band’s attention to the Warp Records catalog, sinks its digital claws into the hips and gets them moving. You react to the song’s physicality just as quickly as its infectious melody. In other words, “Idioteque”, like any successful bit of pop music, grabs you instantaneously and viscerally.

Of course, nothing produced by Radiohead since The Bends stops there. “Idioteque” proves to be so much more than Kid A‘s finest moment of pure pop songcraft. It’s been said many times before, but play this song back to back with “Creep” or “High and Dry” or even “Karma Police” and try to pinpoint the trajectory of the band’s creative evolution into the stratosphere while hearing them maintain and hone their pop sensibilities. That forward momentum, peaking here at track eight on Kid A, defies any comparison in contemporary music. Crucially, “Idioteque” shows its compositional and intellectual accomplishments right alongside its pop strengths. You don’t need to strip away the melodic sheen to get to the heart of the song. And why would you want to? They function together perfectly.

Like most things, Radiohead, fans, and critics have already intently documented the compositional process of writing “Idioteque”. Jonny Greenwood found inspiration in a sample of electronica pioneer Paul Lanksy’s “Mild und Leise”, leading him and Yorke to construct the song around that sample’s chord progression. The band members often spoke of feeling disoriented during Kid A‘s recording, having to switch instruments, or not play anything at all. “Idioteque” shows those creative risks crystallizing into something staggeringly effective. The syncopated, polyrhythmic beat that anchors the song is sterile in its relentless efficiency, but Phil Selway’s live percussion had to be sacrificed to achieve that sensation. Indeed, the programmed drumming’s dryness proves a flawless counterpoint to the somehow warm, organic tones of Greenwood’s synths. These elements combine to create a remarkably lush electronic soundscape, every note of which becomes percussive to varying degrees of violence. The texture is alien, and we are drawn to it due to its subtle unfamiliarity.

Yorke, too, pushes himself to new heights. His patchwork lyrical method shows itself in full display here, the pulled-from-a-hat phrases strung together into a teeth-clenching barrage of dystopian images. “Who’s in a bunker?” he asks at the song’s opening, and balances this tried-and-true symbol of modern paranoia with later references to “mobiles quirking / mobiles chirping”. He’s building an imagistic portrayal of a society besieged by the sterility of technology, and he’s doing it above the backdrop of his band’s embrace of those very inorganic and digitally-minded methods. If it’s a post-modern comment, it’s one still imbued with potent emotion. His vocal performance shows his powerful register, and the recording lets us hear the very human flaws and strains in his voice. He’s floating in the atmosphere of “Idioteque’s” desperate digital wasteland, and we cling to his sense of humanity just as we feel pulled downward toward the song’s seething, smoldering core. — Corey Beasley

9. “Morning Bell”

One of Kid A‘s blips — the short spots used to promote the album back in 2000 — features a black and white animation; leafless trees spread out haphazardly across a snow-covered field with a dark foreboding sky in the background. In the less than 20-second clip, a giant stick figure with arms that swoop down towards its feet traverses across the land while a piece of “Morning Bell” plays in the background. Like many of Kid A‘s previous songs, “Bell” starts off light, slowly building itself piece-by-piece until it turns into a cacophony of cymbals and various sound effects. The portion used in this clip is, fittingly, from the latter part of the track. The loud, dissonant noise mixed with the sketch-animation makes the spot haunting and a bit mysterious — not unlike “Morning Bell” in its entirety and, to a larger extent, Kid A itself.

Looking at it from the perspective of someone who had never listened to the full track, it wouldn’t have been too much of a stretch to assume that Kid A was going to be one giant avant-garde noise experiment (and, to a certain extent, that’s what it ended up being). But once you heard the complete song, you began to understand how the fragment itself fits into the overarching narrative of “Morning Bell”.

Beginning with a scratching noise leftover from one of Kid A‘s highlights, the upbeat “Idioteque”, “Morning Bell”, settles things down a bit with a steady 5/4 drum beat, a bass line, and a smooth set of organ chords. Even with the addition of Thom Yorke’s lightly distorted voice, Radiohead keeps this path mostly clear until the last minute of the track when all hell breaks loose. A screeching guitar and other sound effects fade in, layering over one another as Yorke’s voice slowly drowns in the madness.

Unlike the majority of tracks on Kid A, the lyrical content of “Bell” follows some sort of story arc. Yorke has admitted to throwing words into a hat and picking them to write the lyrics for songs on this album, and that is apparent here with the random, poetic phrases in each verse: “You can keep the furniture / A bump on the head / Howling down the chimney.” But the song as a whole seems to allude, rather obviously, to the painful breakup of a couple. The idea of “keeping the furniture” and “cutting the kids in half” (as mentioned later on) can be interpreted as arguing about what to do with your shared possessions and your keepsakes once you split up.

But what really helps personalize “Morning Bell” is the constant repetition of the words “release me”. Whether or not you have ever experienced a painful breakup, Yorke’s falsetto seems to connect the song’s soul with its listener, as “Bell” goes deeper into a state of complete disorder. The chaotic nature goes hand in hand with Yorke’s barely audible last verse: “the lights are on, but nobody’s home/and everyone wants to be your friend / and nobody wants to be afraid … until you’re walking, walking, walking”. It represents a feeling of loneliness and abandonment.

The fact that we can pinpoint an actual message in any Kid A song is pretty remarkable, which is one of the reasons “Morning Bell” is so special. — Alex Suskind

10. “Motion Picture Soundtrack”

At the risk of understatement, Kid A is a massively depressing listen. Artistically a triumph, it’s born of difficult times: a band undergoing a difficult paradigm shift, a lead singer battling depression, and a feeling that a bunch of post-grunge lads were never supposed to get this far, not to mention, where to go next.

“Motion Picture Soundtrack” is the closer to Kid A, but its conception dates back to predecessor OK Computer, from which it was cut. Lyrically, it’s a fitting epitaph to the isolating struggles of Kid A. Unlike its sister tracks, however, “Motion Picture Soundtrack” feels almost optimistic. Sure, Thom Yorke is still the same sad fellow he’s been the whole time: “Cheap sex / And sad films / Help me get where I belong.” It also gets thrown for a loop with the final line, however: “I will see you / in the next life.” Influenced by the eerily pristine harp swells surrounding it, this lyric comes off neither particularly sad nor happy, but hopeful. It’s more than a little reminiscent of another album closer, “See You in the Next One (Have a Good Time),” from The Verve’s A Storm in Heaven. Like Richard Ashcroft, Yorke doesn’t sound judgmental, even in delivering a bitter dismissal like “stop sending letters / letters always get burned.” Rather, he seems resigned to his fate, but willing to consider the possibility of rebirth.

Maybe this goes deeper (this statement also applies to the entirety of Kid A). Yorke has said that “Kid A” might refer to the first human clone, putting a different spin on the superficially mundane depression at focus during the first half of “Soundtrack”. Like Truman exiting the dome that has enclosed his life at the end of The Truman Show, the narrator here is suffering alienation greater than the average romantic longing, and, realizing his unique position in the world, chooses to move on as a neutral observer of what’s to come.

Musically, there’s a kind of magical quality to “Motion Picture Soundtrack”, and not by accident — Jonny Greenwood acknowledged his intent to replicate the faded sparkle of a classic Disney movie soundtrack with processed harps and vocalizations. After a rather stark first part, with Yorke accompanied by a creaky pump organ, the surreally maudlin harp trills frame things like a classic Hollywood dissolve.

Maybe this is all just overanalysis. After all, the tranquil Technicolor fadeout at the close of “Soundtrack” isn’t the last thing we hear from Radiohead. Of course, there’s a hidden track, and it’s unsurprisingly abstract and electronic. Perhaps the most satisfying thing about “Motion Picture Soundtrack” is that, despite the title, it doesn’t feel all that epic. There’s no sense that anyone is trying to prove anything musically or philosophically here. It’s another way to see Kid A, as an excellent album, and one that ends not by exploding from its frustrations, but by going to bed. — David Abravanel