1. “Smells Like Teen Spirit”

It’s conventional music industry practice for record labels trying to break an up-and-coming band to release what’s termed a “base-building” cut as the first single from an album. The idea is that this lead single — specifically chosen because it contains the core recognizable elements of an artist’s sound — will get diehard fans excited enough to send it up the charts devoted to that artist’s designated format. A more melodic single with broader appeal will be issued next, with the intention that it will build upon the momentum established by the base-builder to quite possibly (fingers crossed) cross over to other formats and become a genuine sensation with consumers.

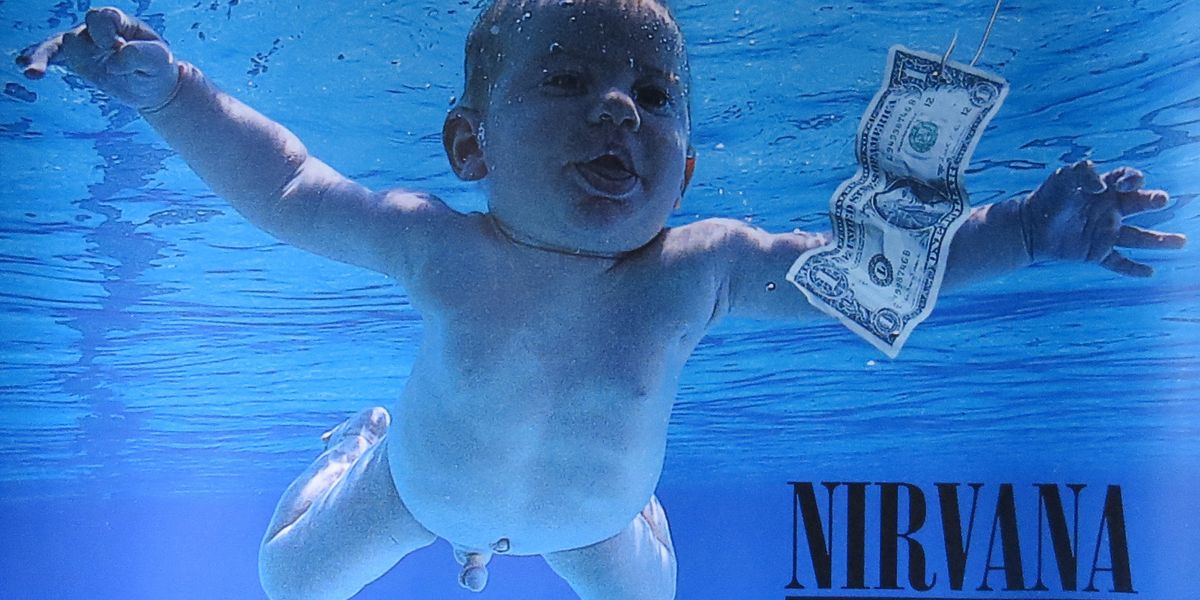

This is the tactic DGC Records had in mind when it selected “Smells Like Teen Spirit” as the initial a-side from Nirvana’s major label debut Nevermind, both of which it unveiled to the public in September 1991. “Come as You Are” was already slotted as the follow-up, as it was pegged as the potential modern rock radio hit, quite likely because its warbly guitar tone and more restrained, moody atmosphere made it more palatable to the format’s Cure/Depeche Mode-dominated post-punk leanings at the time than “Teen Spirit’s” aggressive, in-your-face alterna-rockism. Some at parent company Geffen held hopes that the possible breakout track (if it did emerge) would be “Lithium”, the eventual third single from the LP. This was the best-case scenario that Geffen/DGC could envision for its promotional plan, given the market for alt-rock at the time.

But history didn’t work out that way. What instead happened was that “Smells Like Teen Spirit” became a wholly unexpected phenomenon, the magnitude and rapid diffusion of which bulldozed DGC’s little marketing strategy so utterly that the label had to throw up its hands and (in its words) simply get out of the way. Conquering sales charts, music television, and all rock radio formats over the course of late 1991 and early 1992, the song not only became a ubiquitous epoch-defining commercial hit — peaking at number six on the Billboard Hot 100 in the United States and attaining similar heights worldwide — but it also quickly ensconced itself into the canon of modern popular music. Today, it sits in that rarified echelon of all-time greats as the one song from the last 20 years that even baby boomers in thrall of the 1960s’ overbearing cultural legacy can’t dispute is an “important” record.

Photo by Егор Камелев on U

Photo by Егор Камелев on U

What is it that’s so enrapturing about this particular song? The appeal of “Smells Like Teen Spirit” — and by extension, Nevermind as a whole — is primal and visceral, rooted in gut impulses triggered by the song’s attack. From the moment Kurt Cobain’s scratchy four-chord guitar intro is interrupted by Dave Grohl’s bone-thuddingly massive drum fills and the switching-on of a distortion pedal, it’s clear that “Teen Spirit” is a tremendous song. Driven by a lurching, thrashing rhythm and well-placed dynamic shifts to amp up or dial down the intensity as needed, the whole thing practically compels listeners to mosh along.

The tune’s chord progression is so catchy that the band built “Teen Spirit” around it, relying on Pixies-inspired contrasting loud choruses and subdued verses (where the distorted parts drop off so Cobain can play a hanging two-note lick) to move the song forward. One killer bit that is not often discussed by critics is the transitional riff that connects the choruses back to the second verse and the guitar solo, where Cobain’s gnarled, chromatic chord changes are interrupted by well-placed exclamations of the word “Yay”, which are themselves augmented by a string bend that matches the note he’s singing.

“Teen Spirit”‘s melody exhibits a simple, nursery-rhyme quality that makes it compulsively singable; it’s unsurprising then that Cobain also utilized it for the track’s guitar solo. Even though his straightforward replication of it for his lead break would forever earn him critical marks from more technically proficient players, that decision ensured that no one would ever forget it. According to Grohl, Cobain’s songwriting mantra was that music came first, lyrics second. Thus, subordinate to the main melody and Cobain’s nuanced vocal delivery, the song’s subject matter — where the lyricist ruminates on his generation, while both advocating and dismissing the concept of a teen revolution — is pretty irrelevant.

On paper the words for “Teen Spirit” might come off as patent nonsense at points (“A mulatto / An albino / A mosquito / My libido / Yeah!”), but one really shouldn’t be following the song with a lyric sheet in hand — Nevermind notably did not include full lyrics in its liner notes anyway, merely snippets of lines. And that’s how you perceive Cobain’s words on the tune, as verbal snatches slip out from his mumbled, hoarse singing to create impulsive sensations in the listener’s mind (“Load up on guns and bring your friends”; “Hello, how low?”; “With the lights out / It’s less dangerous / Here we are now / Entertain us.”; “Oh well, whatever, never mind”; “A denial”). It’s Cobain’s attitude — alternately antsy, aggravated, and snarky — that imbues his words their power. As Nevermind producer Butch Vig once said about the track, “I don’t know exactly what ‘Teen Spirit’ means, but you know it means something, and it’s as intense as hell.”

Listening to the track now, its appeal is almost mundanely obvious — it’s no wonder legions of alt-rockers spent years trying to rip it off. Indeed, those involved with making “Teen Spirit” knew it was a great song, even if they could never have anticipated how huge it would become. Vig recalled being impressed when he first heard a grainy cassette demo of the song, and, when Nirvana first rehearsed it live for him, he was so wowed that he asked the trio to play it again and again. Yet “Teen Spirit”‘s massive success was by no means ordained, and there was indeed a time when it wasn’t the reliable radio standard that it always seems to have been.

As detailed in Jim Berkenstadt and Charles Cross’s Nevermind book from the now-defunct Classic Rock Albums series, commercial radio programmers were in fact gun-shy about playing the track when it first hit the airwaves, restricting it to nighttime play due to its abrasive nature. However, market research showed that “Teen Spirit” was appealing enormously to all sorts of listeners regardless of age and gender, even when they were only played a 15-second snippet over the phone. Sure enough, overwhelming public demand sent the song into heavy rotation, where it has stayed ever since.

That tidbit reveals much about why “Smells Like Teen Spirit” ultimately became a humongous hit and the defining anthem of the 1990s. Endless analyses have offered explanations ranging from Vig’s production and Andy Wallace’s mixing making Nirvana’s music more palatable to a mainstream audience, to MTV’s support of its music video, to the song simply existing at the right cultural moment. What commentators often overlook is the most basic and probably most accurate explanation. Put aside the radio-ready production, the generational ennui, the iconic pep-rally-from-hell promo — “Teen Spirit” grabbed the attention of listeners of all stripes first and foremost because it fucking rocked.

In an era when dance music and hip-hop were gaining huge ground, and the popular face of hard rock was ballad-friendly glam metal, Nirvana delivered a powerful demonstration of rock music at its cathartic, riff-driven best. The caliber of what the grunge trio had wrought was immediately evident to awed listeners even after a fleeting exposure to the tune, a true testament to the group’s songwriting ability and performance chops. Hell, if you cue up Nevermind right now, the sound of the full band kicking in nine seconds into that first cut will still feel like a hit to the stomach. That’s why 20 years later, the exhilaration of “Smells Like Teen Spirit” cannot be denied. — AJ Ramirez

2. “In Bloom”

Full disclosure: this writer is not a Nirvana superfan. But even as a casual listener, “In Bloom” has always been one of my favorite Nirvana songs (not to mention my favorite of the band’s videos—kudos to Cobain for allowing a little humor to seep into the mix). The track, one of the first recorded during the proper Nevermind sessions with producer Butch Vig, comes with plenty of fanboy lore: Vig removing—physically, razorblade and all—the song’s bridge from the final mix; Cobain taking, as Krist Novoselic put it, the hardcore edge off of the track and transforming it into a pop song; Vig’s ultimately victorious battle with Cobain to double-track his vocals for a smoother sound.

For those uninterested in backstory, the song delivers without it. Play it right after “Smells Like Teen Spirit” and it’s easy to see the same blueprint at work here that made that song instantly epochal—soft-loud dynamics, slow bridge, and thundering chorus. Even the basic elements are similar, with Novoselic’s simple bassline guiding the verse along until Cobain’s guitar slashes into the mix for the chorus. As ever, Dave Grohl provides the real muscle, with his flawless sense of build-and-release, completely unfussy in his fills and utterly economical in every flick of the wrist.

In other words, “In Bloom” succeeds so well because everyone in the band strips his own part of the composition down to the bare necessities. Novoselic may have complained that Cobain rid the song of its resemblance to Bad Brains, but the punk spirit is still here in full effect—no frills, just right to the point. Even Cobain’s brief solo is kept quick and clean, wasting no time on masturbatory wailing. There’s a reason why Nirvana inspired—as a rough guess—one billion kids to pick up a Fender guitar for the first time.

Of course, we also have Cobain’s lyrics, often a sticking point for me. There’s nothing quite as glaring here as “a mosquito / my libido”, but Cobain’s Yoda-speak in the chorus—”And he knows not what it means”—looks silly enough in the liner notes. But, all right, it works in the rhythm of the line when he sings it, and that’s enough. The song is prescient on two levels. It was written before the band became the biggest thing on the planet, and it anticipates Cobain’s discomfort with being singled out as the poet messiah of a generation of alternative youths and massive corporations, alike. And, yes, you have the whole “he likes to shoot his gun” bit, singled out in many a cautionary epitaph and half-baked news report in April ’94. Whatever—whether or not Cobain’s attempts toward lyrical indictment really fly or not, “In Bloom” rocks. You know? — Corey Beasley

3. “Come as You Are”

“Smells Like Teen Spirit” may have been the song that defined a generation, but you could argue that “Come as You Are” was better suited to be Nevermind‘s rallying cry. If nothing else, the title itself speaks to the ethos and ethics of the band, an almost tailor-made motto that described how Nirvana’s music embraced those who didn’t feel that pop culture and pop music gave them much to grab onto. You almost get the sense that Nirvana and the DGC marketing team may have felt the same way, considering that it’s the video for “Come as You Are” that works like the promotional cut for Nevermind, as it uses the album’s indelible artwork for its inspiration. Whether it was riding the coattails of the preceding single’s epochal impact or a standout a-side in its own right that gave Nevermind legs, the second single off of the album goes into the history books as Nirvana’s only other Billboard Top 40 entry.

Musically speaking, “Come as You Are” stands out in the Nirvana songbook as perhaps the group’s catchiest offering. Rounding off the manic energy of “Smells Like Teen Spirit” while creating its own sense of drama through Nirvana’s trademark stop-start dynamics, “Come as You Are” showed off Kurt Cobain’s pop chops better than anything else on Nevermind, and maybe even in the group’s entire catalog. Nothing illustrates this better than the family resemblance between the song’s signature aquatic-sounding guitar intro and the main riff of Killing Joke’s “Eighties”, which, as legend has it, gave Nirvana and its label cold feet over releasing “Come as You Are” as a single.

But in comparison, it just goes to show how Nirvana had an intuitive knack for melody that eluded the punk and noise-rock bands it considered its influences and peers. Sure, you can almost feel the heft of his guitar lines and there’s a coating of abrasive buzz in the careening solo, but Cobain’s guitar work always remains accessible and tuneful on the track. Almost finding a sense of harmony and peace in the eye of the sonic storm, “Come as You Are” speaks to Nirvana’s gift for taking hard, obscure sounds and turning them into something almost listener-friendly without losing any of its edge.

Likewise, Cobain’s lyrics end up being anthemic almost in spite of themselves. It’s almost too easy to claim that the opening lines — “Come / As you are / As you were / As I want you to be” — must be tongue-in-cheek, coming as it does from a band of misfits who had the responsibilities of representing a generation foisted upon them. But the real irony of the situation was that the song became a straight-up call-to-arms for outsiders looking for something to believe in and belong to: When it came to the way Nirvana was rapidly transforming the music industry and popular culture, Cobain couldn’t have uttered truer words than “The choice is yours / Don’t be late”. As circumstance would have it, though, those don’t end up being the pithiest lines of a song that, in retrospect, gives you a little too much to chew on and read into when you hear Cobain sing “And I swear that I don’t have a gun / No, I don’t have a gun”, in what now sounds like a ghostly voice. Ultimately, “Come as You Are” works as a fitting testament — however unintended and unwanted a tribute it may be — to the complexity and sphinx-like nature of Kurt Cobain as a performer. — Arnold Pan

4. “Breed”

Reading old reviews of Bleach offers the impression that just about anyone who heard Nirvana’s debut assumed the band was destined for bigger and better things. It’s an album that’s a little rough around the edges, but there are a few pop hooks, and the benefit of hindsight allows us to see that the band was a slick mix away from a bona fide hit. Still, there must have been people out here who thought Bleach was perfect the way it was, because while 40,000 copies pre-Nevermind isn’t a huge number, you still don’t sell that many albums without someone thinking you’re great. For those fans, the first three tracks of Nevermind must have felt like a cold shower.

“Breed” turns the heat back on. Really, it’s the rhythm section that’s the star of the show here. Dave Grohl is allowed to put together one of those ridiculously fast, rolling rhythms that remind the listener just how incredible a drummer he happens to be, while Krist Novoselic’s buzzy bass is what keeps the song from sounding like straight-faced punk-metal. The effect of Novoselic’s seven-notes-and-repeat bassline is pop via surf-rock, the drive that motivates Kurt Cobain’s repetitive verse and almost hypnotic coda. Novoselic is steady as a surgeon here, only changing things up when the chorus hits to follow along with Cobain’s chord changes — his refusal to change even when Cobain is screaming his loudest is emblematic of his less-is-more approach to his music, tying the verse to the chorus and avoiding a jarring transition.

As much as Nirvana tends to be synonymous with Cobain, he is in turn content to let Novoselic and Grohl do most of the heavy lifting on this one, as his words are essentially filler, something for the people to sing along to as they bop along to the beat. You could look into this one and find any number of meanings. “I don’t care if I’m old”, when isolated, seems oddly prescient now, but following it up with “I don’t mind if I don’t have a mind / Get away from your home / I’m afraid of a ghost” renders it essentially meaningless. It’s classic Cobain when he doesn’t really have anything to say: string some words together and figure out what they mean later.

The chorus, however, sounds like a desperate plea for wedded suburban bliss: “We could plant a house / We can build a tree… She said”, he sings, and the rage and urgency in his voice doesn’t imply that he agrees. Again, “suburban life ain’t for me” isn’t exactly the most original of themes, but at least it makes coherent sense. Just for good measure, Cobain drives “she said” into the ground, just to make sure the listener doesn’t ascribe the sentiment to him.

Still, he or she doesn’t have to. “Breed” is about speed and power more than anything Cobain might have been singing about, and Grohl and Novoselic are more than happy to take over for a track. It’s the perfect cut to put between “Come as You Are” and “Lithium”, a palette cleanser and a throwback to Bleach to prepare the listener for the album’s bleakest track. — Mike Schiller

5. “Lithium”

“Lithium” adds a dimension of twisted spirituality to Nevermind, as Kurt Cobain tells the tale of a devout cult member who, according to the author, turns to religion after the death of his girlfriend “as a last resort to keep himself alive. To keep him from suicide.”

Like much of Nevermind, “Lithium” flickers between loud and quiet. “I’m so lonely / And that’s ok / I shaved my head / And I’m not sad”, softly cries Nirvana’s frontman with all the discipline of a dedicated cultist who has seemingly found a kind of sense in his once chaotic life. The hook, however, is a full-on rallying cry as Cobain inhabits the same youth-stirring guise he took on “Smells Like Teen Spirit”. Unleashing the pent-up angst of Generation X — which he would soon be lauded as being the voice of after the album’s release—the singer’s shrieks of “I love you”, “I miss you”, and “I kill you” are met with determined yells of “I’m not gonna crack”, making it one of Nirvana’s most anthemic compositions.

But for all its heavy imagery, “Lithium” is one of the most pleasurable pop songs the band ever recorded. When brought in to produce Nevermind, Butch Vig’s first act on the song was to simplify the bass and drums sections. Vig’s production sparkles, from Krist Novoselic’s neatly-plucked bass to Dave Grohl’s spotlessly thumped drums and Cobain’s smooth guitar playing on the hook. In this respect it’s perhaps the album’s most obvious example of the polished production Cobain expressed feeling somewhat awkward about.

It wasn’t all that surprising then that at a recent club night I attended that promised “commercial chart R&B” spun by actor and celebrity DJ Idris Elba, “Lithium” was slid onto The Wire star’s playlist. If Cobain was alive today, a reflection on the song’s journey since his death no doubt would have irked him further. — Dean Van Nguyen

6. “Polly”

An idea can find its way through history and into a song without the songwriter knowing it, and that’s what may have happened on “Polly”. Though Kurt Cobain was introduced early on to the music of Leadbelly (a man he often called his favorite performer), there’s no certainty that he was well-versed in folk songs. Regardless, when he chose the name Polly, he set off a chain of connections, one that literally crosses an ocean of history.

Cobain wrote “Polly” after reading about the victim of a 1987 kidnapping and rape case in Tacoma, Washington. The teenage girl, whose name was not disclosed, was abducted, raped, and tortured with various devices including a propane torch before she managed to escape. That’s the gist of the song’s creation, but its ideas echo the traditional murder ballad “Pretty Polly”, performed by Dock Boggs and others like Rory Block, the Stanley Brothers, and B.F. Shelton scattered throughout the years. That story finds its first chapters in a broadside called “The Gosport Tragedy” circulated in London as early as at least the early 18th century. There, Polly is named Molly (both are diminutives of Mary). Pregnant, she is killed by William, the father of her child. She hunts him down on board a ship at sea, appearing as a flaming bird, and forces him to confess. In a later version, she rips him in three.

The ship continued across the ocean, carrying the song, and while the motive for the murder remained, the supernatural element disappeared before the vessel even landed. In the 19th century, the song and the archetype of Polly split and regenerated. In some versions, Polly is resourceful, intelligent; her story changes. In others, she is naïve and waif-like; her story stays the same. In Boggs’ performances, instead of being killed, Polly “[goes] to sleep”, which tells us more about the narrator in the song than it does Polly. As cultural historian Greil Marcus has noted by way of novelist Sharyn McCrumb, the motive for Polly’s murder—her pregnancy—disappears in many 20th century versions, befitting a frenzied century of casual violence. Only a few modern variations include her killer being brought to justice. The story keeps eroding down to its violent core.

In the scabbed performance on Nevermind, Cobain chooses the Polly that is resourceful, the girl who “amazes” the narrator with her “will of instinct”, a phrase that leaps out of the song. The rapist in the song is amazed because his imagination, though animalistic, is limited and destructive; he cannot understand the strength of her will to live, and it forces a new vocabulary out of a man who has muttered the rest of the song in fragments. In most contemporary versions of “Pretty Polly”, William pulls the surprise, revealing the “fresh dug grave and the spade lying by”; here, Cobain inverts that surprise, rebuilding from the song’s core, rebuilding the core itself.

Cobain sings through the man’s point of view in order to condemn it. You hear this in the lyrics—how Polly says she’s “just as bored” as him, an insult to his intimidation and abuse—and in Cobain’s performance, originally recorded in 1990, a year before the sessions which formed most of Nevermind. Coming after “Lithium” and slightly echoing its opening riff, “Polly” tricks you into thinking it’s going to be more of the same. The acoustic guitar is scraped and low, set back from the mic. Chad Channing’s cymbal crashes at the head of each chorus hint that the band might come in, but it never does; “Polly” remains one of only two all-acoustic songs on the album. Cobain’s voice is boyish, less innocent than it is defensive, but the tone is blank enough to forbid any hint of humanistic empathy with the narrator, any sense of reversed victimization or glorification of what he’s done. He is—as Cobain wrote in the liner notes to Incesticide, describing two men who sang “Polly” while raping a woman—a “waste… of sperm and egg…”

Whether Cobain knew exactly what connections he was calling forth when he used the name Polly is beside the point. He knew enough. — Robert Loss

7. “Territorial Pissings”

I wholeheartedly confess to being one of the few who never liked Nevermind. The record’s guitars blazed too brightly, the drums seemed just a tad too restrained, and the bass didn’t quite scrape the bottom of the low end like I would have liked. Twenty years later, I haven’t changed my mind much on these matters. However, I maintain that “Territorial Pissings” remains the best track on Nevermind, because it obviously took my expert criticism to heart. Thanks, fellas!

Obviously, Kurt Cobain’s suicide has cast a long gloomy shadow over the band’s reputation. The thing is, Nirvana was a hilarious band. Not always. But quite often. Lest we forget the venerable “Sliver”, the “In Bloom” video, the sensational bass toss at the 1992 MTV Video Music Awards, and, eventually, the wacky “tourette’s”, there’s this—a maniacal punk song that begins, of all things, with a seemingly drunken nod to the hippy-dippy Youngbloods. On the one hand, this allusion is appropriate; Kurt Cobain was not particularly shy about expressing an affinity for folk as well as for punk rock. On the other hand, it comes off as the embodiment of punk’s basic aspiration: running the paisley flower power of the 1960s, as well as the bloat of the 1970s, through the bandsaw of cynical, sneering guitar rock. If “Territorial Pissings” does anything, it cuts like about a thousand knives.

Over the course of the song’s shambling two minutes, Cobain spits typically inane, but brilliant, lyrics: “Never met a wise man / If so it’s a woman”; “Just because you’re paranoid / Don’t mean they’re not after you.” The chorus rings out like a desperate plea for most of the track: “Gotta find a way / A better way.” But then, in the final moments, the refrain collapses on itself, degenerating into a brief series of crazed shrieks before, well, suddenly stopping. It’s these final few seconds that make the entire song, if not the band’s entire career.

A quick scan of this track’s YouTube commentary reveals that people still think that music this aggressive must find its resolution in violence—actual non-metaphorical violence. It doesn’t. Here, in the territory that Nirvana cordoned off, the wise ones are women, not men like, say, Axl Rose. Here, the transcendent thinkers are aliens. And here, the endpoint of full-throttle rock music is the hilarity of howling aloud as the tune disintegrates. That’s punk rock, because, really, anyone can do that. All of those things comprise the better way. The better wayayayayayayyyyyy! And if you don’t like any of that, get the hell off the lawn. — Joseph Fisher

8. “Drain You”

Always a bridesmaid, never a bride. It’s a tough gig being the b-side to the biggest rock song of the decade. And no, “Drain You” is not “Smells Like Teen Spirit”, but in a lot of ways, it’s more interesting. If “Smells Like Teen Spirit” is an exercise in economy, with every note and beat perfectly placed, “Drain You” sees Nirvana indulging itself a bit more (though Nirvana’s indulgences still make anything done by its bloated 1970s godfathers seem like Philip Glass). We get an honest-to-god bridge, longer than two bars, with weird noises and gloom-and-doom atmospherics. The track also subtly breaks free from the Nevermind pattern of soft-verse, loud-chorus. “Drain You” goes something like this: loud, then loud, and loud (well, except for that bridge). It’s the song the flannelled faithful could play for any naysayers who accused grunge music of too much moping and not enough rocking.

What makes “Drain You” a real standout are Cobain’s lyrics—still a little hammy and a little obtuse, the chorus lets the King of the Earnest try for tongue-in-cheek. “Chew your meat for you,” he sings, “Pass it back and forth / In a passionate kiss / From my mouth to yours / I like you.” Here’s a test to see if your rock music is doing what it should do. Recite the lyrics out loud. Imagine you’re saying them to your grandmother. Is she disturbed about your generation? Good. Carry on. Cobain’s imagery is wonderfully gross, embracing silliness rather than shooting for dour sloganeering. And, wouldn’t you know, he manages to hit at something genuinely sweet and affecting, in a strange way. “Drain You” hasn’t become celebrated as one of the alterna-’90s’ greatest articulations of love, but perhaps it should. It nails the decade’s supposed tone perfectly, with enough irony to make the image stick in some folks’ craws, but not enough to overpower the little bit of prettiness at its emotional core.

But that’s not what people wanted from Nirvana, by and large. Instead, Cobain was allowed to fill the role of heart-on-sleeve, tortured guitar hero. It’s a shame — the guy clearly had a great sense of humor. Nevermind accomplishes many things, but making you chuckle isn’t high on the list. “Drain You”, when stacked up next to “Teen Spirit” or “Something in the Way” or “Come As You Are”, seems thoroughly fun in a way that the album’s other tracks simply do not. The song still delivers the same adrenaline rush as the band’s best full-volume material, but it does so while feeling less heavy, less grave. It’s an interesting reminder to the band’s detractors that Nirvana was not always so monolithically melancholy, after all. — Corey Beasley

9. “Lounge Act”

Take a suburban male, 12 or 13 years old, who has found Nevermind (this scenario takes place in 1991, of course). Kurt Cobain speaks to him in a way no other artist has, offering disdain for the world around him, rage to those closest to him, and the sort of sense of humor that means you can never quite tell whether he’s joking. Nirvana’s music is the sort of thing that really means something when you’re that age, even if what it means isn’t entirely clear.

Still, the complexities of Cobain’s lyrics can be difficult for that same teen to digest. Double meanings, interpretation — these are things for poetry class, not suited to the sort of cathartic release that the music would seem to suggest. This is why “Lounge Act” needed to be on Nevermind.

Far from the throwaway track that its short length, late placement, and simple structure would imply, “Lounge Act” is the most immediate and accessible cut from Nevermind. It’s about a girl. Or, maybe, it’s about two girls. Most likely, it’s about the idea of girls; it’s about the difficulty and futility of romance, with some concrete examples to draw on for inspiration. When that suburban teenaged boy is experiencing the sort of frustration that draws him to Nirvana, chances are he’s having trouble in the romance department. While other tracks on Nevermind deal with companionship in other, more abstract ways, “Lounge Act” takes it on directly.

“Truth, covered in security” is the lyric sheet’s reading of the song’s first line, and that alone offers the idea of honesty as a fungible concept. If you’re not reading the lyric sheet, though, you could just as easily hear “insecurity” as one word, which changes the meaning to something more immediate, something you do when trying to navigate a social setting rather than a more general commentary on honesty. It’s the brilliant sort of stage-setting first line that Cobain had a knack for making look easy, and the rest of the song jumps off from there, traveling quickly from the narrator’s insecurity to anger at the target of his affection.

“I’d like to but it couldn’t work”, he says, giving up before he even tries, at least until he gets desperate: “I wanted more than I could steal / I’ll arrest myself, I’ll wear a shield,” he sings, and it even seems like he wins… until he turns jealous (“I’ll keep fighting jealousy / ‘Til it’s fucking gone”) and she goes ahead and… well, whether she actually cheats is left open to interpretation, isn’t it? “I’ll go out of my way to prove that I still / Smell her on you,” he sings, and as he’s throwing accusations at his lover, it’s not clear whether her affair is real or whether it’s in his head, a product of insecurity and paranoia. This is, after all, the persona he’s built for himself for the previous eight songs.

While it would be folly to say that the average teen can truly understand what was going on in Kurt Cobain’s head, a song like this makes it easy to at least identify with him a little bit. “Lounge Act” humanizes Cobain like no other track on Nevermind. — Mike Schiller

10. “Stay Away”

Revolutions often span generations and are not often easy to describe in a few words. Some of the greatest counter-cultural documents, however, didn’t need several hundred page books to get their points across. The Communist Manifesto, for instance, only runs 23 pages. Nirvana, as influential as it is, may not be anywhere near as philosophically or ideologically influential as Marx and Engels, but what they share with the famed German philosophers is their brevity. In a brief, three minute and thirty-two second package, Nirvana succinctly gives a message to all of the copycat bands and to all of the critics who had passed over the greatness of the Seattle grunge scene: “Stay away!”

A classic Lebowski-ism applies perfectly to the song: the beauty of it “is in its simplicity”. The chorus, comprised of the eponymous charge, is a deeply effective summation of the rebellious tone that drove not only the music of Nirvana, but much of early 1990s grunge music as well. For Cobain, two words are all that is necessary to get his point across, and given the determination in his yells, he succeeds. The verses, punctuated by sharp stabs of distorted guitar, highlight much of what Nevermind seemed to be reacting to: Cobain calls out those who would “rather be dead than cool” and how with much music, “every line ends in rhyme” (which, perhaps ironically, then contributes to a slant rhyme in the next line). The music itself, of course, never lets up; beginning with a snare drum and a bass, the song then kicks into overdrive, with the sludgy distortion of Cobain’s guitar emphasizing the band’s rebellion.

Though the song spends much of its time in aggression towards the things that it rallies against, it interestingly enough never gets violent. Instead of inciting action, violent or otherwise, toward the musical trends that led up to the release of Nevermind (synthesizer-driven pop and soft rock, most notably), the band merely insists that those detractors come no further. Given the resolve the band shows on this track and the rest of the record, it’s no surprise that the trio is quite aware of its strength and fully conscious of its likely implications.

With the spirit of rebellion against the mainstream of the time so prominent in this song, it’s ironic that Nevermind would lead to both grunge music and Nirvana’s stardom. Seeing as the anti-establishment sentiments of genres like grunge are often seen as vogue, as means of “being cool”, a cynical retrospective analysis might lead some to think that Nevermind was just a sly, two-faced means of achieving stardom. One listen to a track like “Stay Away” should dispel any such notion. There have been many great grunge artists since Nirvana, but there’s no record quite like Nevermind, and no song on that LP demonstrates both Nirvana’s skill and counter-cultural musicality better than this one. — Brice Ezell

11. “On a Plain”

“On a Plain” is a quilt of rags without pretense; you wouldn’t find it hanging in a gallery as outsider art. After the skuzzy guitar junk at the track’s opening, the song steps forward like it has work to do. In many ways, it’s a working-class song.

It’s also a very self-conscious song. The bracing assertions of the music are countered with anxiety about its lyrics and the audience and singer’s need for sense. Cling too much to one thread, though—for instance, “I got so high, I scratched ’til I bled”, probably a reference to heroin use—and you’ll strain yourself trying to tie it to others. Cobain often wrote by cutting out and stitching together lines from his poems and early song drafts, including the line above and “The black sheep got blackmailed again” from an early version of “Verse Chorus Verse”. In some songs, you’d never know that; here, the song is certain you already know.

If the protagonist in this track could do better, he would. He’s tried, starting “without any words” because words just confuse. Some lines hold together, others are just bad wordplay (that one about sheep and the clumsily-phrased line about forgetting the zip code). An enormous amount of ambiguity is in the couplet “It is now time to make it unclear / To write off lines that don’t make sense”. Well, if you want to make sense, you would dismiss certain lines. Unless he means “write off” as in dashing off a couple nonsense lyrics (early on, Cobain tended to write lyrics in the studio just before a vocal take). Or is it “off lines”, as in strange verse? If you look at this song as long as the singer has lived it, you’ll get lost.

“On a Plain” embodies the complex mix of self-loathing, apathy, confusion, self-consciousness, and boredom that “Smells Like Teen Spirit” sings about. That song stares outward, seeing those qualities mainly in culture; “On a Plain” sees them within. Though faster than “Smells Like Teen Spirit”, the song feels slower, stoned, resigned to its verbal failures. “What the hell am I trying to say?” Cobain asks only once; much more often he just sighs, “I’m on a plain / I can’t complain.” It’s the track’s equivalent to “Oh well, whatever, never mind.” The flatness of the plain makes everything alike, which makes everything meaningless.

And yet “On a Plain” is one of those Kurt Cobain songs that encloses an infectious, simple melody within a pleasing sameness and tense indifference. That complexity in his songwriting is, I think, often overlooked. So are the songs’ intelligence and honesty. Here you have a man singing, “I love myself better than you”. The narrator’s admission in “On a Plain” isn’t nihilistic or cynical, it’s candid. Plenty of pop and rock songs have said that without meaning to (legions of them, actually). Few mean to say it. Even fewer combine the morality and aggression of the next line, “I know it’s wrong, so what should I do?” Yeah, got any ideas? You and I aren’t exactly Mother Teresa.

All of this is happening despite “On a Plain” exemplifying the pop sheen that detracts from Nevermind. Cobain’s lead vocals are flattened and Dave Grohl’s backups sound synthetic, turning “love myself better than you” into a bratty boast (the upcoming re-release’s inclusion of Butch Vig’s original mix of the album may remedy this, but plenty of live versions unleash the idiosyncrasies in Cobain’s voice). I’ve listened to this song for 20 years and still wonder if Krist Novoselic really plays on it except for that break at the end of the bridge. Full of space but without depth, the wall of bright guitars turn the inwardness of the song back out. It worked for radio. You can imagine those final “uhnn-uhh”s leading into a DJ’s brassy bass voice, but they sound like a pathetic attempt to sex up what has been a blunt song about, at the very least, a communication disorder. Nirvana never sang them live.

It doesn’t matter much. You can still hear the rags. That’s how good this performance is. — Robert Loss

12. “Something in the Way”

Interestingly enough, the most mellow, relaxed song on Nevermind is the same track that producer Butch Vig called the hardest song on the album to record. Cobain wanted the track to be as quiet as they could possibly make it, emphasizing the song’s mournful melancholy. And after the eleven songs prior to it, “Something in the Way” is very much to be worth the effort that Vig and the band put into recording it. The acoustic guitar-backed “Polly”, while also a break from the sludgy distortion dominating the record, has nothing on the somber beauty of “Something in the Way.”

Lyrically, the song has caused much speculation. Some people have suggested that the song’s tale of a homeless man living under a bridge is an autobiographical account of Cobain himself, after having been kicked out of his house by his parents. The lyrics could even be depicting a sort of doomsday prophecy, or even a tale of someone who fought against the mainstream and lost. Ultimately, it’s Cobain’s attitude towards the importance of lyrics that rings the most true whilst trying to interpret the song’s simple yet cryptic lines: music first, lyrics second. As interesting and interpretive as “Something in the Way” is, it’s the music that is at the forefront. Plus, with non sequiturs like “It’s okay to eat fish / ‘Cause they don’t have any feelings”, it seems more prudent to accept Cobain’s lyrical absurdities as ingredients necessary to the brilliance of Nirvana’s output instead of ciphers to be decoded.

The most well-known Nirvana songs from Nevermind are often the ones where Cobain is shouting; the oft-played “Smells Like Teen Spirit”‘s at times incomprehensible chorus being a prime example. What makes “Something in the Way” so starkly beautiful is Cobain’s vocal volume. Compared to his performance on the rest of the LP, he’s practically whispering. His acoustic guitar is so softly strummed that it sounds as if it was being recorded from several feet away. Like the eccentric bridge-dweller the lyrics depict, the song is something of a curiosity in the context of the rest of the record. The use of the cello is also unusual given the small instrumental setup for the rest of the record; even when Nevermind is at its most intense, guitar, bass, and drums are all that was necessary used to demonstrate that power. Here, the creaking cello provides a doomy background to the song’s chorus, adding to the album’s glum disposition in a darkly beautiful way.

Despite its curiosity, it remains one of the most poignant songs on Nevermind. The rest of the record’s reliance on the heavier elements of grunge allows “Something in the Way” to shine amongst a stellar tracklist merely by slowing the tempo down. Even though critics of Nirvana often point out how depressing the group’s music can be, too often they’re focusing on the guitar-heavy songs that most people know (and, of course, their criticism still remains reductive). Rarely do they take the time to look at tracks like “Something in a Way”, which, in its low-key moodiness, is the perfect conclusion to an album that, while not the most optimistic, is nonetheless beautiful in its own right. — Brice Ezell

13. “Endless, Nameless”

There was a pretty significant period of time in 1991 when I thought that “there’s a secret track on Nevermind” was an elaborate joke that my friends were playing on me. Still a bit stung by the revelation that spinning around and saying “Bloody Mary” ten times in front of my bathroom mirror didn’t actually reveal the mischievous spirit named in the chant, it seemed clear the first time I fast-forwarded “Something in the Way” and it just, you know, ended that my more knowledgeable friends were pulling my leg.

Turns out we were both right; “Endless, Nameless” didn’t get tacked onto Nevermind until the second pressing.

In all honesty, it’s probably better than I didn’t hear “Endless Nameless” for a while until after I had become intimately familiar with the rest of the album. Tucked away after ten full minutes of silence, its presence is a thing unto itself, a part of Nevermind only in that it shares disc space with the other 12 tracks. This is for good reason: “Endless, Nameless” is a sign saying “GO AWAY” spelled out in blood on an old wooden plank. It is ugly, it is messy, it is everything about Nirvana that Butch Vig and Andy Wallace washed away with their production and mixing.

You hear hints of this throughout Nevermind, but “Breed” is catchy as all get-out for all its volume and speed, and “Territorial Pissings” sounds like, well, a piss-take, a little too hard to take seriously. “Endless, Nameless” is raw anger without a sense of humor or any semblance of melody, just a few distinct sections that make sure that it sounds too calculated to be labeled as pure noise.

The story is that this song emerged after a particularly lousy take of “Lithium”, and as a way to exorcise the frustration of a botched performance, it’s pretty much perfect, something that allows the listener to hear a little bit of the behind-the-scenes. It exists as validation that the anger that streams through Nevermind is genuine, and that Nirvana’s three members had simply found a productive way to channel it.

The benefit of hindsight allows us to see a little more in “Endless, Nameless” than a simple curiosity at the end of a classic album. In Utero would show up a few years later, and it would shock its listeners with its dry, raw sound, a sound they’d actually heard before in this hidden track. You can hear pieces of “Scentless Apprentice”, “Milk It”, and “Radio Friendly Unit Shifter” in “Endless, Nameless” — In Utero found the band willing to work its more unpolished fits of rage into a set of songs that still had plenty of pop appeal. Even on that album, though, there weren’t any experiments this unfriendly, or even this long.

As much as “Endless, Nameless” says “GO AWAY”, then, it also says, “To be continued.” It may not always appear at the end of Nevermind, but when it does, it enhances the album immeasurably. — Mike Schiller