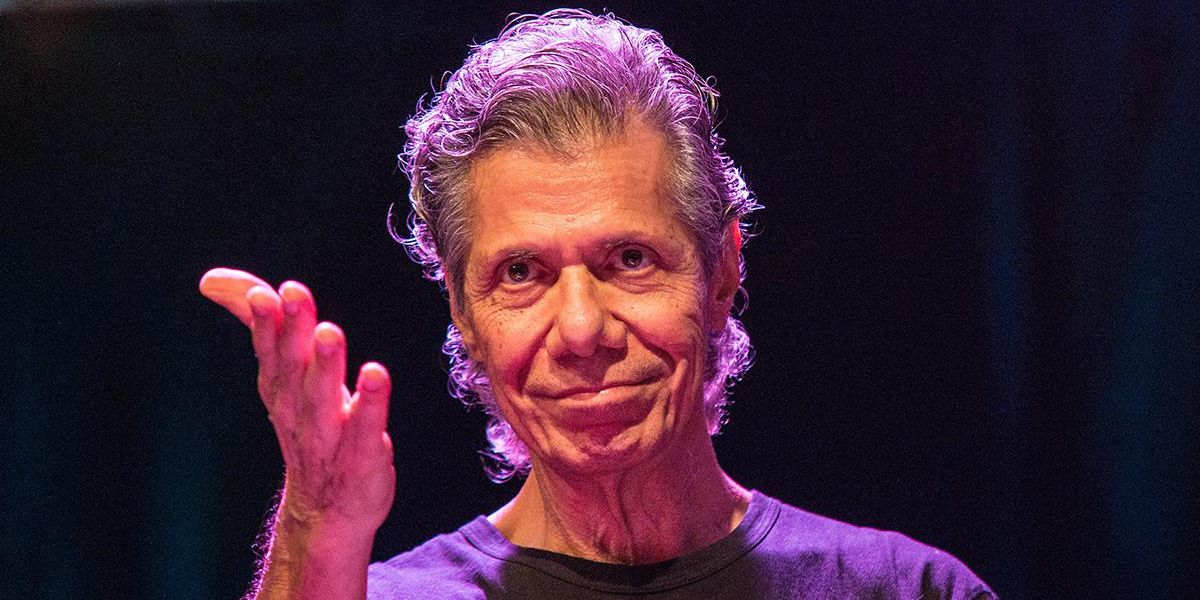

When the news arrived on Thursday that jazz pianist, composer, and bandleader Chick Corea had died of a rare form of cancer two days before, the music world was shocked. It was not just that Corea was a jazz “star” in an era when jazz was losing relevance, but that in his late 70s, he seemed more vital than ever. During the pandemic, Corea—already known as a collaborative and affable musician—was sharing his practice sessions online and reaching out to the world.

His eighth decade didn’t see him dialing back or growing more distant. After he released Chinese Butterfly in early 2018, he brought the band into small clubs such as Washington DC’s Blues Alley where you could sit five feet away from the master as he spun his lines. Chick Corea danced behind his keyboards even then, seeming ageless—a restless sprite with an incredible touch. When he turned 75, he played with 15 different bands for a two-week stint at the Blue Note in New York. He was a kid in a candy store or a sandbox. The name of his final album? Plays, of course.

His sudden absence is jarring because we expected to hear more of his signature rippling runs and harmonic brilliance. Corea was one of a quartet of extremely popular jazz pianists who changed the way music was played beginning in the 1960s. McCoy Tyner died less than a year ago, though he had not been active for more than a decade. Keith Jarrett only recently announced that a condition had forced his retirement from playing. Only Corea and his contemporary, Herbie Hancock, were still active.

Except for Tyner, who remained a jazz purist restricted to tonal post-bop jazz and acoustic instruments, Jarrett, Hancock, and Corea were all restless artists. Hancock fronted electric/funk bands and had a hip-hop hit with “Rockit,” and Jarrett made many classical music recordings and wrote orchestral pieces. Corea, however, was doing all of that and more. He was a fusion pioneer with Return to Forever and played avant-garde with Anthony Braxton and the band Circle. Corea composed classical works with and without improvisation, and he played duets with everyone imaginable (singer Bobby McFerrin, Italian pianist Stefano Bollani, Flautist Steve Kujala, many, many more). Also, Corea formed bands that played something closer to “smooth jazz” and bands that played hard-nosed modern jazz—and, somehow, everything in between.

Across 81 studio albums as a leader, another 25 live recordings as a leader, and then scores of albums as a sideman across his entire career, Corea was an unerringly superb pianist—a thrilling soloist, a propulsive and sensitive accompanist, and a band member even though he was a superstar. It is equally valid that, beginning in the mid-to-late 1970s, he recorded music that didn’t meet with critical acclaim in concept or historical taste. It was brilliant music, often, but baroque or super-glossy, punched up with string quartet or vocals or the new toys that Corea was still mastering: his banks of synthesizers. Just as the young Corea turned the Fender Rhodes electric piano into a highly expressive, singing instrument for jazz improvisation, he developed a unique synth sound as well—but that didn’t make the way he used the synth always artistic.

It could be hard to make sense of Corea as he straddled serious jazz and commercial styles — particularly once he started his popular “Elektric Band”, his discography is dominated by over-flashy fusion, mushy smooth jazz rounded corners, and unctuous saxophone lines. But Corea was making music that he seemed to love even when other critics or I didn’t. But how can we blame this incredible musician for experimenting with synthesizers at precisely the moment when the commercial bottom was falling out of acoustic jazz? Often enough, Corea still made it all beautiful.

Here, in chronological order (by recording date rather than release date), are my ten favorite Chick Corea recordings, spanning different eras of his astonishing musical life—though I think the best of the best was mostly recorded before the ’80s kicked in. I have also omitted some live recordings on which he performed widely with musicians through his career, summing things us. With a nod to my friend Eugene Holley, I recommend his dazzling The Musician from 2017, recorded live at New York’s Blue Note, featuring much of music and the collaborators detailed in my Top Ten.

1. Now He Sings, Now He Sobs (Solid State, 1968)

The Band: A piano trio with bassist Miroslav Vitouš and drummer Roy Haynes

Its Brilliance: After arriving in New York from the Boston area, Corea had been accompanying flutist Herbie Mann and vibes master Cal Tjader (both early proponents of how Latin grooves could animate more pop-jazz) as well as trumpeter Blue Mitchell and other post-boppers. But Now He Sings, Now He Sobs fronted his playing in the classic piano trio format and his own compositions. Haynes played with Corea in Stan Getz’s quartet and was an ideal partner—light and swinging but plenty aggressive—and Vitouš brought a Scott Lafaro-esque willingness to spar with Corea. Can an artist sum up their career in what was essentially a debut? Yes.

Brilliantly composed tunes (“Matrix”, “Windows”) appear next to collective free improvisations (“The Law of Falling and Catching Up”, “Fragments”) as well as one standard and one Thelonious Monk tune. There are moments when you can hear Corea’s penchant for dancing Latin rhythms burst through, even on this self-seriously modern recording. If the Bill Evans Trio records of the 1960s were a template for piano trios in the future, this was another one—seemingly neither over-indebted to Evans but also building on his shoulder. If you had to pick only one Chick Corea album…

Killer Track: “Steps—What Was”, which flies out of the gate as the opening track and changes the way you hear jazz piano. It’s that good.

Listen: Spotify

2. The Miles Davis Quintet – Live in Europe 1969 (The Bootleg Series Vol. 2) (Sony, 1969)

The Band: Miles Davis, trumpet; Wayne Shorter, saxophones; Corea; Dave Holland, bass; Jack DeJohnette, drums

Its Brilliance: Corea replaced Herbie Hancock in Davis’s scorching quintet just as the great trumpet player was shifting from standards to original super-charged post-bop to fusion music that added funk, psychedelia, and free playing to his aesthetic. The studio records of this time are rightly lauded, and Corea appeared with on Filles de Kilimanjaro, adding Fender Rhodes electric piano to the band’s sound. With In a Silent Way and Bitches Brew, Corea would be a part of the sound-shifting studio experiments Davis created with producer Teo Macero. Then Corea would be a part of the expanded-band live recordings where he can be heard dueling in the band with Keith Jarrett as a running mate.

But these recordings of the so-called “Lost Quintet” didn’t get officially released until 2013, though fans were passing this stuff around for decades. It’s marvelous, combining the tribal sound and freedoms that came with the big jam tunes with the quintet’s fleet individualism. Corea has a huge hand in creating this music—as you can hear the mixture of free playing and lyrical playing that he had been bringing to his dates at the time.

On these sides, we also hear his first encounters with the Rhodes, an instrument of which he would be an unquestioned master. He bends texture and touch to make this lunk of a piano snarl, coo, ring, and thrum. The audio is only so-so, but everything powers through, and Corea is heard in greater relief in the smaller band. They are abstract and grooving and avant-garde, but then there are moments of supreme and utter lyricism.

Killer Tracks: “Bitches Brew”, “I Fall in Love Too Easily”

3. A.R.C. (ECM, 1971)

The Band: A piano trio with bassist Dave Holland and drummer Barry Altschul

Its Brilliance: Given the size of Corea’s discography, it may be indulgent to include another early trio record, but Corea is now recording for ECM with three-quarters of the band Circle (without Anthony Braxton). All three players are ferociously creative, balancing lyricism and freedom, swing and open groove playing. Corea is a fully mature artist by now, coming out of the Davis band but not yet ready to make the leap to more fully “popular” jazz. Holland, his contemporary, is also a complete musician, about to create his own masterpiece, Conference of the Birds. Altschul didn’t become as huge a figure in the music, but the evidence here is that he is playing with peers, and his contributions are unique: a clattering soundscape that is less bound to jazz’s history-making it just right.

Killer Tracks: “Neffertiti” is the excellent Wayne Shorter tune, deconstructed here but recognizable, and “Vadana”, which begins with a set of phrases that could have been played on even the most accessible Corea recording but then unspools as a very open improvisation, shifting from ballad time to fast swing—all intuition and brilliance, Corea’s filigreed right hand-matched by a silvery left hand and Holland’s continual lyricism.

Listen: Spotify

4. Piano Improvisations, Vol. 1 (1971)

The Band: None—solo acoustic piano

Its Brilliance: The story is that ECM intended to record Corea and Jarrett in duet, but Jarrett demurred. The result was Jarrett’s Facing You and two volumes from Corea, each solo. All are wonderful. Corea’s ability to captivate an ear with lines that are both ornamented and extremely direct comes clear on the opening “Noon Song”. The music is light and often breathtaking in its transparence: holes of silence open up, and then melody rushes in to fill them. The songs themselves are wonderful, and we hear for the first time a Corea classic, “Sometime Ago”, soon to be recorded by the first incarnation of Return to Forever. In this solo performance, all the elements are present, with Corea using the piano like the orchestra it can be.

Killer Tracks: “Sometime Ago” and a cycle of “Where Are You Now” tunes that sound freely improvised yet lyrically appealing

Listen: Spotify

5. Stan Getz – Captain Marvel (Verve, 1972)

The Band: Stan Getz, tenor sax; Corea; Stanley Clarke, acoustic bass; Tony Williams, drums; Airto Moreira, percussion

Its Brilliance: Stan Getz knew his way around bossa nova and Latin jazz styles, of course, and was looking for a rhythm section for a tour that would get him back in the public eye. Corea had already assembled his first version of Return to Forever, built around the limber young bassist Stanley Clarke, saxophonist Joe Farrell, and two Brazilian musicians, the vocalist Flora Purim and percussionist Airto Moreira. Getz brought in the rhythm section, but he wanted a jazz drummer after some takes didn’t go well.

Corea added the Fender Rhodes electric piano to the band’s arsenal on the road, modernizing Getz’s sound as well as his book and his willingness to really bite at the music. The recital they recorded includes five of Corea’s most winning tunes, plus Strayhorn’s “Lush Life”—and it is the pull and tug between Getz’s traditionalism and the future-leaning of the band that makes every second of this date electric. Corea’s astonishing comping pushes Getz to feverish playing whenever possible, even though the leader’s tone remained lush.

Killer Tracks: “La Fiesta”, one of Corea’s most popular tunes, debuts here with galloping percussion and the too-rarely-covered waltz “Times Lie”.

Listen: Spotify

5. Light As a Feather (Polydor, 1973)

The Band: Return to Forever Volume One—Joe Farrell, saxophones and flute; Flora Purim, vocals; Corea; Stanley Clarke, acoustic bass; Airto Moreira, drums and percussion

Its Brilliance: Corea decided in the early ’70s that performing gnarly modern jazz was not for him—he wanted to reach an audience through music with more beauty and joy. And adding a more Brazilian dancing quality to his music made sense. Feather was the follow-up to the debut of this new concept Return to Forever. That gave a different gleam to “Captain Marvel” and “500 Miles High” from the Getz date, and added a version of Corea’s most often-requested song, “Spain”, which begins with a gloss on Rodrigo’s “Concierto de Aranjuez”. Purim’s vocal is a gauzy touch of genius, particularly paired with Farrell’s flute, and songs like “You’re My Everything” manage to come off as sultry, sophisticated, carefree, and joyful all at once. It sounds simple, but in fact, this material is almost impossible to do with such style and percolating lightness.

Killer Track: “500 Miles High” begins atempo, Purim floating delicately, and then it pops into a funky sway and gives Farrell space for a tenor solo that is his best moment. Corea’s comping beneath him, though, is worth the cost of the album (back when albums were purchasable things).

Listen: Spotify

6. Crystal Silence (ECM, 1973)

The Band: A duo with vibraharpist Gary Burton

Its Brilliance: Corea is one of the great duet partners in jazz history, but none of the duos is as compelling as his communion with Burton. Like Corea, Burton is a lyrical player of the highest order and has a knack for rippling phrasings that dance in a percussive manner. On ballads such as the title track, they leave open spaces that serve them well, and their busy and bouncy tracks (“Senor Mouse”, “What Game Shall We Play Today?”) generate the excitement of truly percussive music.

Hip rock fans (say, Frank Zappa partisans) heard rhythmic urgency but a level of harmonic sophistication that was rare in this kind of soulful jazz. It’s worth noting that the kind of super-precise playing we hear on “Senor Mouse” is delightful here and merely more bombastic and silly when such a tune was handed over to the second incarnation of Return to Forever, with Lenny White’s drums, Clarke’s electric bass, and Al Di Meola’s electric guitar playing the same stuff. It’s a useful reminder of how Corea could shift from one sound to another.

Killer Tracks: Steve Swallow’s “Falling Grace” always sounds good, but not always this good, and the title track, recorded often, is given its definitive reading—maybe there is nothing more mournful and beautiful in all of jazz.

Listen: Spotify

7. Romantic Warrior (Sony, 1976)

The Band: The electric Return to Forever band with Corea and Clarke (electric, mostly), Lenny White on drums, and Al Di Meola on guitar

Its Brilliance: Corea turned RTG into a jazz-rock “fusion” band after two recordings, keeping Clarke and bringing on Lenny White and a few guitarists, finally settling on the young Al Di Meola. The band made a series of fusion records that genuinely defined the space in conjunction with several other Miles Davis alumni. Hancock created his funky “Headhunters” band, and Tony Williams was fusing rock and fiery organ jazz in his “Lifetime” band. Wayne Shorter and Joe Zawinul created the famous Weather Report, which shifted over the years from a kind of electronic free jazz to a set of ingenious arrangements dominated by Zawinul’s keyboards. John McLaughlin made a few Mahavishnu Orchestra albums that put progressive rock and jazz in conversation.

The electric Return to Forever was the closest to the last of these in texture and approach but had the advantage of Corea’s compositions, which were catchy, grand, and fabulous vehicles for improvising. Romantic Warrior was the last album of this band’s run and the first that felt subtle and orchestral, magnificent, and sometimes bombastic. The synthesizers finally sound as rich and as artful as the writing (mostly), and the repertoire includes excellent tunes from the other band members. Both the best track, an all-acoustic groover called “The Romantic Warrior”, the most complexly absurd one (“Duel of the Jester and the Tyrant, Part I and III”) are Corea’s, which sums it up.

Killer Tracks: Lenny White’s “Sorceress”, which features lovely lines for Rhodes and synth but then gives Corea a pungent acoustic piano solo; the breathtaking title track.

Listen: Spotify

8. Friends (Polydor, 1978)

The Band: A quartet featuring Joe Farrell’s reeds, Eddie Gomez’s acoustic bass, and Steve Gadd on drums.

It’s Brilliance: By the late ’70s, Corea was famous for but done with Return Forever. He had just created four big concept albums in My Spanish Heart, The Leprechaun, The Mad Hatter, and Secret Agent each of which was loaded up with strings, horns, vocals, and thematic business. It would become a pattern for Corea that, at just such moments, he would lean back to a recording more firmly rooted in straight-ahead jazz. Friends gets mocked for its cover featuring four Smurfs, but the covers with Corea posing as a secret agent, a Lewis Carrol character, and a Leprechaun are significantly worse.

Friends‘ music is gorgeously relaxed and rich, largely swinging melodic jazz that features both piano and Rhodes, both saxophones and flute. Farrell’s soprano solos are distinctive and airy, and Gomez’s beautifully recorded bass solos are worth the entire album, singing in the instrument’s upper register most often. And then there are the Corea compositions: no dueling jesters or grand build-ups, just attractive melodies that enrich the listener without requiring that she or he have a tolerance for the boldest post-bebop adventures.

Killer Tracks: “Waltse for Dave” was surely written for Brubeck and is marked with his easy charm. “Samba Song” contains a fair number of tricky parts/sections and might have been a bombastic Return to Forever foray but, instead, is just exciting modern jazz. Which, frankly, is better, particularly when the grooving section starts and Farrell digs in on tenor sax.

Listen: Spotify

9. Three Quartets (Stretch, 1981)

The Band: Another quartet, of course, with Gomez on bass, Gadd on drums, and Michael Brecker’s tenor saxophone

It’s Brilliance: Now on his own record label, Corea continued to toggle between more traditional (“serious”?) jazz projects and music created for a larger audience. The original release’s compositions were three “quartets” meant to be like Bartok’s body of classical “quartets”. This is the Friends band but made more weighty with Brecker’s keening tenor being central to each track and no electric piano. The four original tracks (one dedicated to Ellington and one to Coltrane, serious business, like I said) were mainly muscular and intelligent, full of memorable riffs that link together in cascades.

“Quartet No. 2” uses a lovely section for solo piano to connect different elements, and the four voices are all orchestrated with more care than is typical for a jazz blowing date for a quartet. All that said, the session is loose too because the band is brilliant. For fans of Steve Gadd’s drumming with bands like Steely Dan or Paul Simon, here you get to hear him as a real jazz player, but one with an incredible ability to hit pockets. The session’s loose/relaxed nature is clearer on the reissue, which included four additional performances that are, well, more fun. That consists of a cool reading of Charlie Parker’s “Confirmation” that is a razzle-dazzle duet for just Brecker and Gadd, which I imagine that both saxophonists and drummers still haven’t fully recovered from.

Killer Tracks: “Hairy Canary”, a Corea bebop line that delights, and “Quartet No. 2, Part 1 (Dedicated to Duke Ellington)” with its long solo-piano introduction and then a breathtaking melody for Brecker.

Listen: Spotify

10. Remembering Bud Powell (Stretch, 1997)

The Band: Wallace Roney, trumpet; Kenny Garrett, alto saxophone; Joshua Redman, tenor saxophone; Christian McBride, bass; Roy Haynes, drums.

It’s Brilliance: Starting in the mid-1980s, Corea recorded six times with a new fusion group he called “The Elektric Band”—all for the label GRP, where smooth jazz had made a comfy home. There are fans of this music, which can be compelling and professional, but was also doused in MIDI synth sounds, drum programming, and candy-tone saxophony. Corea seemed to know that a steady diet of this stuff was nutritious for his bottom line but not for his soul because he simultaneously recorded and toured with an “Akoustic Band” that was a trio, doing standards and straight-ahead repertoire. The playing was sharp, but the band (particularly drummer Dave Weckl) was not subtle.

So, without adding an out-of-place “K” to the titles, he played some neo-traditional dates, as befitting a decade when Marsalis-led revivalism was both a trend and tonic. Corea recorded solo piano records of standards that were exceptional, he reunited his old trio, and he continued to collaborate with Gary Burton. But this date stood out, as he challenged himself with tunes by or associated with one of his critical influences and with a group of shining younger players (and Roy Haynes, who seemed to be getting younger every year). It is a bebop date, yes, but all the players are playing in late-century individual joy. Corea’s pianism is best of all, sometimes slightly raggy, other times Monk-ish, always cliche-free.

Killer Tracks: “Dusk in Sandi” for just the trio. An uptempo “Tempus Fugit”. A solo-piano “Celia”.

Listen: Spotify

11. Change (Stretch, 1999)

The Band: A sextet Corea called “Origin”, with Bob Sheppard and Steve Wilson on woodwinds, Steve Davis on trombone, and a new rhythm section featuring Avishai Cohen on bass and Jeff Ballard’s drums

It’s Brilliance: The Akoustic Band didn’t use electronics, but it always felt like a stunt—Hey, these fusion guys can play real jazz too! (They could, of course, but the playing didn’t sound organic.) The rhythm section for Corea’s new band, Origin, was heaps better, and they would play together as a trio too, making some excellent records. But the one Origin studio record is a lost classic. Wilson and Sheppard played clarinets (Bb and bass), flutes, and all the saxophones. Wilson gave the band a darker bottom as well, allowing Corea’s superb tunes to be colored in pastels as well as acrylic—and no chilly synth shiver was there to make the band sound arena-ready. Change was precisely that, enlivening Corea’s writing and sense of orchestration while still allowing him to indulge in the delights of dancing rhythms (“Armando’s Tango”) and lyric flight (“The Spinner”). For all of Corea’s toggling from fusion back to straight-ahead acoustic jazz over the years, this was the most compelling and original.

Killer Track: “Awakening” with its propulsive piano/bass unison lines and driving groove beneath a muscular head. It’s the kind of music that does not immediately obviously sound like Corea recreating his own sound, except that he could have only written it.

Listen: Spotify