Bassist and composer Charles Mingus used to be a figure of controversy for ten different reasons, some political, some personal, and—though this all seems silly in the new century—some musical. Mingus could be difficult with audiences, tough on fellow musicians, and intolerant of racist figures like a certain Arkansas governor who graces the title of Mingus’s “Fables of Faubus”. Looking back, Mingus—garrulous as he was—seems utterly on the mark.

Still, it remains historically true that his early 1960s “Workshop” band featuring firebrand reed player Eric Dolphy caught plenty of people by surprise. Mingus clearly prized Dolphy’s highly vocalized playing on alto saxophone and bass clarinet, and Dolphy joined the band’s 1964 tour of Europe, after which he planned to stay on the continent for good. (Famously, Dolphy died from complications or mistreatment of diabetes shortly after this tour.) Mingus wasn’t bothered in the least by the fact that Dolphy’s playing was considered too avant-garde for some of his fans or critics. It was an expressive blend of bebop grounding, vocalized squeaks and leaps, and thoughtful playing outside the standard jazz harmony—Mingus understood it from every angle.

The first performance from the band’s April 1964 concert in Bremen, Germany, is a basic blues line, “So Long, Eric”, that sums things up pretty clearly. Dolphy was wild, daring, traditional, grounded in blues and bop, yes. And he made the bands he appeared in bracingly better.

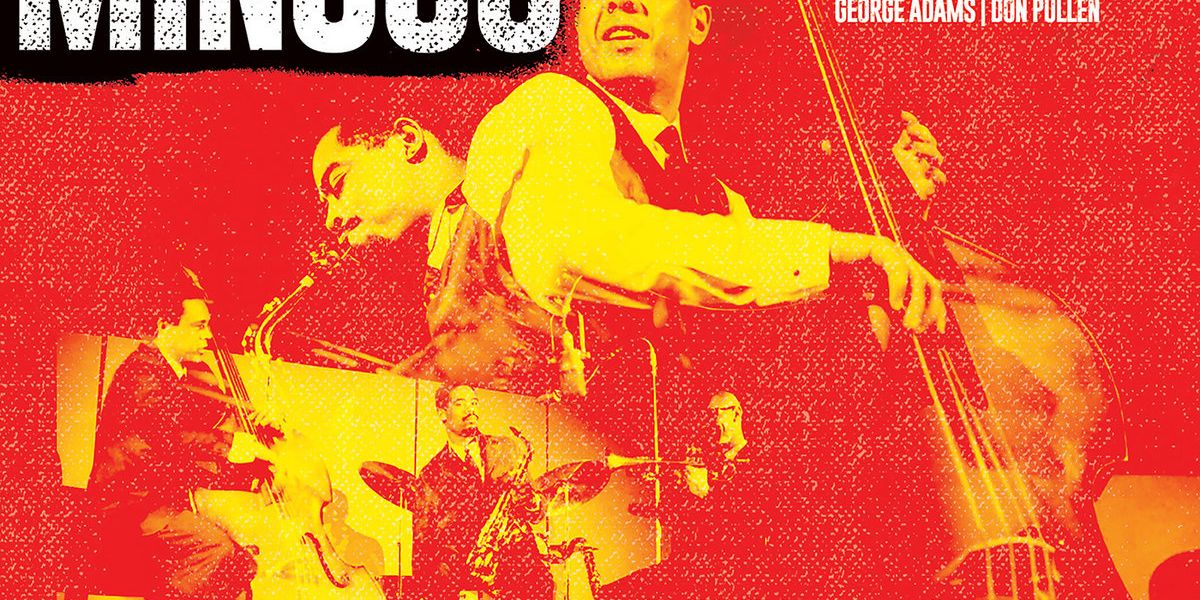

Charles Mingus @ Bremen, 1964 & 1975 newly releases the tapes of that concert and pairs them with a Mingus concert in the same town from 1975. The second concert features a substantially different band that was playing beautifully in the same tradition. Both sets, presented across four compact discs, present a rendition of “Fables of Faubus”—and deeply expressive playing and improvised music-making of the highest order.

According to the notes accompanying Bremen, 1964 & 1975, the audience of the 1960s was somewhat shocked and upset at Dolphy’s playing and Mingus’ engagement in this kind of “free” or “new thing” playing. By 1975, with this music fully absorbed by jazz audiences, they were more appreciative. That may be, but hearing the music in 2020, it’s hard not to shake our heads at the joy and dazzle in all of the music, with the 11-year separation seeming hardly significant. Yes, they are very different bands, but they both suggest—magnificently—how the music of 2020 would seamlessly integrate bebop tradition with more free playing.

Listening to “So Long, Eric” as the 1964 set-opener, it’s hard not to note that Dolphy is hardly the only member of the band who is cutting loose and playing with some growing distance from standard bebop. Trumpeter Johnny Coles is tart and tasty, yes, but he moves into some delicious odd notes and uses an approach just as vocalized beyond “proper” technique as Dolphy. Tenor saxophonist Clifford Jordan is no Coltrane imitator, but he plays with a hard-edged fire. And if Miles Davis’s rhythm section in 1964 (the one animated by a 17-year-old Tony Williams and Herbie Hancock on piano) was being hailed as revolutionary for spontaneously altering tempo as a collectively improvising ensemble, well, pianist Jaki Byard, drummer Dannie Richmond, and Mingus move from swinging four-four to shuffled waltz time and back again quite fluidly. And those ensemble accompaniments behind Dolphy as he solos: they are crazy-ass and dissonant. It’s the whole band taking liberties, not just the soon-to-be-leaving Dolphy.

This band’s version of “Faubus” is more than a half-hour long, and it abounds with wit and wild freedom, with each player essentially being given the steering wheel with total latitude. Byard plays some solo piano where he integrates “Yankee Doodle Dandy” with “My Country Tis of Thee” amidst stride and blues playing. (Political commentary indeed.) Mingus suggests the level of the governor’s intellect by playing with a child’s lullaby during his section. And Dolphy’s brilliant bass clarinet solo draws the entire band into a manic improvised ensemble section that sounds rehearsed by the time it climaxes. For all that, the written ensemble portions of the track are swinging and ragged at once, precise and pleasantly frayed for enjoyment.

Mingus was hardly without a potent connection to jazz tradition in 1964, however. Byard plays a delirious, stride-y, delightful piano solo to introduce a piano-and-bass-only reading of Ellington’s “Sophisticated Lady”—with Mingus playing as melodically and full-toned as possible. No 1964 audience member wanting “jazz” could have possibly asked for more. Then “Parkeriana” leaps out with the whole band paying tribute to Charlie Parker. Sure, the stop-and-go nature of this patchwork of themes suggests some of the new jazz that would emerge 40 years later, but each piece is swinging and familiar. And joyous.

The 1975 band is smaller but just as potent: a quintet with Don Pullen on piano, trumpeter Jack Walrath, George Adams on tenor saxophone, and Richmond and Mingus. Their “Faubus” is a more crisp and antic, with the ensemble taken at a clip, Pullen splattering more expressively on the piano, and Richmond integrating a bit of R&B backbeat into the theme’s glorious stop-time sections. While everyone gets a solo here, the sections are shorter and proceed more within a single tempo and feeling. On this basis, then, it might be no surprise that the 1975 audience was more enthusiastic: the 1975 band is tighter and, in one sense, at least, more traditional.

Sort of. Much of the music in 1975 was new material from the recently released Changes One, one of the bassist’s finest recordings, and certainly a jewel of the later years. Ironically, a good swath of this material is gorgeous and lush, beautiful, hardly more difficult, or more “modern”. The version of “Duke Ellington’s Sound of Love” (a Mingus original that builds on Ellingtonian chord changes) features exceptionally lyrical solos from Adams and Pullen, both of whom should be remembered for combining both lyricism and freedom. “Remember Rockefeller at Attica” is also from Changes One, and it is a bright swinger that features a lead-off solo by Walrath that is superb: clear, expressive, virtuosic in the mode of Freddie Hubbard.

This quintet show off on track after track is how utterly they had integrated the freedoms Mingus was figuring out in 1964 with the leading edge of what would become a neo-traditionalism movement by 1982 or so. Walrath, Adams, and Pullen can play any style of jazz with tonal clarity and technical precision while expressing themselves personally—they aren’t exactly the “young lion” generation that would appear with Wynton Marsalis and his peers in another decade, but they have all of those skills in hand.

So, for example, on another Changes original called “Sue’s Changes”, they move nimbly through different tempos and each articulate solo cadenzas of sonic dazzle. Walrath reminds you that he is one of the most underrated trumpet players of the last 50 years, and Adams plays something that shows the melodic command of Sonny Rollins, the tonal brilliance of Michael Brecker, and the post-modern blues feeling of David Murray. Pullen’s piano solo covers what would seem to be the entire history of the instrument, climaxing in a section in which his fists are rolling over the keys in an expressive joy that is singular to this great artist.

Just as the 1964 Bremen concert featured a simple blues, the 1975 concert gives the crowd “For Harry Carney”, which is a grooving kind-of habanera around a modified 12-bar structure. It is both a meat-and-potatoes classic and forward-thinking. And the 1975 concert ends with another gut-bucket track—”Devil Blues”, which features a raw vocal by Adams that takes you way back while drawing you way ahead as well.

It is difficult to reconcile the exceptional sound and technique of Mingus’s 1975 bass playing in Bremen with the fact that he was suffering from amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and would soon be unable to play his instrument at all, dying at the age of 56 only four years later. It is not just the band that sounds all-time superb here but also the leader as a player. His intonation and imagination are equally sharp, with a huge, driving tone. He was only 53 years old and at the height of his powers.

Listening to both of these concerts in sequence, of course, you are put on notice that “the height of his powers” lasted at least 11 years. And given that Blues & Roots and Mingus Ah Um are from 1959, we have to back up “the height of his powers” at least another five years. Add another six to that if you want to go back to that Massey Hall concert in 1953. I certainly want to, meaning that Mingus was on the jazz mountaintop for at least 22 years. That is an astonishing length of greatness.