Posted: by The Alt Editing Staff

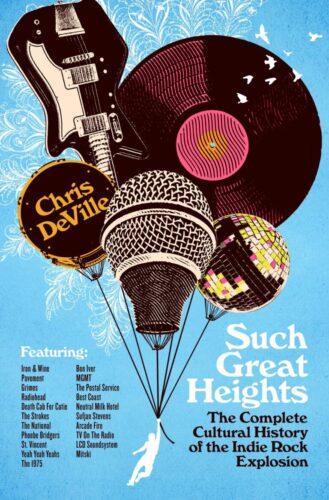

The Alt’s Bookshelf is a series where our staff highlights some of their favorite books and zines related to music. In this installment, Zac reviews Such Great Heights: The Complete Cultural History of the Indie Rock Explosion, the new book by Stereogum editor Chris DeVille.

In his new book Such Great Heights: The Complete Cultural History of the Indie Rock Explosion, Stereogum editor Chris DeVille takes on a nearly insurmountable task: summing up the past twenty-five years of indie rock in about 300 pages. The genesis of the book, as he told The Pitch, was that he “started thinking about my lifetime of experience, and I felt like indie rock had a history that hadn’t been sufficiently articulated, especially in how it morphed into pop music over a couple of decades.” In other words, he wants to explore the way “’indie’ music [went] from Pavement to Carly Rae” (293), he puts it later on. This is the narrative thread DeVille chases throughout Such Great Heights, the way indie shifted from the periphery of culture to its center and the causes and knock-on effects of that change.

As such, DeVille himself isn’t much of a character in Such Great Heights; instead, he’s something of a reader avatar, the archetypal indie rock fan. He begins with a brief overview of his relationship with the genre in his teen years, and notes that the appeal of the music “wasn’t about DIY ethics, avant-garde disruption, or any kind of radical worldview” for him at the time, the draw instead being “albums I could spin incessantly and organize into lists in place of a personality, songs I could burn onto mix CDs for my friends and family to show off my good taste, and bands that doubled as a secret handshake with people cooler than me” (21).

In DeVille’s own words, he was at the time just “someone with average-or-worse charisma, looks, and athletic ability, who’d never had much to brag about besides my grades, [so] I bought into the snobbery that often seemed inextricable from indie-rock fandom” (21). Honestly, whom among us? This story is certainly the one bound up with the genre in popular consciousness, so he’s a fitting guide through the evolution of the genre. That said, again, DeVille mostly sticks to recounting events and tying together disparate trends; Such Great Heights is about indie rock’s journey through the 2000s, not DeVille’s journey through indie rock. While he includes here and there anecdotes of his own life that relate to the points being made, we as readers don’t follow him as he discovers this band or that, really.

Nonethless, DeVille writes in an engaging and personable enough style that it never feels like he’s merely reciting history. He’s knowledgeable, but what comes through more is his passion; it’s clear that this book is from a deep love for this style of music and the culture that’s formed around it—even if he might fairly critique certain aspects of it. DeVille isn’t blinkered in his view of indie culture, and he takes to task the sexism and racism present in much of the community; his reading of the genre’s embrace of pop music, too, is more generous and less cynical than others might be.

As he tells it, there is no one factor that brought indie rock to its current state; rather, various processes, stakeholders, and technologies, and cultural ‘vibe shifts’ played into the change. In particular, he names “Hollywood’s embrace of indie music post-The O.C., the star-making pipeline of Pitchfork and blogs, an explosion of indie dance music, the commodification of thrift-store fashion and twee sensibilities, [and] the horizon-broadening impact of MySpace and iTunes” (181) as some such causes. He spends time on each, although not necessarily in order and not all to the same degree. Each chapter roughly corresponds to a different factor behind the shift; DeVille spends a considerable amount of chapter three discussing the way that movies and television shaped popular conceptions of indie music in the 2000s, for example, with The O.C. and Garden State serving as the paradigmatic indie TV show and movie, respectively.

For readers looking for the simplest answer, Such Great Heights offers that indie rock fans just got sick of indie rock. “When that music got a mainstream foothold and it became clear there was an audience for it, money flowed in, and the baseline understanding of indie was reshaped in our image. Hipster became a lifestyle brand, which in turn was gentrified into the baseline of millennial yuppie culture, soundtracked by a defanged version of indie rock” (294) that sucked out everything that made the genre special to its fans in the first place. When indie became a brand, it lost its appeal. “When normies adopted ‘Mass Indie’ culture as their own, it led to the proliferation of hazy IPAs and the Grammy-friendly version of indie rock that ultimately yielded Mumford & Sons. Hipsters who defined themselves as different and cutting-edge rushed away from all that” (294), and when the underground is no longer underground, where else is there to go? Indie rock had won, Deville writes, and “with Arcade Fire winning Grammys, Best Coast invading Urban Outfitters, and a slew of indie imitators on the pop charts, the genre no longer seemed cutting-edge” (252).

This feeling of betrayal ultimately led to fans “noticing how much Fleet Foxes had in common with the Lumineers and thinking, ‘Ew’”(295). Such fans had already been primed to move past guitar-based music after years of contact with synth-pop, dance-punk, and hipster-approved electronica; The Postal Service, argues DeVille, was patient zero for indie’s gradual shift, and likely because of their wholly unexpected success. “Give Up quickly surpassed Sub Pop’s estimate of 20,000 in sales” and the duo’s LA show was moved “from 130-capacity DIY space The Smell to the Palace Theater, a venue ten times that size” (42). That band opened doors previously blocked off for indie artists, allowing electronic elements to be treated as commonplace rather than as blatant overtures to the mainstream, even as they did end up accruing that semi-mainstream status: “Give Up kept growing. Eventually it went Platinum and became the second best-selling album in Sub Pop history behind Nirvana’s Bleach. But the record hadn’t only been a hit for the Postal Service—it opened up a whole new lane within indie music. Soon that lane would be populated by arty eccentrics like the Knife and of Montreal, dreamy nostalgists like M83, and clubby synth bands like Hot Chip and Cut Copy. By the time the ultra-hooky world-conquerors Passion Pit and MGMT came along in 2008, indie synth-pop bands were normal, not novel” (43). The arrival of LCD Soundsystem onto the NYC indie scene played a large role, too, and his name-dropping of Daft Punk helped legitimize their Discovery as an essential stepping stone from indie rock to electronic music (with Justice’s Crosses a scrappier companion piece). This was, in DeVille’s words, “electronic music that felt specially catered to a rock audience” (145), so that when electronic music for electronic audiences began gaining purchase, it wasn’t too much of a leap.

The alternative, after all, around the same time was “a bizarre Sufjan Stevens aftershock” in the form of the “wave of radio-friendly artists that emerged in the early 2010s to make stomp-clap folk rock wildly popular” (198). By this time, with hipsters fully bought into mainstream stars like Kanye West (famously earning the 2010s’ only perfect Pitchfork score), Robyn, and Frank Ocean, it was only a matter of time before the opposite began to happen: indie rockers turning genuine superstars. We know that the one person who truly “understood how to move through the space where the underground and the mainstream intersected, and he rapidly claimed it as his own” (318) was Jack Antonoff, who more than any other figure shaped the sound of mainstream music in the 2010s; his work on Taylor Swift’s 1989 seems, in retrospect, to be the genuine jumping-off point for indie’s imperial era, which arguably culminated with Swift’s two quarantine albums. Swapping Antonoff out for members of The National, Swift pivoted to “the softened Hollywood version of ‘indie’ that emerged after The O.C.” (293) on folklore and evermore, recruiting West collaborator and Grammy winner Bon Iver for the title track of the latter.

Swift would, of course, tap indie darling Phoebe Bridgers to open a leg of The Eras Tour in 2023, after Bridgers had already thoroughly infiltrated the mainstream, having been nominated for four Grammys, infamously appeared on SNL, and guested on Red (Taylor’s Version). DeVille, admittedly, spends a bit less time discussing the newest wave of indie mainstays than he does on figures from the previous decade and a half or so. One could quibble that DeVille should’ve spent more time discussing, say, Foo Fighters tourmate Alex G or Lil Yachty’s bestie Faye Webster, but to do so would miss the forest for the trees. In Such Great Heights he traces a history—it’s right there in the subtitle. By the time artists like Bridgers or Mitski—perhaps the biggest indie rocker in the world today—had ascended to the upper echelons of the genre, crossing the now-porous border between indie stardom and actual stardom, the main narrative of Such Great Heights has more or less come to a close. For all intents and purposes, indie had already become mainstream; that’s the only way these artists could break containment.

The most interesting thing that DeVille does throughout the book is dive into the material factors behind the shift. He examines artists foundational to the blending of styles, discusses the way visual media contributed to shifting perceptions of indie, but in the era of the right-wing Gramscian, everyone’s looking for a tangible explanation, and it’s in his discussion of the nature of new technologies that Such Great Heights is at its most illuminating. Social media, for example, and particularly MySpace, played a huge role in both getting bands out into the world and deepening the personal connections listeners felt with their favorite artists in a sort of proto-parasocial manner. He takes a brief detour when discussing MySpace to briefly trace the path that emo took during the 2000s, noting the similarity of its rise and commercialization to indie rock’s own. From there, though, he discusses the way MySpace was a launching pad for indie darlings like Arctic Monkeys: “the historic association between the band and the social network was so strong that in 2019, the NME called Arctic Monkeys ‘undoubtedly MySpace’s biggest success story’” (124). For a more thorough history of the relationship between MySpace and underground music, he directs readers to Michael Tedder’s Top Eight.

When he digs into the way that the MP3 era contributed to the genre’s evolution, the tone of Such Great Heights changes rather subtly. He does celebrate the way that changing technologies encouraged omnivorous listening habits, suggesting that prior to the development of MP3 players, “music fans had closely defined themselves by their favorite genre—punk rockers, hip hop heads, and so forth—but in the MP3 era,” where nearly any piece of recorded music was available on LimeWire or Napster, that self-identification was a choice rather than a necessity, and “eclecticism was the wave” (105). In analyzing Apple’s role, DeVille focuses just as much on the company’s branding as he does their products. The iTunes Store model worked to highlight artists who might otherwise fly under the radar, but it was their ads that helped truly break many indie artists. As the company attempted to paint itself as vital, cutting-edge, and above all else cool, they turned to (relatively) underground artists to convey that message. Apple’s placement of songs by CSS and Gorillaz, he argues, essentially broke both overnight.

Similarly to Liz Pelly’s concept of streambait pop, although less derisively, DeVille also notes that with the rise of streaming services and especially Spotify listeners began gravitating towards less challenging and more accessible artists. These were those who fit the profile of that post-The O.C. style of indie rock, soft and pleasant music like Mac DeMarco’s, to use an example given in Such Great Heights. While he doesn’t denigrate such artists, it’s clear that DeVille has no love for the streaming industry; his posture throughout the book, indeed, is one of overt skepticism toward cynical operators, as he views them, who turned his beloved music into another product, the “corporate overlords [who] tried to capitalize on the now-ascendant indie scene. Indie rock was no longer just a genre; it was a lifestyle to be sold, a demographic to pander to, a craze to cash in on” (64). This attitude, as he acknowledges throughout Such Great Heights, was once the lifeblood of indie music. Indeed, this ethos was the genre’s raison d’etre. While he goes out of his way to point to the material reasons that caused, for example, Grizzly Bear to license their music for commercials, taking pains to make it clear he does not begrudge them their attempts to make a living off their music, he also laments the way that the genre’s adversarial posture against entrenched institutions has faded into the background. He blames not the artists themselves but the puppet masters behind the scenes, keeping with indie’s original anti-corporate ethos. In his own way, DeVille attempts to revive that strain of indie culture throughout Such Great Heights. Whatever else might have changed since 1999, he hasn’t lost his edge yet.

Such Great Heights is out now.

––

Zac Djamoos | @gr8whitebison

The Alternative is ad-free and 100% supported by our readers. If you’d like to help us produce more content and promote more great new music, please consider donating to our Patreon page, which also allows you to receive sweet perks like free albums and The Alternative merch. And if you want The Alternative delivered straight to your inbox every month, sign up for our free newsletter. Either way, thanks for reading!