Frank Zappa was many things: a counter-cultural icon of the 1960s, a shredding guitar virtuoso, a creator of bracingly cynical and satirical rock music, a composer of orchestral music, and a political pundit and activist. Alex Winter’s new documentary, titled Zappa, portrays all these facets of the man’s personality and reveals the personal journey of a complex man, sometimes aloof, but always single-mindedly dedicated to his work.

Zappa was prolific: touring relentlessly and releasing over 60 albums of music during his lifetime, with many more released posthumously. To tell a story this sprawling, documentary-maker Winter sought the cooperation of Zappa’s family, who held the key to the vast archive of audiovisual material Zappa had collected himself during his long and varied career. Winter himself became famous as one half of iconic movie duo Bill and Ted, directed the cult movie Freaked (1993), and more recently has directed accomplished documentaries such as Deep Web: The Untold Story of Bitcoin and the Silk Road (2015), The Panama Papers (2018), and Showbiz Kids (2020).

In his discussion with PopMatters, Winter reveals how he managed to get such access to the rare footage archives of his hero, why he focused more on Zappa’s “emotional life” than his studio sessions, and what were his perfect entry points into one of the wildest discographies on the planet.

I’ve always loved the story, which you recount in the documentary, of Zappa as a boy going out and buying a recording of the composer Edgard Varèse, just because he’d heard it was “noisy” and had lots of percussion on it. This whole world of experimental music being opened to him as a result. Is there an “origin story” behind how you got into Zappa?

It’s not quite as clean as that. I think that the equivalent is that I was a kid growing up in St. Louis, sitting in the living room of my best friend’s house when Zappa came on Saturday Night Live, and being captivated by his persona. He didn’t seem like other rock guitar players of that era: he was funny, he was acerbic, he was political. His music had a strange quality that didn’t seem to fit within the niche of rock. But it took me many years to “get” Zappa, to find a way into all the music as opposed to just an album here or there.

How did you go about pitching the documentary to the Zappa family?

I had a particular way in. I knew that I wanted to tell a story that was as much about a man and his times as it was about a musical artist. I wanted to try to get at something intimate, personal, and human. Especially as he was an artist that many people found difficult to access. I knew there was a human being there, so I thought: let’s access the human being, let’s tell that story. His life was so fascinating that I knew that the biographical elements on their own would be fascinating. That’s really what I pitched to Gail [Zappa’s widow]: a more intimate examination of an artist living in a particular time and the decision to live that sort of life, and what sort of consequences Zappa had to face by living by that kind of artist’s code. She thought that was very compelling. She and I became quite friendly, and she opened the vault up. That’s what gave us the ability to tell a more intimate story.

Image by Pete Linforth from Pixabay

Image by Pete Linforth from Pixabay

Once you had the green light on the documentary and on using the vault, how did you start putting the film together? Did you start with the story you wanted to tell and then look for footage? Or did you start with the footage that you found?

It’s always been both at once, and often at odds! Either the story you want to tell is at odds with the media you’re getting, or the media you’re getting is at odds with the story you want to tell. In this case, it was like that times 1,000 because we had so much media. I wrote out a very specific narrative, which I knew we would change or maybe even get rid of. It’s always a blueprint with a documentary; you can’t be rigid about that. Mike Nichols [the film’s editor] and I just started immersing ourselves in the media. What helped us immensely (we didn’t even know it existed) was hours and hours of first-person footage from Zappa himself. Video, film, and audio that he’d captured of himself down in the basement, just shooting the breeze with friends, political pundits, and journalists who came by the house. There were miles of it! So we built a timeline in Zappa’s own words that was a foundational bed for us. It gave us a way into his thinking, and that was our code for building the narrative.

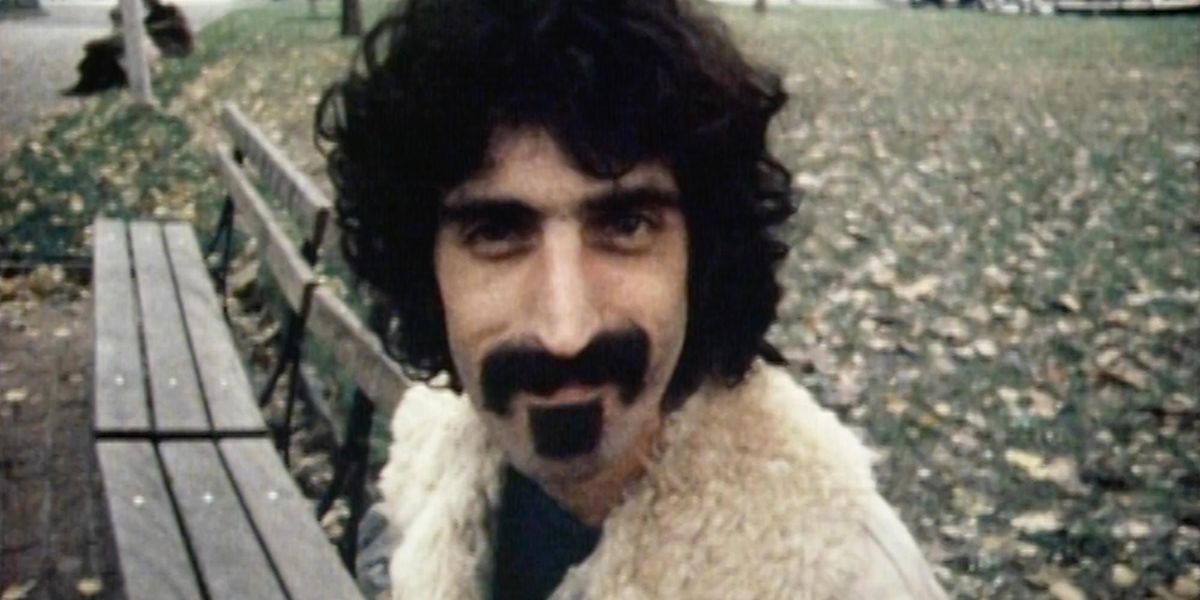

Photo: Roelof Kiers / Courtesy of Magnolia Pictures

To clarify, by “first-person”, you mean Zappa himself is the camera operator?

In almost all the archival, Zappa’s not in it because he’s shooting it, which is crazy! I mean, you’re dealing with a guy whose first artistic love was film, filming everything around him and editing it himself, starting from when he was very young. Later he had his own Beta camera and would walk around the house, recording.

Could you talk a little bit about the work you had to do to convert the stuff in the vault to a form so that you could use it?

That’s a very long story. The shortest version I can muster is that Gail wanted us to use the vault material. But it was far bigger than I’d anticipated, by order of magnitude, and a lot of the media was very old and in disrepair. As you know, video is very brittle, especially old reel to reel and 1″ and 2″ video. The audio tracks for film are extremely fragile. I took one look at this vault and thought, there are two years of my life that I’m going to have to spend right there! The Kickstarter campaign to preserve it took over two years, and that was before the doc was financed at all. During that period, we were screening the media and moving it onto both archival digital tape and regular media drives that we could use to edit with. It was an exhaustive process.

Was there anything you regretted not being able to include in the film?

Honestly, not really. We were really happy with the film. It’s kind of like pulling a thread on a sweater: the more you pull, the more it unravels. We really wanted to tell a concise story that focused on Zappa’s emotional life. We felt that the more anecdotal, fun, fan service type stuff that we jammed in there, the more diluted and disorienting the film would become.

Zappa’s lyrics were always intended to be provocative, but I can’t help but see some of them (the bawdy focus on sex with groupies, for example) a bit differently these days, and they would certainly land differently in today’s media landscape. Did you feel like you had to represent that side of Zappa in a particular way?

I was very interested in digging into that side of Zappa. I told Gail that I wanted to do that the very first time we spoke. To get a nuanced portrait, we had to be able to discuss the more problematic aspects of his personality. They speak to the better aspects of his personality. It’s all part of one portrait. It was very important to me to dig into that, and I was grateful that Gail was amenable and would speak to me about the difficulty of living with someone like that. There was no point at which I wasn’t going to cover that. It really wouldn’t be a comprehensive portrait if we hadn’t been able to discuss it all.

Photo: Cal Schenkel / Courtesy of Magnolia Pictures

I was really happy to see the animator Bruce Bickford featured prominently in your film. He was one of many incredibly talented people who collaborated with Zappa. Who was the Zappa collaborator you most wanted to talk to, and what did want to you learn from them?

I really wanted to meet Bruce! I’d been aware of him since he provided the animation for Zappa’s concert film Baby Snakes. I was a huge fan. I went to film school and was inspired by animation at that time. People like Bruce, people like Norman McLaren, Jan Švankmajer, and the Brothers Quay. That whole world of experimental animators is my thing!

I met Bruce quite a few years ago and was able to go up to his studio in Seattle and film there. We were lucky because he passed away not long after that. He was an amazing human being. I found an enormous amount of archival that he’d made for Zappa that he hadn’t seen himself since he filmed it.

Ruth Underwood [the percussionist who was a member of Zappa’s band for much of the 1970s] was also someone I’d always been extremely inspired by. Pretty much everyone I spoke to was helpful, and that includes people I spoke to who aren’t in the film. Zappa was connected to so many phenomenal artists. I talked to Eric Bogosian and “Weird Al” Yankovic, who was very inspired by Zappa.

The documentary ends with a complex mix of strong emotions. On the one hand, there’s a feeling of heroic failure, and yet there’s also a sense of hope in the form of Zappa’s advocacy on behalf of the new democracies of Eastern Europe. I’m curious to get your perspective on how you approached the ending.

To me, the ending is not exactly ambiguous, but it’s multi-faceted. I tend to feel that the end of one’s life is rarely this perfect summation, either for good or ill. It’s rarely reaching this apex of triumph or utter tragedy. I feel the same about Zappa’s life. It was neither all good nor all bad. There was an enormous sense of triumph: he’d finally inspired all these young musicians who’d come up and who were interested in playing his orchestral music properly, which he’d never heard done, and which I think was extremely satisfying for him.

At the same time, his life was cut drastically short. He was very creatively powerful at the time of his death, and he was not waning in any way, shape, or form. He had all sorts of projects that he wanted to do after The Yellow Shark [the aforementioned concerts and resulting album of orchestral music], and that’s obviously quite tragic. The ending is all of that wrapped up in one. Your life ends when your life ends. People don’t often get to decide when that is. It’s often not on your terms. But I think that it was a very grand gesture, that concert.

I don’t get any sense of ingratitude from him; he was extremely moved by those recordings. There’s a lot to unpack, which is why the ending can feel a little emotionally overwhelming. I like that. I think that’s true to where he was at the end of his life.