I’m always intrigued when I see two authors listed on a graphic memoir. I know what that usually means for a graphic novel: the first name is the writer, the second the artist. But both Vivian Chong and Georgia Webber are artists. For monthly comic books, that usually means the first name is the penciler, the second the inker. But again, not this time.

Chong’s and Webber’s individual art sometimes occupies separate pages, sometimes separate panels on the same pages, and sometimes separate elements within shared panels. The combination is an interwoven visual conversation, based in part on actual face-to-face conversations they had at Chong’s kitchen table (as drawn by Webber). It also merges—and in some cases literally tapes together—artwork spanning more than a dozen years.

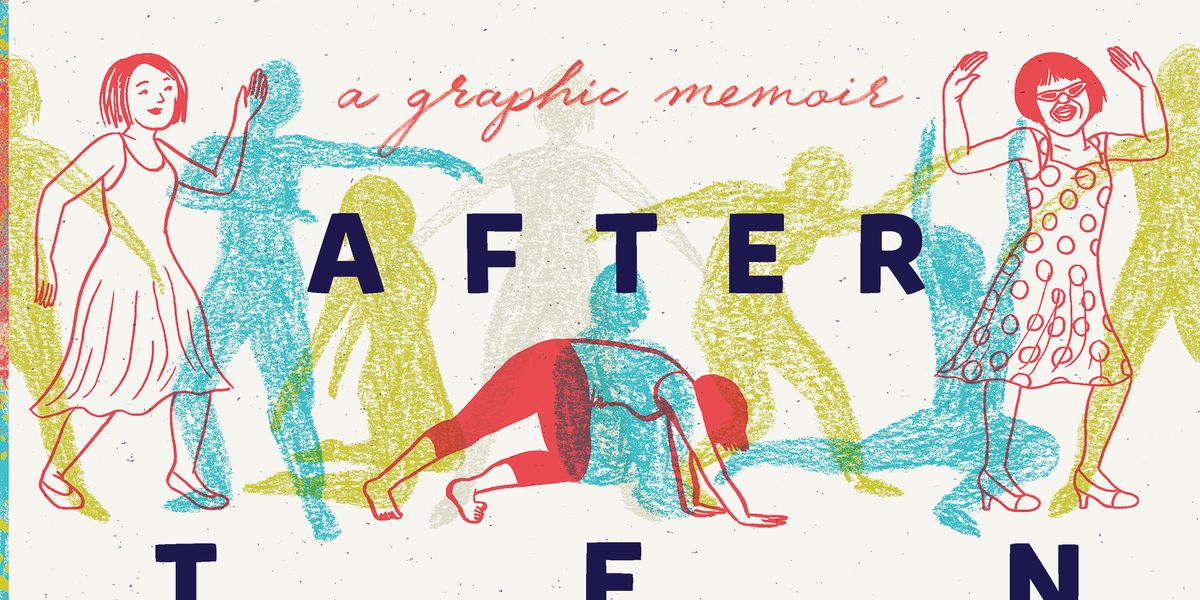

Chong, who is now blind, briefly regained a portion of her vision and immediately began drawing a memoir of how she lost her sight to a rare syndrome (toxic epidermal necrolysis, the “TEN” of the title). Her regained sight only lasted a few weeks before the syndrome left her permanently blind, but she sketched dozens of images first, all in a frenetic sometimes scribbled style as her eyes worsened and she leaned her face closer and closer to the paper.

She abandoned the project, but kept the pages and eventually shared them with Webber (via choreographer, Kathleen Rea. See the resulting Dancing with the Universe video, below). Webber once suffered a severe vocal injury, and Fantagraphics published her memoir, Dumb: Living Without a Voice, in 2018. She and Chong worked together, arranging and filling-in and further widening Chong’s initial artwork. The result is one of the most fascinating collaborations in the comics form I’ve seen.

I’m always interested in process and how a finished product encodes the history of its making, and that’s wonderfully evident than in Dancing After TEN. Where the sudden shifts in style (Webber’s lines are thick, clean, and flowing—essentially the opposite of Chong’s thin, choppy ones) might feel disruptive in another work, they always gesture to not only the creative process (Chong and Webber seated together working) but the parallel disruptions in Chong’s actual experiences. The surface of Chong’s drawings tell the story of her losing her vision (her ex-boyfriend’s sister lied and gave a her pill that triggered the syndrome while they were on vacation), while their hectic execution evokes the much later story of her briefly regained vision.

The combinations are also artful in themselves. Webber’s lettering and speech containers appear within Chong’s drawings, and Chong’s drawings often provide backgrounds for Webber’s art. The two artists also chose a fitting two-color approach: each page combines a range of black and blue gradations, further unifying the memoir. Later pages also give space to each artist individually. Webber abandons the two-row panels that dominate the memoir for an open arrangement of more detailed figures and settings. The stylistic change parallels and so helps to express Chong’s psychological change as she embraces her new life. That includes taking up the pen again.

The final pages feature Chong’s new art, drawn with Webber’s encouragement. As Chong explains in an ending note: “TEN did not take away my ability draw, just my ability to see my drawings.” Some of the images abstract, a spray of lines evoking emotions. Others are representations of herself, sometimes with her seeing-eye-dog, sometimes of her dancing alone. Her contour lines evoke shapes, movement, and through their misalignments, the challenges of and her energetic responses to living without sight.

As much as I admire the combined artwork, I suspect most readers will be most engaged by Chong’s story—not just the struggle and bravery of overcoming hardship, but her skill in shaping events and the extraordinary details of the plot. The opening chapters leap between distant moments: leaving from the airport for the eye surgery, arriving in St. Martin for the fateful vacation, deftly making tea for Webber in her apartment, waking from an induced coma. Wong weaves the fragments into emerging coherence that reverses the trajectory of her trauma within the story.

She also depicts two of the biggest asshole boyfriends I’ve ever seen in a graphic memoir. Her portrayals are forgiving—literally when she declares her forgiveness to the one who abandoned her in the hospital and lied to their friends about where she was. The other one asks her to “watch” his bag at the terminal, complains that there’s no TV in her hospital room, leaves instead of taking notes for her while she’s consulting with doctors, and hints that he doesn’t want to wait there if the surgery is going to be long. I forget which one started sleeping with someone else while she lingered unconscious for two months. The grueling tale of her physical recovery parallels the psychological recovery from dating such horrible human beings.

The last third of the memoir loses some plot focus as a result. There are still fascinating details (Chong learns yoga, becomes a stand-up comic, overcomes her fear of dogs, loses her hearing), but the narrative shape is less satisfying—until the last portion draws in the memoir’s sweeping energy again. Dancing at TEN documents both an extraordinary life story and an extraordinary creative process that crowns it.

Now I want tickets to Dancing with the Universe, the resulting play that includes Chong dancing and performing as herself.

“Dancing With The Univer”Dancing With The Universe” April 9 to 18, 2020 at the Betty Oliphant Theatre in Toronto