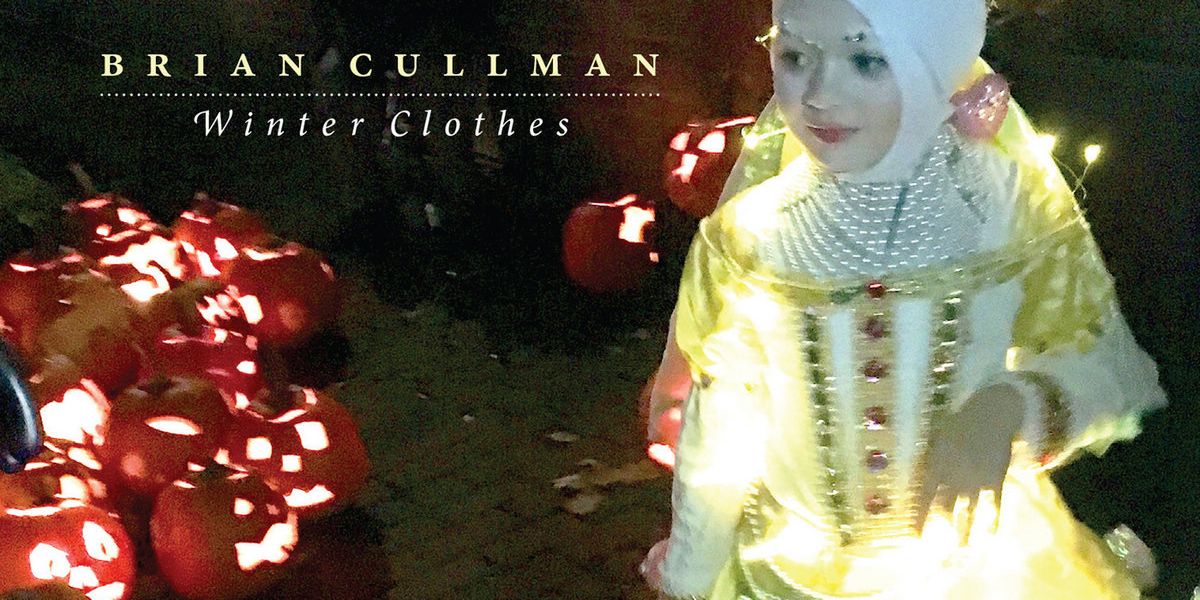

Winter Clothes is the new new release from writer/musician Brian Cullman. Out 11 September via Sunnyside Records, the LP is a deep collaboration between Cullman and his late friend Jimi Zhivago (Glen Hansard, Ollabelle). Zhivago passed in late 2018, just as the initial sessions for the record were winding down.

Cullman eventually returned to complete the record, which features a wide range of collaborators, including Byron Isaacs (The Lumineers, Ollabelle) on bass, backing vocals, and occasional drums; and Glenn Patscha (Ry Cooder, Ollabelle) on keyboards and backing vocals. Later sessions filled out the sound, adding Chris Bruce (Me’shell Ndegeocello, T Bone Burnett) on guitars; Christopher Heinz on drums; Tony Leone (Chris Robinson Brotherhood) on percussion; and Syd Straw (The Golden Palominos) and Maryasque Fendley (Basque) on backing vocals.

The album is sometimes celebratory, sometimes sad, and filled with a life-affirming quality that further establishes Cullman as a formidable songwriting talent. Songs such as “Killing the Dead” and “Wrong Birthday” accentuate his powers as a lyricist, while the group of players he assembled help make the collection one that appeals to both casual listeners and those who engage with the music on a deeper level.

Cullman, who has previously collaborated with Robert Quine and Vernon Reid has also contributed award-winning journalism to publications such as Creem, Crawdaddy, Musician, Rolling Stone, Spin, Details, and The Paris Review. He spoke with PopMatters from his home in New York about making the record and his friendship with Jimi Zhivago.

Where did this record begin for you?

It was a real collaboration with Jimi Zhivago. He was a really, really dear friend. He was an original member of the band Ollabelle. They’re one of the great lost bands. Live, they were just sensational. They’re all really polite. They’re very Canadian in that way. He was sort of the wild card in that band. Jimi was about 20 years older than everybody else in the band. He was sort of the fuckup. He could never remember what key a song was in. He could never remember chord changes, but he had a spark. When he’d find his way into a song, he’d make it really come alive. On stage, when he was with them, it was really, really powerful. He’d stumble, go off in the wrong direction. But when he found his footing, he would just take the band somewhere they didn’t imagine going. It was really sensational.

They kicked him out. About two years into the band. Really, for being a fuckup. He was drinking too much, doing a lot of naughty stuff. They kicked him out but stayed friends with him. They stayed in touch. He went into his own version of recovery, got sober. Unlike a lot of other people I know who have come out on the other side, he got really happy. He got really positive. He just put all of his energy into playing. His playing got so much better.

He was my partner in everything musical for the past five years. This record was one that we really did together. I wrote the songs, but then we’d go in the studio, usually just the two of us, maybe with a bass player, Byron Isaacs [Ollabelle, the Lumineers], or Glenn Patscha[Ollabelle]. I’d start playing chords, and Jimi would start playing alternate chords with me, and it would turn into something usually very different than I expected. He was a big part of the whole process.

Right.

I’m leading up to the bad news, which is that in the middle of recording the last song for the record, which turned out to be the first song on the record, “Killing the Dead”, he was feeling really poorly, and he went to the hospital and never came out.

Oh no.

He was given the wrong medication for his condition. It shut down his liver. It was heartbreaking. I had to step back from the record for almost a year before I could think about it again, and then I finished it up with Glenn and Byron and a couple of other friends. In a lot of ways, this is Jimi’s record as much as mine. He gave me so much, both in terms of his encouragement and in terms of his musicality. I just wish I could have worked on a record for him because he deserved his own album. Let’s call this a co-album, one we did together.

Is there something you can point to on the album that you feel really captures his spirit, his musicality?

It’s pretty much everywhere, but there are a couple of songs where he just let loose. I think the first one we recorded is really silly, a throwaway track, but I love it. It feels to me like a Stones’ outtake. That’s “Wrong Birthday”. He just cranked it up, played a Brian Jones part, and then, at the end, started acting like he was both in the band and the audience. He started clapping and going, “E-oooo!”

He had so much fun with that. There’s another track where it was really the two of us just sitting together. That’s called “Someday Miss You.” It’s sort of refracted blues. We recorded it live with the two of us playing acoustic guitars, Jimi playing slide guitar and Byron playing standup bass. There are some little time problems. We go in and out of sync, but it’s so loose, and it feels so natural. It’s a lovely recording. That’s Jimi’s spirit. He really was at his best when he didn’t know where he was going.

There’s a spontaneity throughout the record. Was a lot of it tracked live?

Almost everything was. The original tracks were live, and then after Jimi passed, I went in and cleaned up the record with Byron and Glenn and a guitarist named Chris Bruce [Me’shell Ndegeocello, T Bone Burnett] who came and filled in a lot of the parts that Jimi would have put on. Chris is something of an unsung hero on this project. One of his real strengths is playing stuff you can’t hear, but you can feel. He would put these little things on, and I’d say, “What the hell is he doing? I can’t hear anything.” But the track would sit differently. He had that knack for framing things and making everyone else sound good.

There are certain actors that can do that. They’re so generous with their time, and with their energy that everyone else on the screen looks great, and then you come back to it, you realize, “It’s that actor, they made everyone else look good and look comfortable.”

You mention that it took you a while to come back to the record. What was the turning point?

None of us need time; we need a deadline. My record label, who are really lovely people and really kind to me, said, “You know that record you were going to give us about nine months ago? Could we get it in three weeks?” I only really needed about two days in the studio to add some parts. Hector Castillo needed about five days to mix it.

There are a few mentions of parties, festive moments on the record. But they don’t always play out the way we expect them to. Were you in a particular mindset when you were writing the lyrics, or were you thinking about specific things that would unify the lyrics?

No, not at all. But one of the things that made me so happy was this: Songs seem like they’re really ephemeral, and they seem like they’re so harmless. Whenever someone gets really excited about a song or really offended by a song that I’ve written, it’s sort of a thrill. There’s a wonderful singer I work with, Jenni Muldaur. She’s an amazing vocalist. She came in to do a harmony with me on the song “New Year’s Eve”.

It’s a silly song, but I thought, “Wouldn’t it be great to have a perennial?” Just a song that would be my version of “White Christmas”. I gave her the lyric sheet, she went in to start singing, and halfway through she stormed out and said, “I’m not going to sing this! The guy singing this is an asshole! ‘You can call me a cab, but I’m not going to leave’? I know too many people like that!”

Part of me was really upset because I love her voice and really love her singing with me. The other part of me was, like, “Damn! This got to you! I’m thrilled.” I was really flattered.