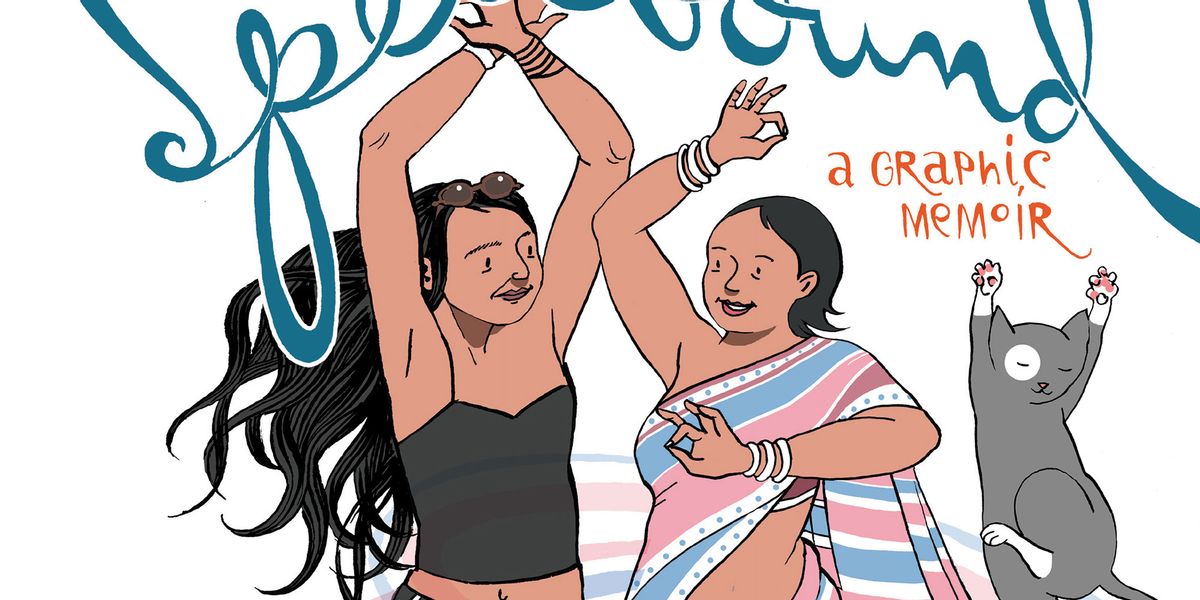

Bishakh Som’s graphic memoir, Spellbound, is an innovative and captivating tale, an attractively drawn and brightly hued memoir which disguises some big ideas beneath its seemingly prosaic surface.

Spellbound’s magic is its subtle beauty; its endearing framing of the everyday. There’s not a whole lot that actually happens throughout the comic, which follows roughly a year in its protagonist’s life after she quits her well-paying but stultifying job as an architect to pursue a more precarious livelihood as a comics artist. Indeed, delivered mostly in easily digestible two-page chapters, the reader is at first startled by the relative lack of action.

But it is this very quality – the deliberately slow and realistic pace of the narrative – that proves ultimately rewarding, giving an authenticity to the narrative that is more compelling than the sped-up storylines of faster-paced tales. Readers can relate to the protagonists, who struggle daily with their sense of professional inadequacy; their yearning for something – anything – interesting to happen; their unmet desires to love and be loved.

Fire by google104 (Pixabay License / Pixabay)

The story is evocative of Nick Drnaso’s 2018 hit Sabrina, but it improves upon the many shortcomings of that over-hyped work. Where Sabrina was presented almost exclusively through the white male gaze, and was populated by misogynistic, self-absorbed white men, Spellbound is jam-packed with queer folk, multiracial diversity, and interesting women and trans characters. It shares with Sabrina a similar sense of pacing – that slow, idle progression through daily ennui and anti-climax – but its diversity renders it less dull, more authentic, and full of life. When a very Drnaso-like white man does appear partway through, it’s his boring, privileged mediocrity that renders him an anomaly amidst an otherwise diverse and much more interesting cast of characters.

The narrative is also striking in the way it eschews neat resolutions for messy realism. The narrator gets ghosted by a prospective love interest following a tentatively positive date (we never do find out what happened there). She misinterprets the friendly intimacy of her best friend, and the ensuing awkwardness is palpable. She struggles with every creator’s dilemma: how many rejections do you endure before you pack it in and return to the drudgery of a desk job?

Small dramas, perhaps, but it is her tenacity in stringing along the necessities of daily life in between them that resonates: no matter how many personal and professional rejections one faces, we must still cook dinner, shop for groceries, feed the cat. These mundane realities of daily life are often omitted from memoir and fiction alike, and it is refreshing to have them depicted so ardently in Som’s narrative, where they take centre stage.

But that’s how it is, isn’t it? Our personal and professional triumphs are the exception, and those boring dinners at home after a day of drudgery are the norm, are they not? Seeing how protagonists traverse the quotidian offers a different type of insight into their character.

In its concentration on the everyday, Som’s comic is reminiscent of Sunday newspaper strips of yore; her succinct style would have fit the standard well. But in lieu of the white patriarchal family, Som’s narratives centre the queer folk of colour so often omitted from Sunday strips. She is not the first to do this, of course. But there is an endearing and compelling quality to this memoir.

(courtesy of Street Noise Books)

Despite its dwelling on the everyday, Som’s graphic memoir is methodologically innovative as well. Som relates her memories through the form of Anjali, a cisgender Bengali-American woman. Som explains only at the beginning and end of the book the composite nature of her protagonist, and the author’s own gender transition at the age of 50. Her evolving sense of gender identity was in many ways impacted by her presentation of the self in her graphic diary, she explains.

“Loath to draw myself … I substituted Anjali, a cisgender Bengali-American woman in place of yours truly in these recollections,” Som explains. “I realize, in retrospect, that I had resorted to this substitution for another reason: because – well, ’cause Mademoiselle Anjali, c’est moi. Or at least, she is who I thought I could be.”

Partway through, the narrative is joined by Titania, a trans woman and prospective love interest. In her inclusion the reader is offered yet another sliver of the author’s identity and experience. It’s exciting to see all these shards of the author’s evolving identity exploring their own roles in the broader tapestry of the narrative, engaging with each other in both positive and negative ways. (As parts of our personality are wont to do, aren’t they?)

Witnessing them engage in real life offers a vibrant insight into the experience of being that the author conveys. It’s a method that is both more complex and in some ways superior to the chronological presentation of self in first-person, which is more commonly employed in memoir. It also serves an important function in reminding the reader that no memoir comes from a static persona, and sometimes the process of writing the self can be catalytic to one’s experience of living the self.

(courtesy of Street Noise Books)

This is an exciting reminder that memoirs can be innovative and creative too. How does one represent the self in memoir? Which forms of self-presentation and experiential narratives do we convey on the page? If we create seemingly fictive characters to represent us in a story of the self, who is to say those ostensible fictions are not, in fact, a more accurate presentation of reality than the images compiled from photos and other people’s memories which are generically used to construct history? Are there more complex, fictive vehicles that can be used to better convey the essence of one’s story?

In the case of Spellbound, Som did not need to hew to other people’s standards and recollections in order to convey the essence of her life, her ideas, her struggles. Instead, she deploys creative flourish to present herself in a manner more fundamentally authentic to her story and identity. Som calls it a “displaced memoir”: “Anjali began as a substitute but she’s become her own,” she writes, as the narrator and her creation jest and joust for centre space in the book’s final pages, identities slowly merging as they occupy the same panels.

So many memoirs – especially those presented in graphic form – go to such painful efforts to cling to the tediously objective that they lose the spirit of their subject matter, resulting in sterile and aimless strings of facts rather than authentic stories. There are lessons here about the importance of creativity in memoir, and about the agency we possess in narrating our life stories. The book also serves as a reminder that trans memoirs need not hinge on transition narratives, or at least not on the ones we are used to seeing.

Readers may find Spellbound an elusive read at first, but it grows on the perceptive reader in a delightful way — and not only because of the devastatingly cute presence of the narrator’s cat, Ampersand, throughout the book. If memoirs are meant to reflect the essence not just of a single life, but of the times in which we live, we require less self-absorbed white male dramas, and more authentically-paced, richly diverse graphic memoirs like Spellbound.

(courtesy of Street Noise Books)